This week we welcome back Library and Digital Assistant Joey Talbot, who explores the fascinating history of climbing in the Leeds Libraries collections…

During April, we’re holding a display of climbing and mountaineering related materials in the Local and Family History Library, and to tie into that I’m bringing you a little taste of the beginnings of British climbing, the sometimes-dubious personalities involved, and the backstory of one of our key exhibits, the Wasdale Climbing Book.

The valley of Wasdale, in the western reaches of the Lake District, has many claims to fame. It is home to England’s deepest lake and its loftiest summit. Wastwater’s frigid depths reach as much as 79m below Illgill Head’s imposing line of screes, while three miles to the northeast, Scafell Pike sits proud and rocky as the highest peak in the land. But that’s not all. Wasdale is also a key centre for the birth of British climbing. Just beyond the end of the lake, snuggled among the fertile fields of the glacial valley floor is the Wasdale Head Inn, and in the late nineteenth century this establishment became well known as a meeting point for the pioneers who led a ‘golden age’ of early British climbing, developing it for the first time into a distinct and recognisable sport.

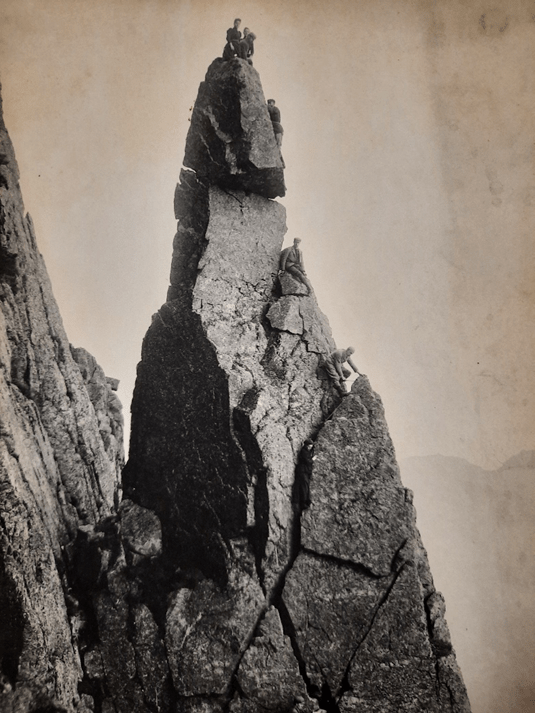

In 1886, the die was cast for the start of this era when Walter Parry Haskett-Smith, a young barrister and Oxford graduate, made the first ascent of the dramatic pinnacle of Napes Needle, the famous rock tower which clings to the slopes of Great Gable, high above Wasdale Head. This achievement was widely seen as marking the birth of climbing as a sport. Before this, climbing in the UK had been seen more as preparation for larger-scale Alpine mountaineering exploits, rather than a worthwhile pursuit in its own right.

Haskett-Smith had first visited the area in 1881, immediately falling in love with its rugged nature. On each of his many subsequent visits, he stayed at the Wasdale Head Inn. He wasn’t alone in this. The Inn became a hotbed of activity, especially during the Easter period each year.

I found a wonderful account of this era when I stayed at the K-Shoes mountaineering hut in Borrowdale on a very wet weekend last November. With the rain pouring down, what better to do than to browse through the hut’s extensive library? In Lehmann Oppenheimer’s 1908 book Heart of Lakeland, he creates a sketch of an Easter day at Wasdale Head, giving nicknames to the key characters who he knew and perhaps climbed with, that in no way obscure their identities.

Oppenheimer’s personalities are a high society mob, the crème-de-la-crème of the climbing scene. We have the Bohemian, “a wild-looking unshaven individual, without collar or tie, and with knickerbockers well torn and patched” (yes, holes in trousers are still a climbing trope today!). Sharp-witted, louche, and independent-minded, he appears to be a combination of the future occultist Aleister Crowley and his close friend Oscar Eckenstein. The other half of this pairing is the Bohemian’s opposite when it comes to his stylish and dainty dress sense. With a silk tasselled cord to fasten his white flannel shirt, he is introduced as the Undergraduate. Meanwhile, Crowley’s rival the Athlete is the Welshman Owen Glynne Jones, or as he sometimes has it, Only Genuine Jones. Fearless when climbing above a drop, but is it just because of his shortsightedness? At Wasdale Head, The Athlete is up to his usual tricks, making the passage of the billiard table leg without touching the floor. Then we have the Photographer, a mash-up of the Abraham brothers, George and Ashley, keen climbers and authors whose Keswick studio produced so many of the historic photographs of this period.

