The sixth in a newly-regular series exploring books and other items selected from our vast collections. In this entry Librarian Antony Ramm looks at an intriguing work of natural history from the late-18th century…

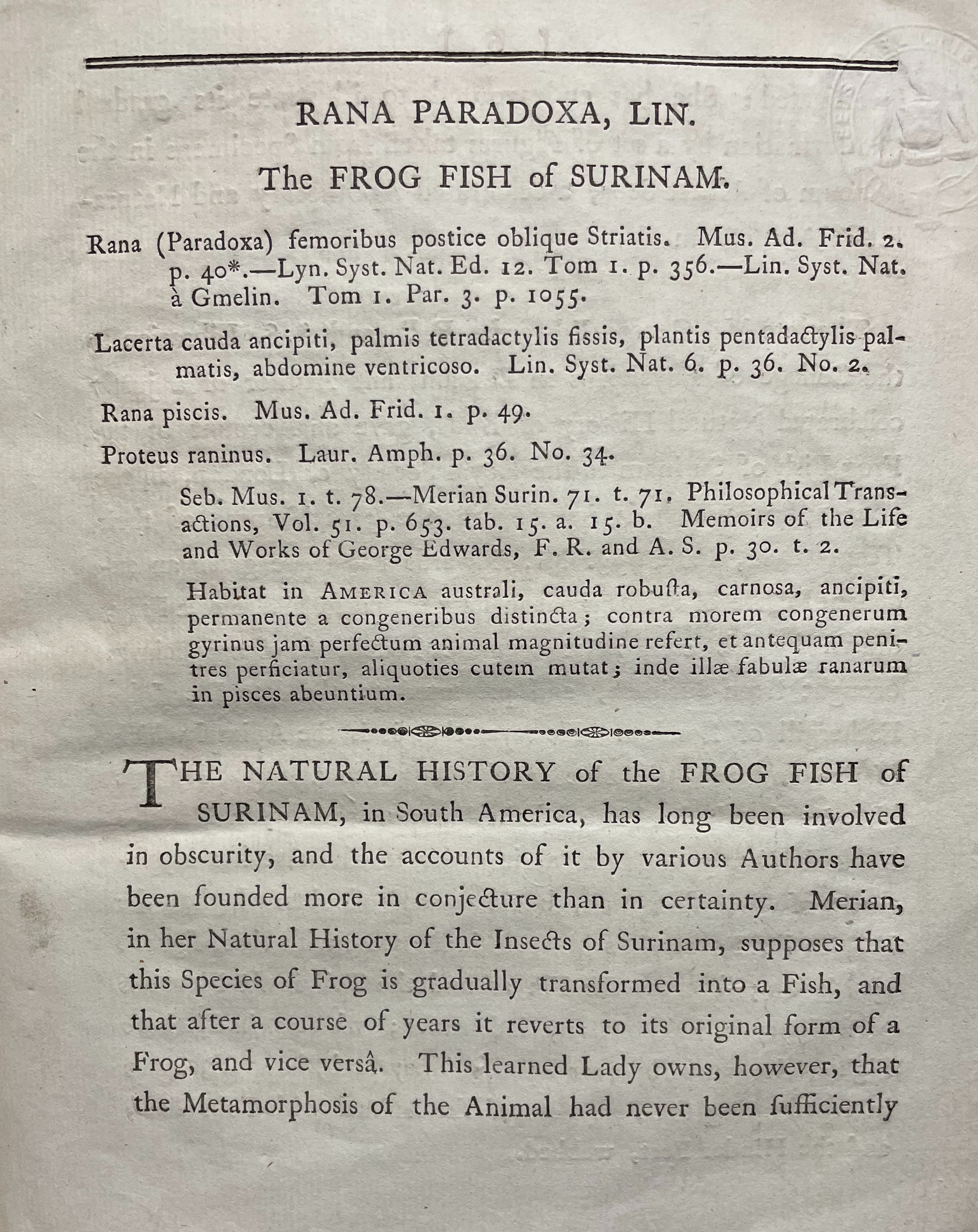

This is an interesting volume, one whose full title according to our catalogue entry is The Natural History of the Frog Fish of the Surinam. I have to confess I’d (shamefully) never even heard of ‘frog fish’, which meant the abbreviated spinal title – The Frog Fish of Surinam – really caught my eye when browsing the Dewey sequence from 596 onwards (see a previous entry in this series for a brief explanation of the methodology behind The Chimney Corner articles).

