This week, we welcome to the blog Dimple D’Cruz, Marketing and Communications Assistant at South Asian Arts-uk (SAA-uk). Taking you on a unique tour of Leeds, she tells you all about the work that SAA-uk do around the city, all the while uncovering hidden histories that illuminate the overlooked presence of South Asian communities in Leeds.

A stroll past the legendary Leeds Corn Exchange has bound to have made your travel route at one time or another. And so the chances you have walked by a 32ft tall giant that inhabits the wall a stone’s throw away is more likely than not.

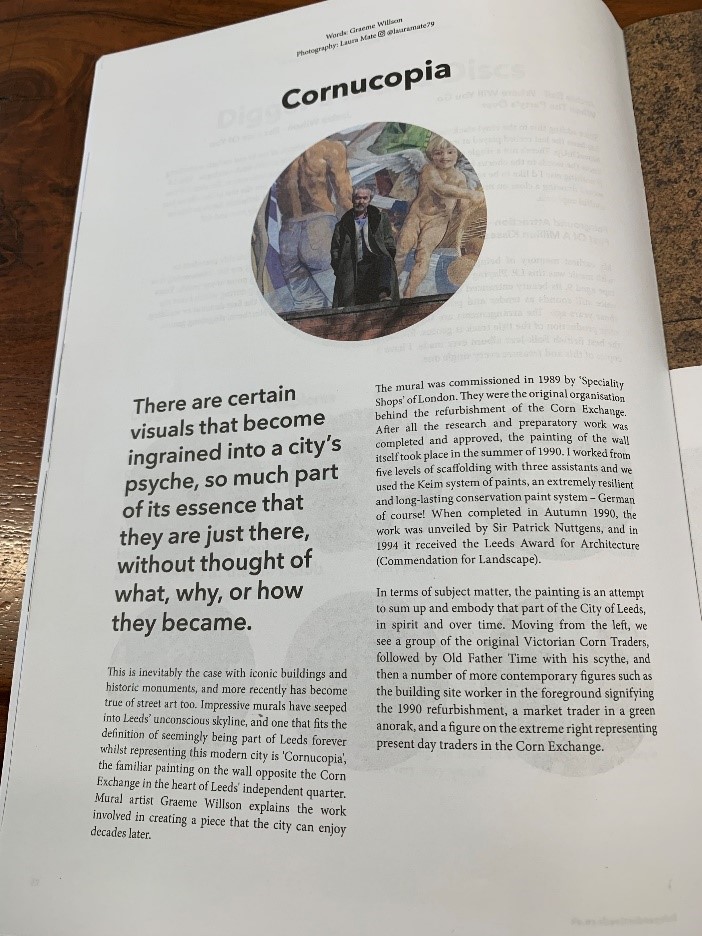

The Cornucopia mural, as it is better known, has cast its watchful gaze down on Leeds for over 30 years, though it radiates an omniscience that feels as though it is as old as the city itself.

Stretching across the skyline, time all but dissolves as you watch past, present, and future fascinatingly all meet within the painting. From top-hatted corn traders of the Victorian era to the more fashionable dungarees adorned by a female figure representing contemporary traders at the Corn Exchange, the mural pays homage to the memory of those who have built this city and to future generations that will continue to carve its legacy.

Gracefully taking her place at the heart of the image, surrounded by the forefathers and forerunners of Leeds, is the portrait of a South Asian dancer whose presence adds a poignant dimension to the artwork. Though the South Asian community within Leeds has been so rich and undeniable for so long now, the celebration of the immense contributions they have made to the culture and identity of the city has remained largely invisible. Cornucopia gloriously seemed to challenge that status-quo. Of course, I had to find out more.

For weeks, my quest to uncover the story of the South Asian dancer led me down the path of vague descriptions that omitted her mention entirely, until I was ushered to the archival material housed at Leeds Central Library. Amongst its treasure trove of preserved histories lay a Leeds Independent Life magazine that contained an interview with the mural artist himself, Graeme Wilson.

