Dr Marta Cobb, from the University of Leeds, has written this article about a fascinating woman writing in the Middle Ages.

We tend to assume that most authors of the Middle Ages were men, when really most authors of the medieval period are simply unknown. So it is possible that there were far more women creating texts than we might think. Moreover, there are women writers that we do know about, such as Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1098-1179), a German abbess who composed books of visionary theology, science, medicine and music! Or Christine de Pisan (1364 – c. 1430), who worked as a professional writer at the court of King Charles VI of France. Christine liked to write about women: one of her most famous works is the Book of the City of Ladies, which depicts the lives of famous women. She also wrote a poem in praise of Joan of Arc. Yet, although I’d like to think that there are lots of medieval female authors only waiting to be discovered, medieval women almost certainly had less access to education and so were less likely to be writers.

One of my favourite medieval authors is Marie de France. We know very little about her for certain. She was born in France (and wrote in French), but she may have lived in England. Her writings were known at the court of Henry II. Marie’s most famous writings are her Lais – a collection of short romantic stories that she claims were originally from Brittany, a region in the north of France. In her introduction to the collection, Marie claims that she heard these stories performed aloud, but that she decided to record them and set them to verse, working on them late at night, so that she can present them to her ‘noble king’ for his enjoyment. Many of these stories involve supernatural elements – hawk knights, magical boats, and werewolves.

To the modern reader, the world of Marie’s lais resembles that of a fairy tale; the usual rules of logic don’t apply. In one of her stories, the knight Guigemar is wounded while hunting. An arrow that he fires at a deer rebounds upon him, giving him a wound that, according to the wounded animal (yes, animals can talk), can only be cured by a woman who is willing to suffer for his love. Instead of returning to his friends, he rides on until he finds a beautiful ship, goes inside, and falls asleep. While he sleeps, the unmanned boat takes him to a strange city where an old husband keeps his young beautiful wife locked away. The knight and lady meet, fall in love, are separated, and eventually find each other again – but not without a few obstacles along the way.

As might be expected from stories of this nature, the lais are sympathetic to lovers, especially to women who have little control over who they are expected to marry. In another story called Yonec, a young wife wishes to have a lover, and a knight who can transform himself into a hawk visits her in her bedroom. The husband eventually discovers her affair and has her lover killed. In the end, however, the child of the adulterous union avenges his father’s death.

Yet, it’s not simply a question of women being allowed to betray their husbands. In another tale called Bisclavret, a wife discovers that her husband is a werewolf and no longer wants to be married to him. She schemes with a lover to steal his clothing, meaning that he cannot regain his human form. At the end of the story, however, she is the one who is punished. Her werewolf husband bites the nose from her face, and the narration assures us that her noselessness will be passed on to her descendants. Her werewolf husband, however, manages to regain his clothes and his human form and lives happily serving the king! It would seem that, for adultery to be justified, the wife must be motivated by true love and the husband must deserve it. In the case of Bisclavret, we are told that the wife did not love the man who helped to betray her husband and, aside from keeping his wolf nature secret, her husband did nothing wrong.

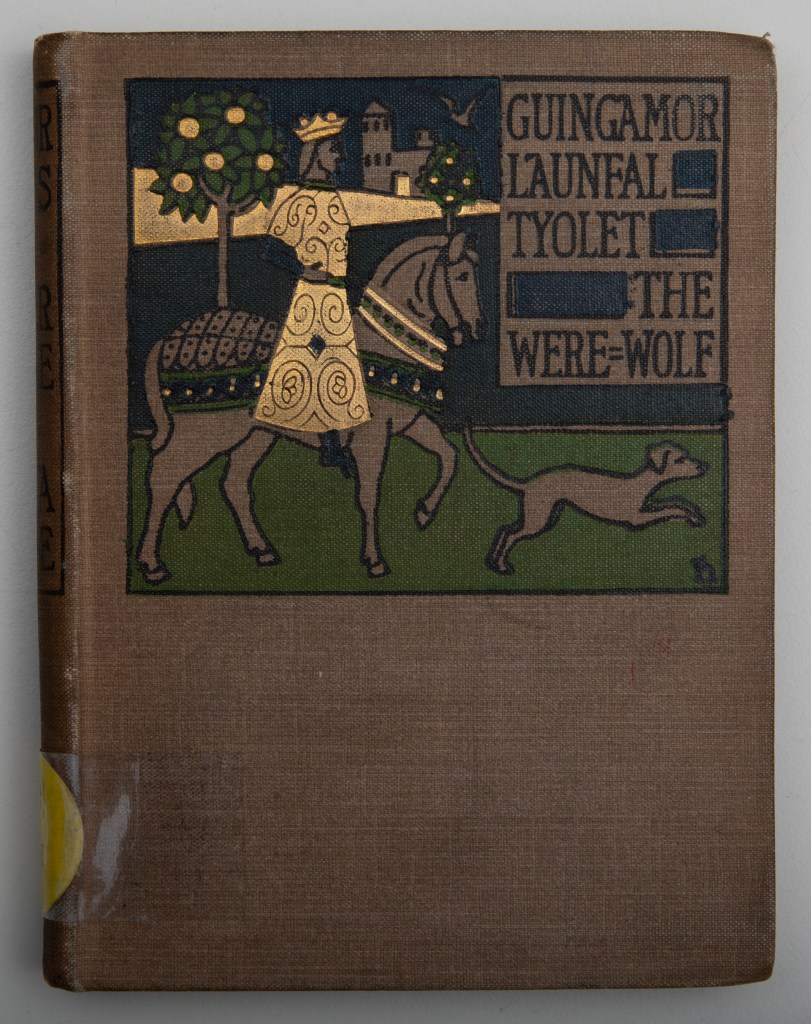

This is just a sampling of Marie’s lais: I highly recommend that you read the rest for yourself and discover not just an introduction to the world of medieval romance but also a unique female voice. One place to begin is in the library, which has a collection of lais by Marie de France (including Bisclavret and Lanval) and other writers. These were assembled and translated by Jessie Laidlay Weston (1850-1928), a medievalist with an interest in Arthurian tales and who, like Marie, was a woman doing scholarly work at a time when it probably wasn’t expected or encouraged. A wider selection of Marie’s lais can also be found online in verse translation by Judy Shoaf.