It’s a surprisingly short volume, that’s the first thing you notice – just eight pages long! I initially thought we must have only a short extract from a larger work, but a quick look at other Library catalogues confirms this is the entirety of the book.

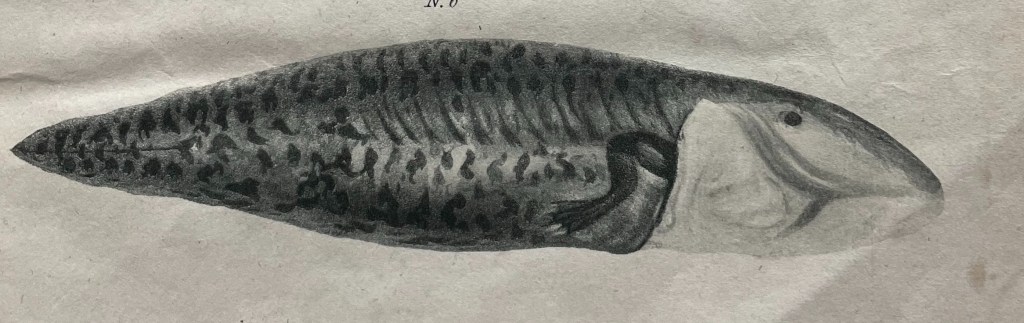

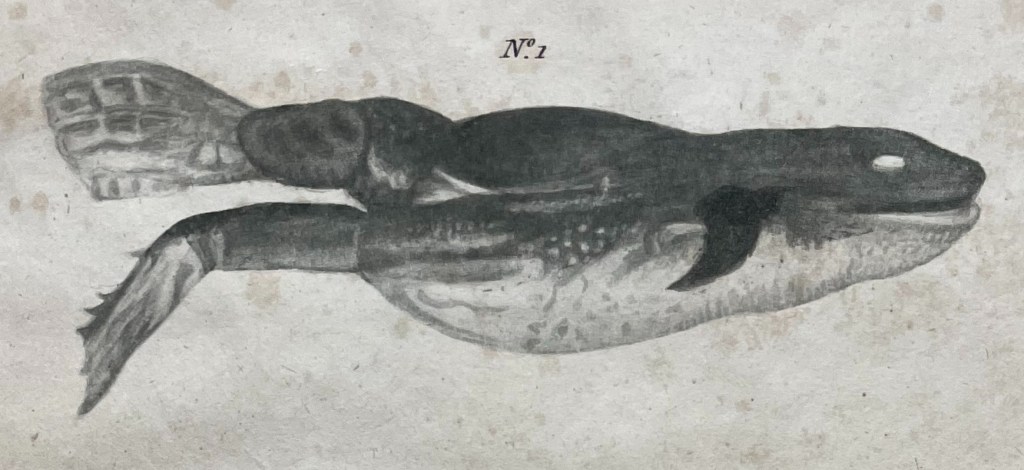

The book has a simple, but effective format: an account of what was known about the Surinamese frog fish at the time of publication in 1796, including references to various authorities with differing opinions as to whether the animal in question changes from a fish to a frog, or the other way around, followed by some charming engravings.

This slim, modest book is an example of Western intellectuals’ pre-Darwinian knowledge of the newly-‘discovered’ natural world of the Global South, at the point where taxonomy, the obsessive urge to catalogue and order information, met the extractive and exploitative practices of mercantile-colonial power: “the scholarly circles of naturalists and collectors, who acquired and studied the plants and insects brought back by traders from around the globe.” (David Brafman and Stephanie Schrader, Insects & Flowers: The Art of Maria Sibylla Merian, 2008. See also footnote 103 on p.36 of S.D. Smith’s Slavery, Family and Gentry Capitalism in the British Atlantic: The World of the Lascelles, 1648-1834 for a description of the relationship between “plantation agriculture and applied natural science” in 17th-century Barbados)