With all these characters competing to put up the most daring new ascents, there was a need to record their exploits. How else could they know whether they were the first to discover a new route, or whether it had been climbed by many others before them? How else could their wondrous achievements be recorded for posterity? The Wasdale Head Hotel visitors’ book had become a repository of information on the development of new climbing routes, but these descriptions were interspersed among unrelated visitor entries. A new solution was needed. And so was born the Wasdale Climbing Book.

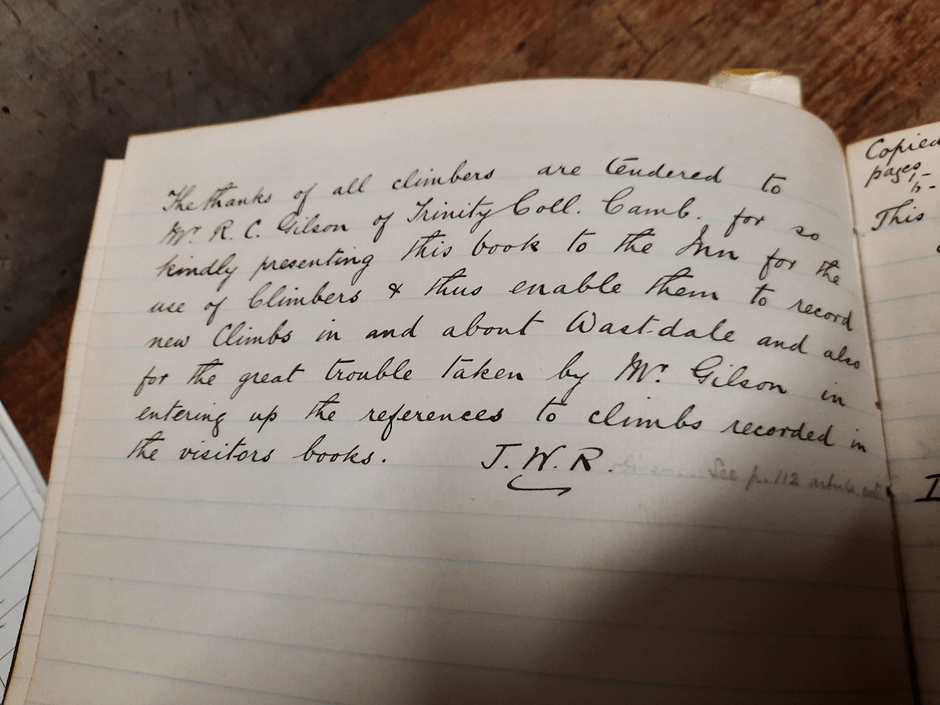

Kept securely at the eponymous inn, the Wasdale Climbing Book was dedicated to the recording of first and second ascents of serious mountain routes. The bound volume was sourced in 1890 by Mr R.C. Gilson of Trinity College Cambridge, who also went to the effort to transcribe references to climbs that had been recorded in the hotel visitors’ book over the last few years. An introductory note by J.W. Robinson thanks Gilson for his troubles.