“The only figure which is a little out of place is the Asian female dancer, who was included because there had originally been talk of an Asian dance centre being based at the Corn Exchange”.

I must admit, a sinking wave of disillusion washed over me when I learnt that what the dancer represented was a far cry from an ode to the overlooked legacies of South Asian communities within the city that I had theorised. And staying true to its slippery disposition with no remorse for my recent disappointment, irony saw to it to cap off my conclusion for answers with a surge of more questions. The one that gnawed at my curiosity most persistently was the question of why the Asian dancer was ever thought to be out of place?

Since the dawn of the 50’s, when the shadow of the World War still loomed overhead, Britain’s economic state was bludgeoned and on the brink of no return. It was time to revive the nation, but with labour shortages running dry, Britain’s future lay with its Commonwealth countries who offered the hope of filling these shoes at a cheap cost. Enamoured by the charming promise of employment and a future with greener pastures of opportunity for their family, thousands of South Asian communities would bid farewell to their motherlands, bounding across to Britain with a suitcase filled with hopes and dreams. Leeds was one of the cities that South Asian communities would choose to call their new home.

Since then, the hands of time have kept on ticking for over 70 years, with each decade giving birth to new histories, generations and memories all made by South Asian communities in Leeds. Surely that was enough to warrant a self-explanatory place on the famed wall, but because these voices are seldom heard, many of us today, as in the past, remain unaware that this history even exists.

Encouragingly, passionate groups within the city are determined to illuminate these historical blind spots, and one such example is the organisation South Asian Arts-uk (SAA-uk). Harnessing the power of the arts, SAA-uk has dedicated its mission to preserving the heirlooms of culture and tradition for South Asian communities in Leeds to hold onto, all the while encouraging people from different walks of life to join in and explore new traditions and experiences.

Since its inception over 25 years ago, SAA-uk has fought to carve a significant space for South Asian people and their stories to emerge from the vaguely visible corner of the public eye and into full-view. This has included taking South Asian culture and arts to monumental landmarks and iconic spaces across Leeds, seamlessly tying the rich histories of this community to the wider history of the city in a poetic reminder of how the two are interwoven.

From the countless examples I could recount, one that stands out as particularly powerful was SAA-uk and Alchemy Anew’s collaborative project Sacred Sounds.

A grainy picture that immortalised a day in 1915 planted the seed for this project. Cross-legged and seated in a humble French barn, Sikh soldiers of the First World War are seen clutching onto their faith as they perform kirtan (devotional music) thousands of miles away from home. It was bittersweet, as while the image preserved a sliver of the legacy of these Sikh soldiers that fought in the great war, it also illuminated how the stories of 1.5 million other South Asian soldiers who marched Britain to freedom had gone untold.

A powerfully enduring mission was undertaken to excavate hidden histories which included unseen photographs and letters exchanged between Sikh soldiers and their loved ones back home in Punjab.

These mementos were brought to the forefront as the project toured across the North, including venues such as The Royal Armouries Museum and Howard Assembly Room. Each performance infused life back into these legacies which lay dormant for so long using the power of poetry and haunting folk music that evoked the sorrow, longing, and hope that the soldiers endured.

Sacred Sounds would mark the first meeting with this side of World War history for many including myself, and now I was here, what more could I find?

It just happened to be right under my nose, inscribed upon the Leeds University war memorial, the name Jogendra Sen. Born in Bengal in 1887, Jogendra would make the journey halfway across the world to Leeds where he studied engineering at the University in 1910. An enviable intelligence and a lovable disposition were said to be few of the characteristics that defined Jogendra’s essence, but his heroism is what is remembered so vividly. In 1914, when war broke out, Jogendra applied to serve as an officer in the British Army, though prejudice and the colour bar stood in his way. Undeterred and no less eager to serve Britain, Jogendra was one of the first men to volunteer to join the Leeds Pals Battalion, taking on the rank of Private. Jogendra would lose his life fighting for this country, but fortunately his legacy lives on in the city through the poignant memorial that reminds us of his sacrifice.

