This week we welcome back Library and Digital Assistant Joey Talbot for the second part of his illuminating account of American Civil War veterans buried in Leeds…

In the previous post, I told of how I was put onto the trail of Leeds veterans of the American Civil War after an email from Andrew Hopkinson of Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. But I haven’t yet explained what this organisation is. The SUVCW was founded in 1881 and became the successor organisation to the Grand Army of the Republic, which was a fraternal association of Union veterans, providing comradeship and charitable relief to veterans who had fallen on hard times. Within the SUVCW, the Ensign John Davis Camp 10, established in London in 2016, was the first camp to be established outside of the United States. They have identified 1,155 Union veterans likely to be buried in the UK and have so far located the graves of 543 of these veterans. This includes several more veterans buried in Leeds.

One of the more dramatic stories was that of Alfred Massey Richardson. He was just 18 years old when, together with a friend, he ran away from his home in Manchester to enlist in the U.S. Army. His parents had no idea where he had gone until they received a letter from him, telling them he was now in the 47th New York State Volunteer Infantry.

Distraught, his parents contacted prominent MP John Bright, who took up the case with U.S. authorities. In January 1864, at Bright’s request, Richardson was discharged by Special Order of the Secretary of War. He “objected to leaving the army but was advised to accept his discharge, and did so.” The other Manchester lad who he had run away with was less lucky and died of wounds while in America.

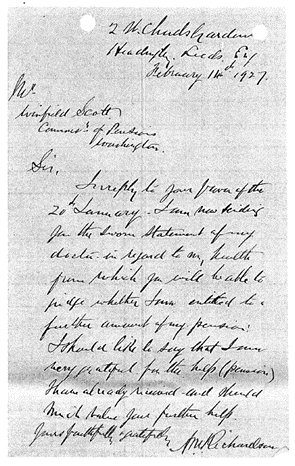

Richardson returned to the UK, and lived for many years in Leeds, working as a colliery supplies agent. In 1922 he successfully applied for a U.S. veteran’s pension, which he continued to receive until his death in 1933.

A more controversial figure was Max Rossvalley, who was born in Germany c.1828 as Mordecai Rosenthal and, according to his own account, emigrated to New Orleans in 1838, changing his Jewish name to a more Anglicised one. In a letter to the Richmond (Virginia) Dispatch for 1st February 1862, he recounts his loyalty to the Confederacy:

As your columns have for months past been the medium of repeated attacks upon my loyalty as a citizen of the Confederate States, and as during my incarceration I was necessarily helpless to repel the charge or vindicate my reputation, now that I have once more regained my liberty, I rely upon your sense of justice to grant me a sufficient space [to] defend myself…. I have resided in New Orleans ever since my first arrival in this country, in the year 1838; I married a native of that city; my children were all born there; and… what property I possess is located there….

My acquaintance with the North is but slight [except for a few weeks] in New York city, while on my way to and from Europe, on a visit to my parents in Germany. … how could I possibly affiliate with the North, or so far forget the thousand and one ties that bind me to the [South]… ls it… reasonable to suppose that… I would sunder the numerous and long-standing friendships I have contracted during a residence of over twenty years at the South, or could so far forget the duty I owed alike to the State and city of my adoption, and, like a base ingrate, allow myself to assist in dragging the Juggernaut car of Lincolnism? I think not.

The true source of the false accusations brought against me, arises from the malice of one or two personal enemies, is jealousy… of the success with which my professional labors have been rewarded by my fellow-citizens of New Orleans, and… of the appointment I hold from Jefferson Davis… I can only say that, if my life be spared, [my fellow-citizens] will have ample opportunity to be convinced, through my deeds, that throughout the length and breadth of our Confederacy there breathes no man who… is… more true or loyal to her than… Your obedient servant, Max Louis Rossvally.

Having volunteered for the Confederates, he was ordered to join the Union Army as a spy. In July 1863, as a Field surgeon at Gettysburg, he had a dramatic encounter with a badly wounded Union soldier, a drummer boy named Charley Coulson whose arm and leg had to be amputated. Coulson prayed for the doctor’s soul then died moments later. This had a deep impact on Rossvalley. He switched sides and re-enlisted as a Surgeon for the Union Army. However, 10 months later he was ordered to appear before the Army Medical Board to give evidence as to his medical qualification. He refused to do so and was dishonourably dismissed.

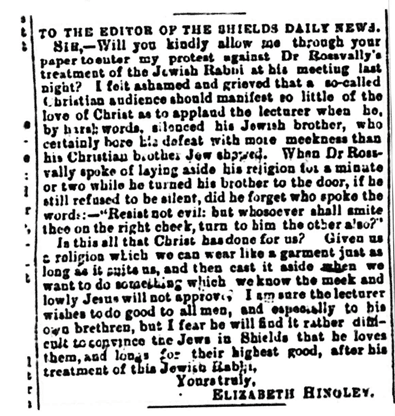

Two children were born to Rossvalley as his wife in New Orleans in 1865 and 1867. But the encounter with Coulson remained on his mind and about ten years later he converted to Christianity. His wife left him the same night, taking their children with her. Rossvalley helped to found the Hebrew-Christian Association of New York and spoke at a meeting of the American Society for the Suppression of the Jews, arguing that the best way to suppress the Jews was to convert them to Christianity. “If this is a free country”, he said, “why can’t we be free of the Jews?” Later, having moved to Leeds, he spent much of his life trying to convert the city’s Jewish population.