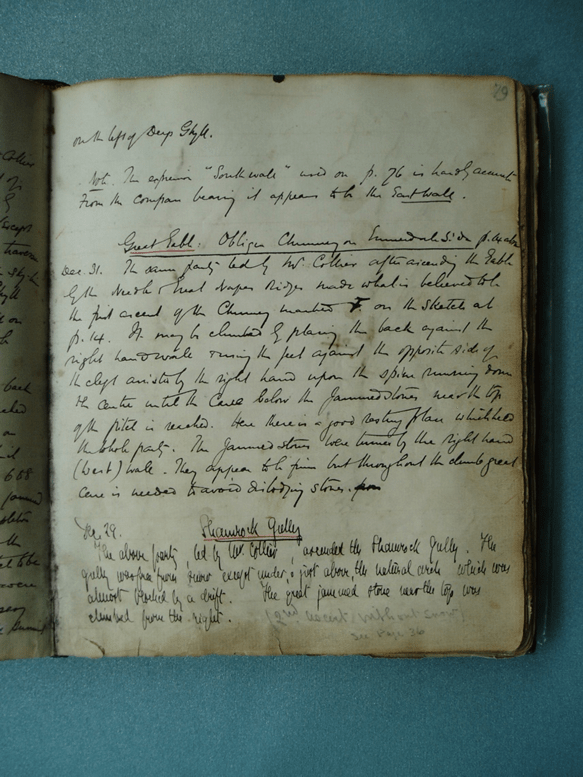

The Climbing Book soon began to fill up with diagrams, photos and accounts of the many new climbs being developed in the Wasdale area. Among the early entries are a series of in-depth accounts of climbs on Moss Ghyll on Scafell: from its first ascent by Collie, Hastings & Robinson on Boxing Day 1892, during which the Collie used his ice axe to hack out a step in the rock (climbing ethics have changed since then!); to A.M. Marshall’s detailed sketch, eight days later, of the newly developed route; to the wintry conditions of O.G. Jones’ lone ascent on 9th January 1893, when

heavy snow had fallen since the previous ascents of the ghyll, and the climb appeared to be exceedingly difficult. Almost every hold had to be scraped clean of snow; essential precautions rendered the climb of 5 hours duration, and it was not completed till after dark (5.45pm).

But the book wasn’t only being used by those planning their next mountain escapade. A note written by Haskett-Smith on 18th December 1893 asks for help transcribing records to assist with the book he is writing. In 1894, Haskett-Smith published one of the first ever climbing guidebooks, Climbing in the British Isles. The first volume covered England; the second covered Wales and Ireland; a third was planned to cover Scotland but was never published. The book comprised an alphabetical listing of climbing venues, detailing the most promising routes and how to find them. Reflecting the sport’s novelty, the sites that were included varied wildly in their scope, from individual routes on Scafell to entire counties or regions such as Somersetshire (whose fine Mendip crags are bizarrely dismissed).

Some years later, leading 1920s Leeds climber Claud Frankland would own a copy of Climbing in the British Isles, which he thoroughly made his own by adding in extra pages filled with photos, sketches, and descriptions of his latest ascents – this book is on display in our exhibition, and for more of Frankland’s tragic story see my earlier article about him.

Meanwhile, Haskett-Smith’s guidebook became the first of many. In 1897, O.G. Jones released Rock Climbing in the English Lake District, published by George Abraham, which crucially introduced the first set of adjectival grades used to classify the severity of climbs. Starting at Easy, these grades would eventually rise through Moderate, Difficult, Very Difficult, Severe, Very Severe, Hard Very Severe, and finally, Extremely Severe. With some modification, these grades are still in use today as the main classification system for British trad climbing. Unlike numerical grading systems, their descriptive nature makes you feel like you’re really putting the effort in. Especially as there are essentially no climbs that are now graded as Easy!

As for the Wasdale Climbing Book, we can’t ignore the fact that the book didn’t go without controversy. Not all Climbing Book entries related to first or second ascents of serious climbing routes. At times, the book was being used to record fripperies and casual days out, either intentionally or accidentally by hotel guests who mistook it for the regular hotel visitors’ book. Some people were very unhappy about this. In several places, pages that were deemed unworthy of the book were torn out, or entries were scribbled over.

One of the most egregious examples of this was an entry by none other than Aleister Crowley himself. He appears to be aggrieved that the book is being used for trivial purposes, so, “Noticing that quantity as well as quality finds a place in this book” he writes what seems to be a satirical entry about a long day out in the fells, including two hours lying unconscious with the effects of sunstroke. The entry is full of simply worded statements “I did this”, “I did that”, and every “I” has been underlined in heavy ink. A note beneath this paragraph then makes cryptic reference to “the lion annotator” who is also apparently suffering with the effects of sunstroke.

No wonder Crowley wasn’t a popular figure among the mountaineering fraternity. His unpopularity would only increase after his spectacularly unsuccessful Himalayan exploits, during which his actions included (in a very abbreviated form) demanding the whole party sign a declaration giving him complete control of the expedition, refusing to leave his tent to help fellow expedition members who had been caught in an avalanche after they had defied his command, and running off with the remaining expedition funds while the rescue was still in progress. Following this, Crowley went on to become an occultist and self-declared Beast 666, known by some as “the wickedest man in the world.”

