Following Lauren Stead’s article in May, we now welcome MA student Xuan Li for a further exploration of the Central Library’s Spark Collection…

Over the past few months, I’ve had the chance to work on a short-term archive project at Leeds Central Library, exploring the fascinating Spark Collection. This archive is named after Frederick R. Spark—a local journalist, civic leader, philanthropist, and the first Secretary of the Leeds Musical Festivals. He was interested in loads of different things and was really involved in public life, like music, libraries and newspapers. This left a lasting impact on the city.

Today, Spark’s legacy lives on through the 35 volumes of the Spark Collection, which includes documents, manuscripts, and newspaper clippings that offer a rich window into Leeds’ cultural and civic life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The collection is an invaluable resource for understanding how music, media, and social initiatives shaped the identity of Leeds.

Focusing on Volume 26: Leeds Triennial Musical Festival in 1861, 1874, and 1877

The Leeds Triennial Musical Festival was established in 1858 to celebrate the grand opening of Leeds Town Hall and Queen Victoria’s historic visit to the city. Over the following decades, it grew to become one of Britain’s prestigious classical music festivals, playing a key role in shaping Leeds’ cultural identity.

Volume 26 of the Spark Collection focuses on the early decades of the Leeds Triennial Musical Festival and includes materials from the festivals of 1861, 1874, and 1877. These festivals were significant cultural moments in the city’s history, even if not all of them went entirely to plan. For example, the 1861 festival ultimately wasn’t held as planned, but the preparations, press attention, and civic discussions surrounding it still tell us a lot about the city’s musical ambitions at the time. The 1874 and 1877 festivals, by contrast, were both held and well-attended.

My task was to create a spreadsheet index of the Volume 26 to improve access for future researchers and the public. This volume, while neatly bound, lack an online index, which means it has been underused due to limited accessibility. By systematically recording the contents of each page, including type of material, date range, and brief description, I aim to make this unique archive more searchable and useful for historical research. (Get in touch with us if you want to access the Spark Collection spreadsheet).

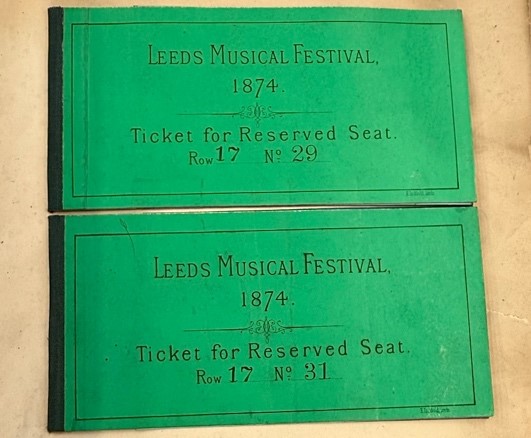

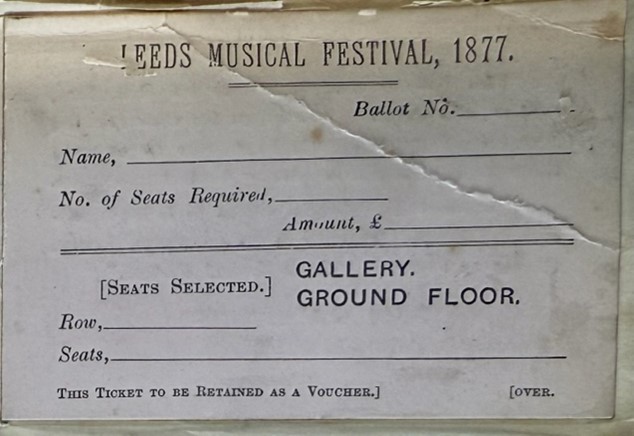

This volume preserves a wide range of material: festival programmes, meeting minutes, press coverage, handwritten notes, and even some tickets. Together, these documents don’t just show what happened, they tell a broader story about Leeds’ ambition, creativity, and civic pride.

Abandonment and Revival: the long and winding road of the Leeds Triennial Musical Festival in early years

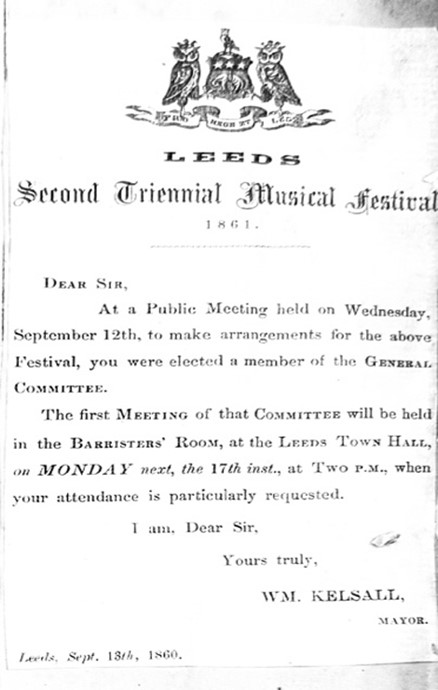

After the first Leeds Musical Festival was successfully held in 1858, preparations for the next festival began in 1860. As shown in the pictures below, Vol. 26 contains various meeting invitations, minutes, and related news reports during the preparation process. These archives provide a vivid picture of the organizational efforts behind the scenes.