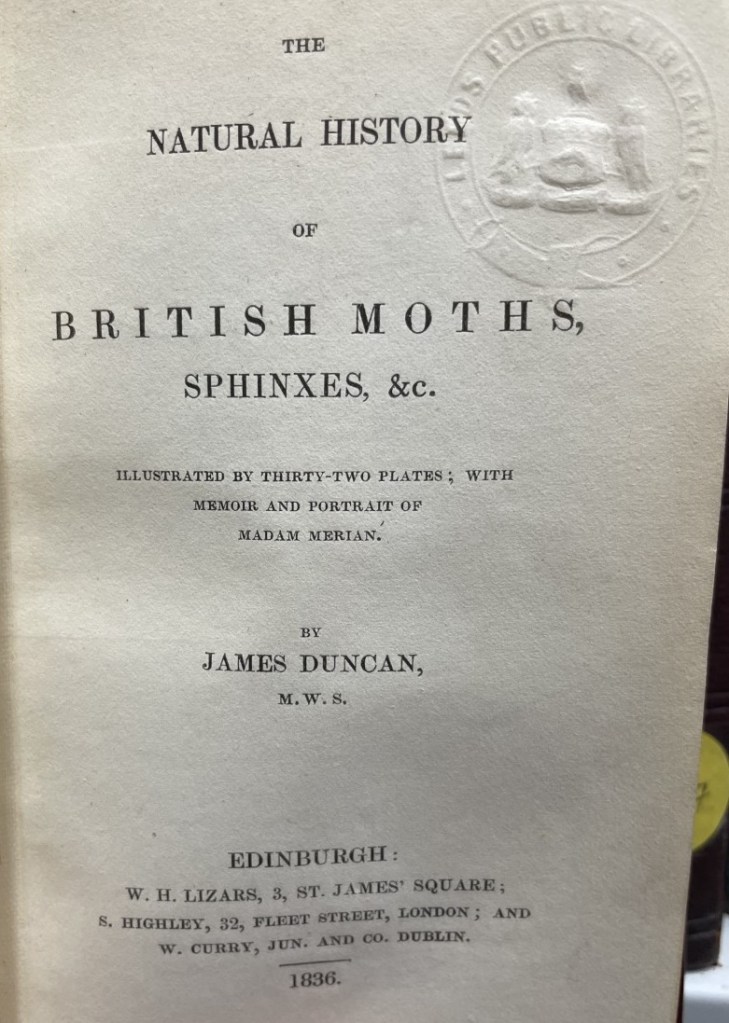

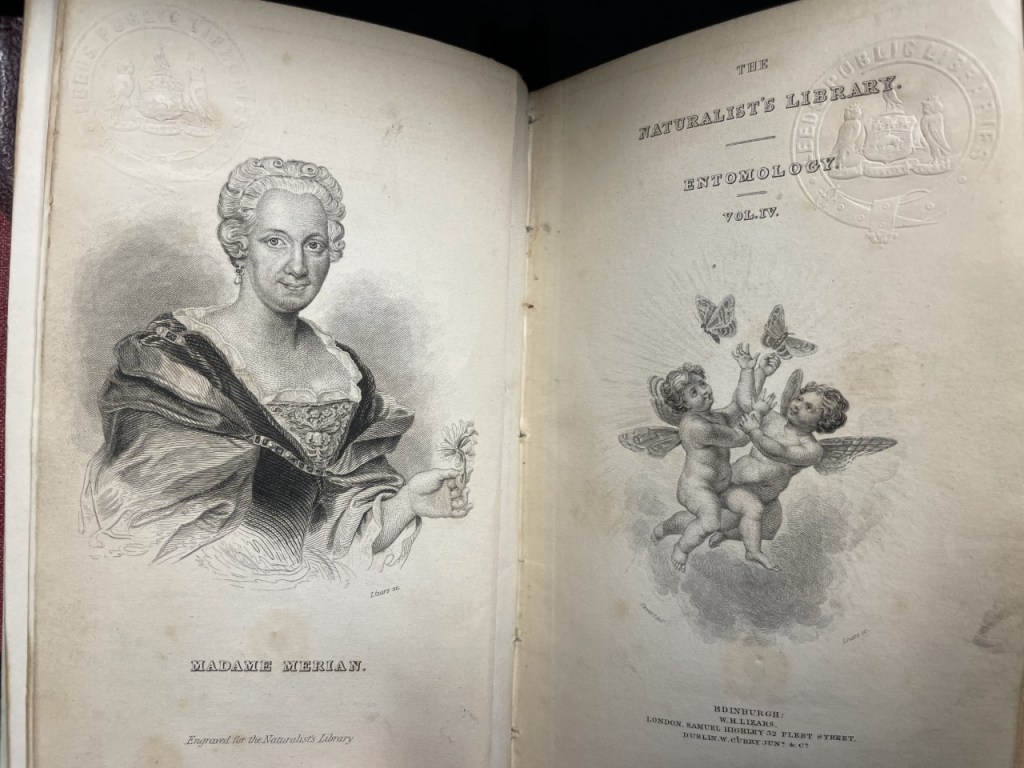

As a (related) aside, one of the authorities referred to in the descriptive section is one ‘Merian’ – almost certainly the pioneering naturalist and artist Maria Sibylla Merian, who conducted significant research in what was then the Dutch colony of Suriname and a short memoir of whom can be seen in a book held by our Information and Research department. Incredibly, that memoir mentions Merian’s illustrations of the same frog-fish! (though in less than complimentary terms)

A modern catalogue of work from Merian’s Surinamese trip is also available in our Art Library, while an excellent children’s book is also available. Merian’s complicated relationships with the indigenous and enslaved peoples of Suriname should be noted at this point.