Now it’s time for me to make an admission. The book which I have been describing is not, in fact, the original Wasdale Climbing Book. I didn’t immediately realise this. To explain the situation, I’d better tell you how I came to be interested in this book in the first place. It came to my attention following a couple of climbing-related customer enquiries. Firstly, from a Spanish climber seeking to find the first ever bouldering guide; and secondly, from a Fell and Rock Climbing Club member writing a history of Pillar Rock and its climbing heritage.

A strong candidate for the first ever bouldering guide is the Y-Boulder guide written by Crowley and L.A. Legros. Written in 1898, this details 22 routes on a single boulder near Wasdale, including one unconventional ascent that must be completed feet-first. But this guide wasn’t to be found in the Wasdale Climbing Book, and turned out to have been written in the hotel visitors’ book instead. Perhaps, in the same way that climbing had previously not been seen as a worthwhile sport in its own right, but merely a training ground for Alpine mountaineering, bouldering was not seen as sufficiently important to be entered into the Climbing Book.

While investigating this, I realised that the Fell and Rock Climbing Club had their own version of the Wasdale Climbing Book, held at the County Archives in Kendal, which was said to be the original. The FRCC kindly sent me images of this book, and from these it was clear that their book was indeed the original.

The story goes as follows: the original book was kept at the Wasdale Head Inn, but it was in regular use and people began to worry that it could be lost or damaged beyond repair. To prevent the loss of irreplaceable climbing history, copies were made of this book. It’s not clear exactly how many copies were made, but they were made on more than one occasion. The incredible thing about the copy we now have here in Leeds is that not only is it handwritten, but the author has gone to great lengths to imitate the different styles of handwriting that are found in the original book.

Our book was created in late 1898 and was almost certainly written by George T Lowe. Lowe was the founder and first President of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club. He was also an artist who went on to become a founding member of the Fylingdales group of artists. He had both a climbing background and the artistic talent required to skilfully reproduce the writing of many different hands, plus numerous sketches and diagrams. The book was eventually donated to Leeds Libraries as part of the G T Lowe bequest, and is one of numerous items we have acquired from members of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club.

The realisation that the Leeds book is a copy explains various odd features of this book. For example, the Crowley ‘sunstroke’ entry that I described above has an insert next to it, explaining that it has been “erased as unworthy of the book.” That’s because in the original Climbing Book, it has indeed been erased. There are also some pages which appear in the Leeds copy but have been torn out of the original FRCC book. For example, on p52 we have two poems written by bickering Wasdale Head Inn guests (going by an entry on the previous page they seem to be ‘W.M. and M.A. James, 2 ladies’), one of whom is feeling jaded by the dreadful weather. The poems were crossed out before the page was eventually removed from the original book:

Oh! dull dismal dreary Wastdale

Where wind ne’er blows but in a gale

Thy very lake hemmed in by fells

Exists as deep and dark as hell

Where’er I roam whate’er I see

It strikes no chord of sympathy

But gloomy dreary full of dread

I turn mine eyes to Wastdale Head

There nothing meets my gaze but mist

‘Neath which the gloomy hills exist

And sunk in barren splendour all

The scenery seems devoid of soul.

And

Oh, Bill I’ll give thee some advice

You’ll take it no uncivil

You should not write at poetry more

But go right to the divil.

It is an insert in the Leeds book explaining that “Pages 51 and 52 have been torn out of the book at Wasdale Head”, signed “GL”, which provides the best evidence that the Leeds book was written by George Lowe. While in some ways it’s disappointing to learn that the book we have here is not the original Wasdale Climbing Book, the ability to see charming pages like these that were removed from the original book underscores the value of our copy. The incredible effort that was gone to to create a realistic imitation of the original Climbing Book shows just how important this was understood to be by climbers at the time. Now its existence gives us the chance to peek into the new world they were creating.

Please contact the Local and Family History department of Leeds Central Library if you have any questions or information to add to Joey’s article. You can reach us on 0113 37 86982 or via localandfamilyhistory@leeds.gov.uk

Firstly, thank you for all the excellent emails. I sometimes hesitate to read them because of becoming involved in the information provided, spending more time than I should.

A. Crowley’s fame has faded somewhat but in 1946 I recall a Ouija Board session with about 10-12 people at my home. Crowley fascinated me at the time because he was an INFAMOUS occultist – I was unaware, at 11 years, of his climbing. I must have received all my information about him from the press articles at the time. To me, I imagine, he was as notorious as Byron must have been in his day.