However, disputes between different choral societies within Leeds’ musical community became the primary cause of the festival’s eventual cancellation. The conflict is extensively covered in newspaper clippings preserved within the archive, offering a detailed account of the tensions that undermined the preparations. Beyond these reports, various underlying factors contributing to the festival’s abandonment were analysed in articles also included in the collection. Notably, J.W. Atkinson authored a comprehensive article that summarized the reasons behind the decision to abandon the Leeds Musical Festival at that time.

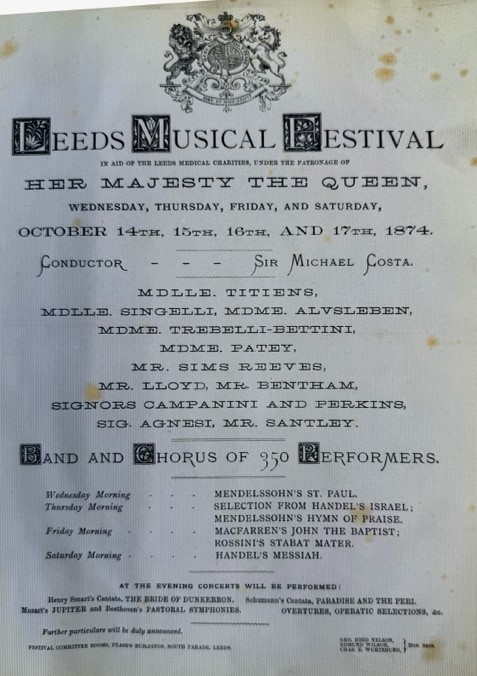

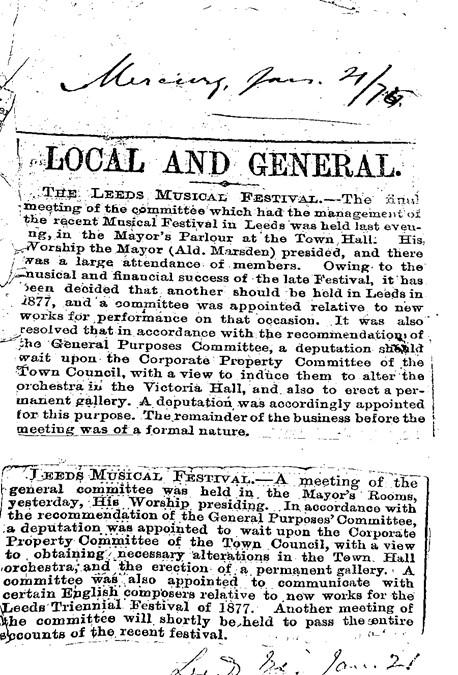

The Leeds Triennial Festival fell silent for a time and was not held again until 1874. Vol. 26 fully records the preparation process of the 1874 festival and shows the extensive communication and concerted efforts of the many people behind the program. Likewise, various reports of the programmes are included. There is no doubt that the 1874 festival was a huge success. According to the press reports included in the archive, its success led directly to the organization of the 1877 festival.

Traces of the Past Left Behind

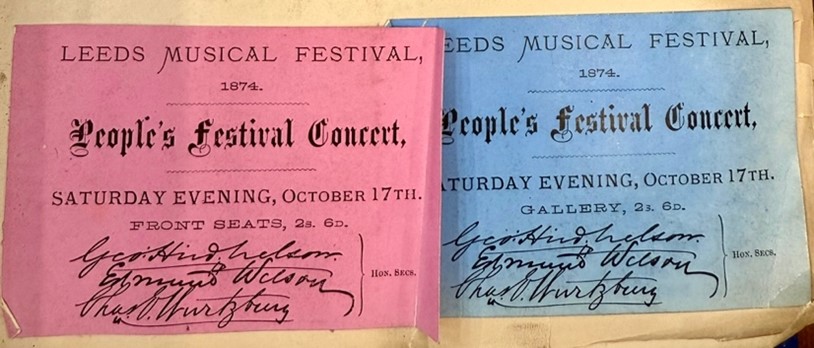

One of the most memorable discoveries I made during my work was a few preserved festival tickets. They are neatly printed, beautifully decorated, and carry great significance. These tangible items connect us to the audiences who filled the concert hall 150 years ago. They remind us that behind every event recorded, there were real people participating, listening, and celebrating. It is these artefacts that bring this archive to life and make history feel more personal.

Reflections and Future Use

Working on the Spark Collection has been a truly enriching experience for me. Each document tells a story, not only about music and performance but about the city’s social and cultural identity. I am hopeful that the spreadsheet index I created will make this treasure trove more accessible and spark further research and public interest.

For anyone passionate about Leeds music history or local heritage, the Spark Collection offers a rare glimpse into a bygone era. I encourage everyone to explore these archives and discover the echoes of Leeds’ vibrant musical past.

For more information on the collection and database, please contact the Local and Family History Department at localandfamilyhistory@leeds.gov.uk or on 0113 37 86982