*****

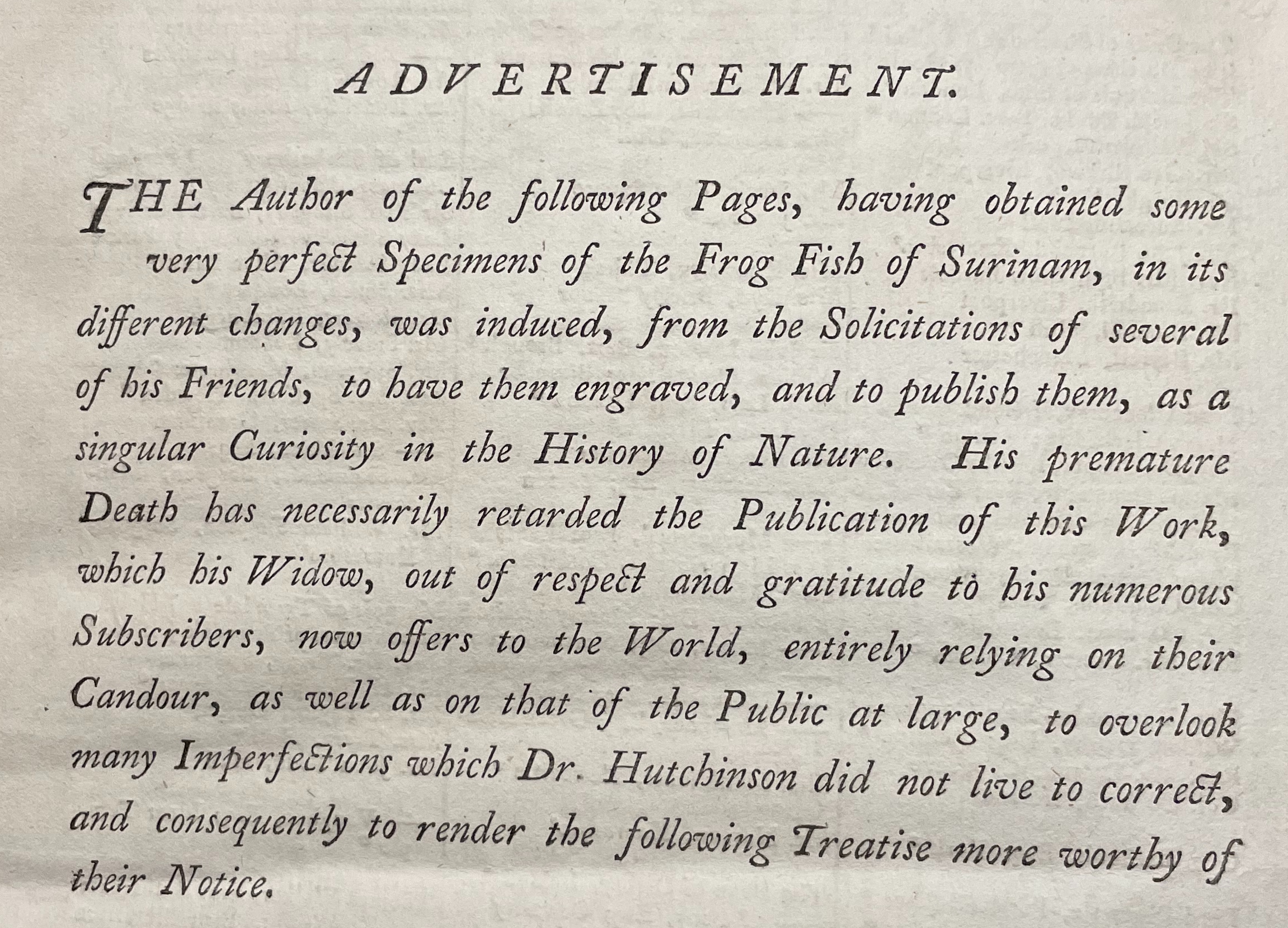

A reason for the book’s short length is given in the preface, which explains that the author, Thomas Hutchinson, died before he could properly gather together his material on the frog fish phenomena, leaving his (sadly unnamed) Widow to publish what had been collected.

So, who was this Thomas Hutchinson? That’s a question I’ve found impossible to answer, with no accurate information available either online or through the usually-reliable biographical sources such as the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. The closest possible match was the clergyman and scholar of that name who lived between 1698 and 1769; no connection between that Hutchinson’s output and natural history can be made, however.

The search for accurate information about ‘our’ Hutchinson is not helped by the existence of a much-more famous (or, indeed, infamous) Thomas Hutchinson in the 18th-century: the governor of Massachusetts Bay in the years leading to the American Revolution. (We’ve even got a book at the Central Library about that Hutchinson, if the fancy takes you. As a former student of American history, I can recommend it.)