It is amazing to comprehend just how many of the buildings and streets we absent-mindedly pass by in the city hold the stories of an earlier generation of South Asian people in Leeds who, like Jogendra, paved the way for the bright future we see today. Sadly, most of their names were never acknowledged.

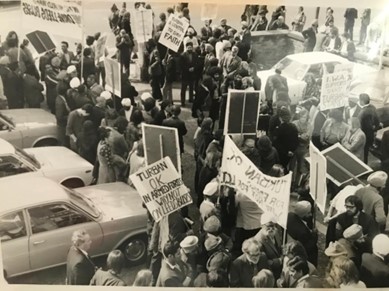

In a conversation with Leeds native Prishant Kaur Jutlla, she walks me down her family’s memory lane. Leeds University makes its unmistakable appearance, yet this time it stands in the light of the 70’s, surrounded by impassioned crowds and dozens of placards. Protest was in the air.

She tells me the story of how her grandfather Kewal Singh Rehal would stand tall amid a sea of change seekers outside the University, who for over six months championed the right for Sikh bus drivers to wear their turbans to work. It was a movement that until now was shrouded from my knowledge. Intent on learning more, I sifted through countless articles and digital archives, yet my efforts generated not a trace of evidence documenting this powerful moment in time. Fortunately, Prishant’s family held onto photographs taken during the protests. This, along with their memories, bear witness to it happening.

When he first undertook his employment as a bus drive in the 1960’s, Kewal was forced to arrive clean shaven and turban free daily to work, but, after a long decade, he would resist.

Arriving one morning to work at the long-gone Vicar Lane Bus station, Kewal’s unexpected donning of his turban was met with a flurry of confusion, but his boss, believing it was a religious holiday and a solitary incident, said nothing. Kewal completed his first bus route of that day, then his second, but after the third, he was confronted by his bosses. When Kewal explained that the turban is a symbol of his faith and he was going to be wearing it from now on, he was immediately dismissed along with the other drivers who wore their turbans. Seeking the guidance from the religious leaders at the Sikh temple, they were advised to keep going into work every day, wearing their turbans and resuming their work as normal, but as I am sure you can guess, they were sent home each and every time.

Disappointingly, the pleas to express their religion and identity freely would fall on closed ears. It was time to make a bigger noise, and so a strike was organised. The courage and vigour of the protestors message resounded across the country, with people from all across the nation lending their voice in support. Unwavering perseverance would at long last prevail; the strikers won the right to wear their turbans in a glorious victory for the South Asian community.

When pivotal stories such as this are so deeply ingrained into the history and development of the city, why is it that they feel impossible to find?

In an effort to recover the long-lost voices of Leeds as part of the ‘Overlooked’ exhibition at Leeds City Museum, volunteers that curated this project explored the mass exploitation that colonial workers faced at the hands of the British Empire. In the process of amplifying these stories, Jordan Keighley, youth engagement curator at the museum, reflected on the immense challenges that were faced along the way, offering an eye-opening explanation to my question.

“Leeds owes a lot to the exploitation of colonial workers, yet there is an absence of their voice in the city’s history. It soon became clear how difficult it would be to represent these voices, with searches of local archives and collections databases yielding almost zero results. This is a common experience for those seeking to unearth histories of minority groups. The volunteers started to think outside the box. Instead of searching for people they began to look at records of trade, particularly the trade of wagons and locomotives made in Leeds. Here the anonymity of colonial workers became strikingly apparent. The volunteers noticed an abundance of photographs depicting colonial workers, however, the captions reveal that these photographs are intended to highlight products rather than identifying the workers. They are not even the subject of the photos that have preserved them; their identities were not deemed worthy of recording”.