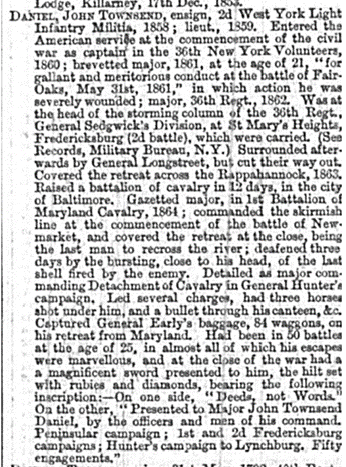

Finally, we have the rather tragic story of John Townsend Daniel. Born in Northamptonshire in 1839, by 1851 he was living in East Ardsley, Leeds with his parents and three siblings. After a brief spell in the West Yorkshire Militia, he enlisted in New York on 13th May 1861 and was commissioned Caption with the 36th New York Volunteer Infantry.

He was severely wounded at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Virginia, in May 1862, became partially disabled as a result and was awarded a 50% disability pension. Yet he remained on active service, including at the Battles of Chantilly in 1862 and Chancellorsville in 1863, and was commissioned Major in July 1863. Indeed, when he submitted a request for leave in January 1865 he stated:

I have been in service during this war for three years and eight months, and have, during that time only had fifteen days leave of absence, and only five since I have been in my present Regiment.

Daniel’s dramatic war record was recounted in the Yorkshire Military List, telling how he “led several charges, had three horses shot under him, and a bullet through his canteen, &c.” It goes on to say how he “had been in 50 battles at the age of 25, in almost all of which his escapes were marvellous, and at the close of the war had a magnificent sword presented to him, the hilt set with rubies and diamonds, bearing the following inscription:- On one side, “Deads, not Words.” On the other, “Presented to Major John Townsend Daniel, by the officers and men of his command. Peninsular campaign ; 1st and 2nd Fredericksburg campaigns ; Hunter’s campaign to Lynchburg. Fifty engagements.”

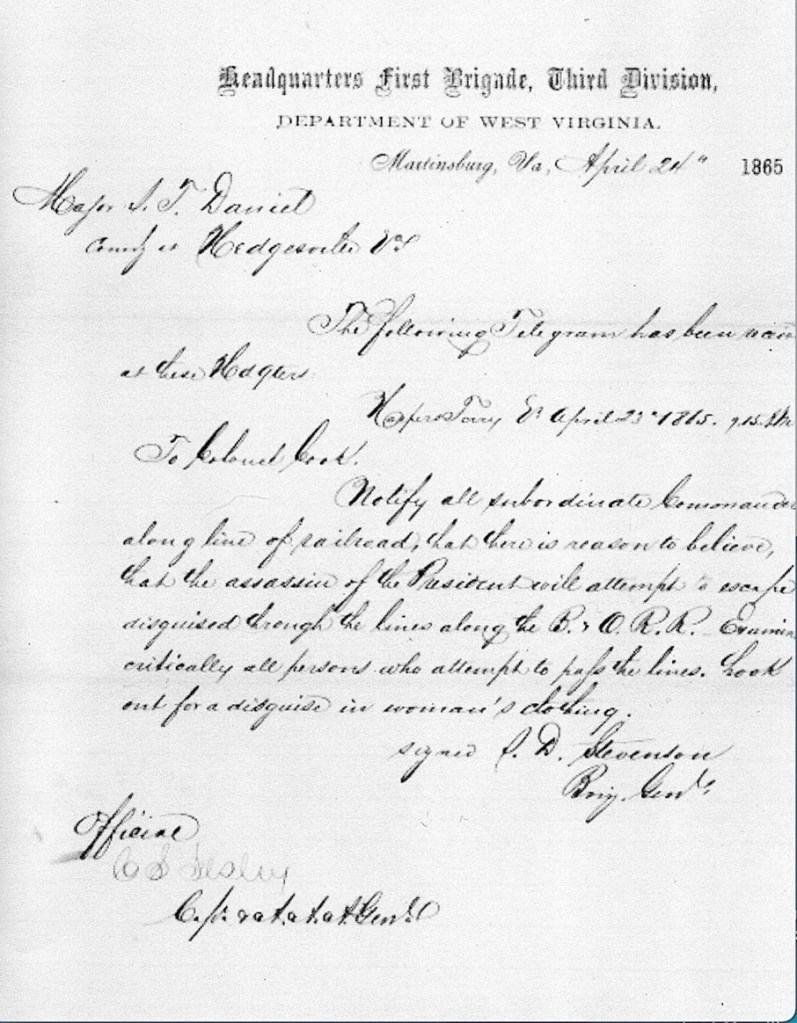

After the war, he was commissioned in the US 7th Cavalry, but soon after this he was accused of forgery, and his appointment expired before the investigation was concluded so he did not join the regiment. This was perhaps fortunate as the entire 7th Cavalry command under General Custer was destroyed by a confederation of Sioux and other Native American tribes at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876.

By 1874, John Townsend Daniel had returned to England and, according to a United States Senate Committee on Pensions report, had been “for some time an inmate of an insane asylum”. He died in Wakefield in March 1877 and is buried in East Ardsley churchyard.

One Comment Add yours