*****

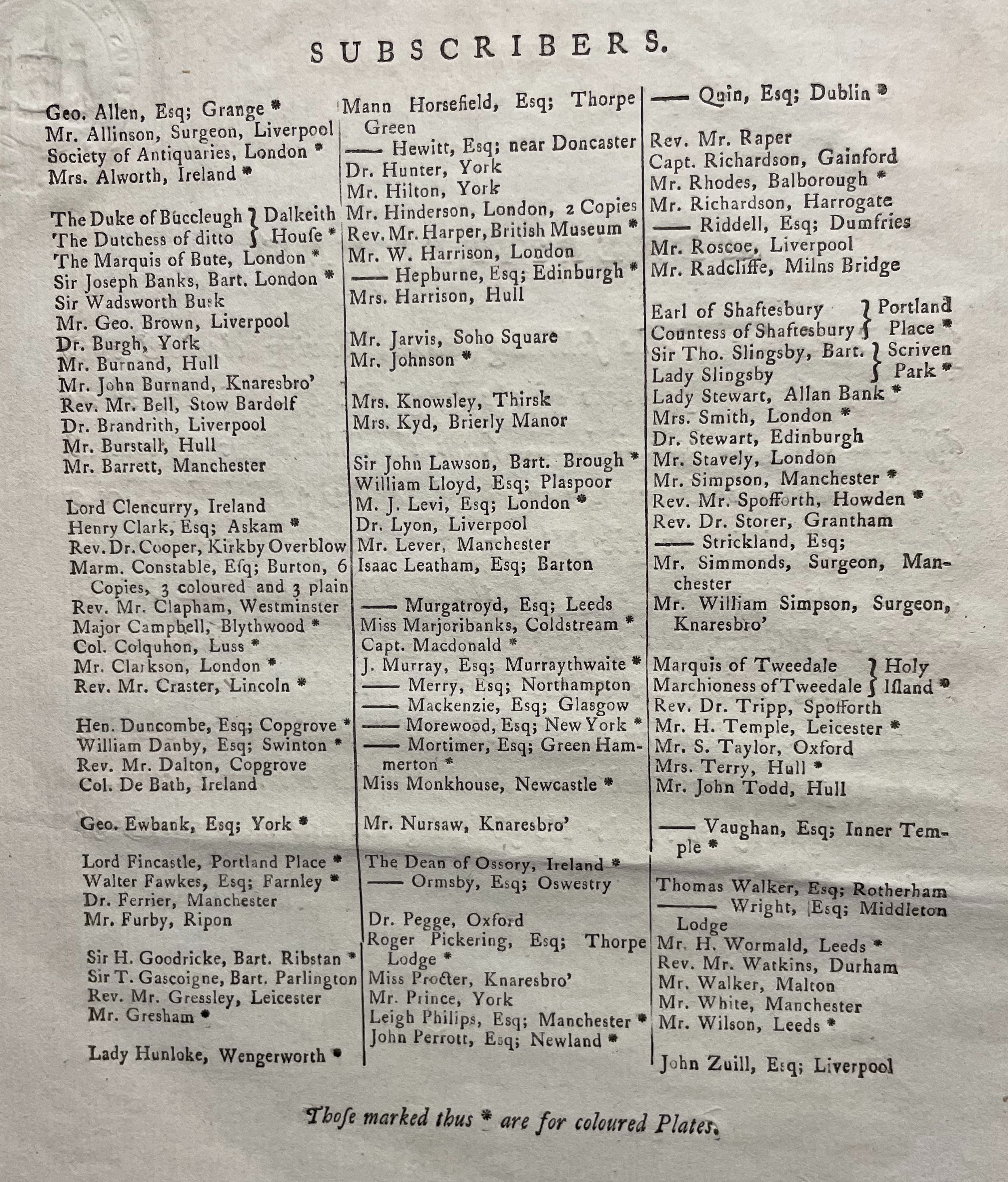

Intriguingly, the book has a couple of Yorkshire connections. Firstly, this edition was sold, we are told on the title page, “by E.Hargrove, at his shops in Knaresbro’ and Harrogate.” Secondly, a list of the book’s subscribers (in whose honour the book was published, “out of respect and gratitude to his [Thomas Hutchinson’s) numerous Subscribers”) includes two Leeds people, alongside some famous names (Sir Joseph Banks!).

Those two Leeds names are: a “Mr. H. Wormald,” and a “Mr. Wilson.” Mr. Wilson has proved impossible to identify, even using contemporaneous trade directories available in our Local and Family History department – there are simply just too many people with the same surname and no way of ruling any individuals in or out of the search.

Mr. H. Wormald, however, proved easier to trace, appearing twice in our trade directory series – once in 1797 and again in 1798.

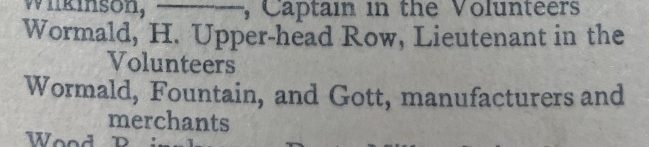

As you can see, that directory entry gives us not only Mr. H. Wormald’s address on the Upper-head Row (now part of The Headrow, of course), but also some indication of his profession or role in late 18th-century Leeds society: Lieutenant in the Volunteers. And that information allows us to trace Wormald’s first name via Emily Hargrave’s article ‘The Early Leeds Volunteers’ in the Publications of the Thoresby Society, XXVIII, Miscellanea IX (1928). There, we find two references to a ‘Henry Wormald’ and a ‘Harry Wormald’ in the role of Lieutenant – presumably the same individual.

Of course, Wormald is a famous name in the annals of Leeds. It was the merchant firm of Wormald and Fountaine which a young Benjamin Gott was apprenticed to in 1780, an event that changed not only the fortunes of that company but perhaps of Leeds itself. That Wormald was one John (or Joseph) Wormald and our Henry (or Harry) seems to have been connected to the same family – the Wormald and Fountaine warehouse was initially on the Upper-head Row and there are multiple references to Henry in Maurice Beresford’s classic East End, West End: The Face of Leeds During Urbanisation, 1684-1842, specifically in connection to Benjamin Gott, who had become a junior partner in Wormald and Fountaine in 1785 and finally took over the whole firm in 1791.