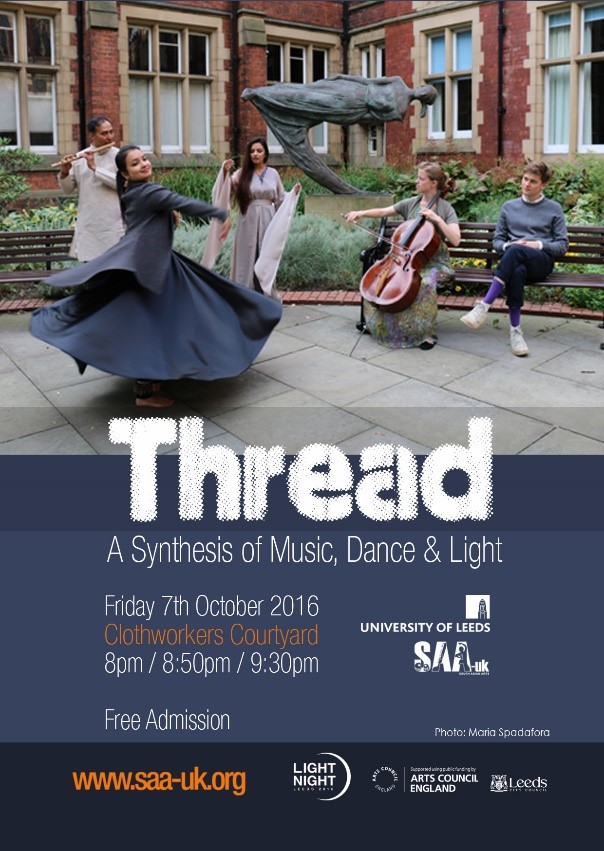

This conversation prompted me to reflect upon a project entitled ‘Thread’ that SAA-uk had undertaken in 2016 as the city took part in celebrating the Yorkshire Year of Textiles. While South Asian communities have contributed so much to the grand textile tradition that for a long time had been tied to the city’s abundance, their stories seem to reside in footnotes, if at all. ‘Thread’ sought to patch up the gaping hole in this history through an evocative performance of sound, light, and dance which artistically captured the monotony of work that both western and Asian women endured in mills and factories. To honour their legacy authentically, meticulous research and development commenced, which included paying a visit to the A.W Hainsworth mill to better understand the rhythms of the machinery. These humdrum melodies would provide the soundtrack to working life that many women had no choice but to listen to, and it marks just one example of the lengths that were taken to uncover and understand the stories of these women.

It just so happens that Kewal Singh Rehal’s wife Davinder has her own stories to tell from bygone days spent working in factories across Leeds. The memory of the Berwin factory comes to her most clearly, where she recalls working alongside at least 70 other South Asian women making thick, woollen winter coats and men’s suits.

Unsurprisingly, the soul sucking theme of monotony comes up in her reflections as she tells of how she would complete hundreds of the same stitching every day. However, another memory breaks through, so lustrously vivid though so much time has passed by. This one is startling different.

There was a hot pipe attached to the wall of the factory where she and the other ladies would place their tiffin boxes on in the morning – by lunch time, their food would be heated up. The dusty factory would be perfumed with the smell of roti and sabjis, a sustaining reminder of their heritage which encouraged them to power through drawling hours of work. Who would imagine that Leeds’ textile industry had roti interwoven in its legacy?

SAA-uk is dedicated to sharing these treasured histories, all the while creating new ones. And come June 21st, at SAA-uk’s flagship event ‘Summer Solstice’, we invite you to the legendary Corn Exchange to be part of a modern history. From day, to dusk, till dawn, musicians from around the world are infusing the city with their beautiful cultural and musical traditions. This includes bringing you the sounds and stories of South Asia as told through mesmerising performances on the santoor, rabab, sarangi and qawwali singing. An effervescent mosaic of people, stories, and creativity will be unveiled, and we hope you can join us to share in the magic.

2 Comments Add yours