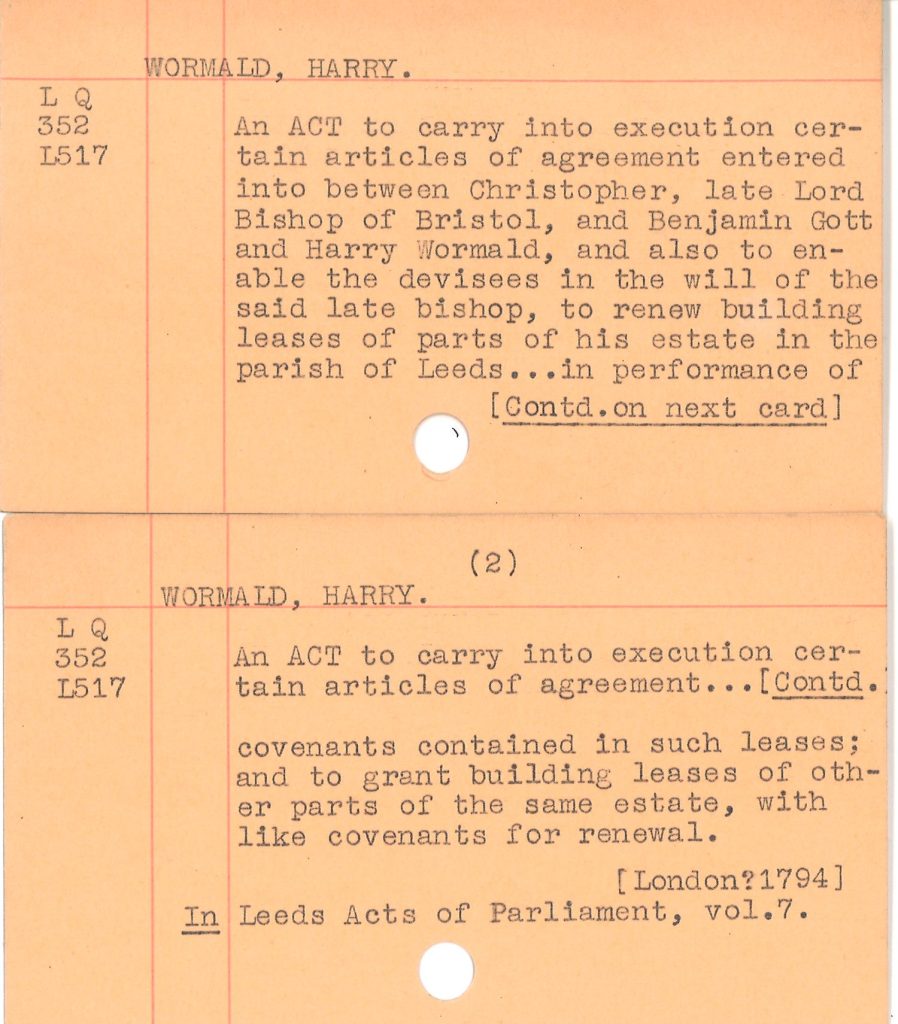

That connection is confirmed both by an 1802 entry in the London Gazette and by a listing in our Local and Family History card catalogue, for an Act of Parliament relating to agreements made between Christopher Wilson, Benjamin Gott and Harry Wormald.

In fact, it was the existence of this card that led to a search in the Beresford book above – that book containing much material about the land in Leeds held by the Wilson family. Henry Wormald must have remained a prominent member of Leeds society; Beresford mentions at one stage that Wormald purchased Denison Hall in 1806 – a fact confirmed on our Leodis archive of historic Leeds images:

I can certainly imagine that property having a significant private library, and our modest book being part of it. Who knows? Perhaps our copy was the same copy once owned by Henry Wormald himself during his time at Denison Hall.

*****

I can’t leave this short-at-first-but-it’s-actually-grown-quite-long article without noting that – apparently, though I’d quite forgotten! – I’d previously used the engravings in this exact same title for a ‘humorous’ attempt at a H.P. Lovecraft spoof in 2016. I only realised this while doing some otherwise futile googling around Thomas Hutchinson. You can find that old article here, and a full list of all the titles used for the images in that previous piece here.

To view The Frog-Fish of Surinam please contact our Library Enquiries team on LibraryEnquiries@leeds.gov.uk or 0113 37 85005. The book belongs to our Information and Research department.

Fascinating piece!