In connection with the ongoing Unearthed exhibition at Leeds Central Library, here’s a sneaky look at the backstory of a Yorkshire botanist whose passion for plants led him far and wide, touching on the worlds of science and medicine, empire and gardening. We then peek into his connections to one of the biggest scientific breakthroughs of the nineteenth century.

A sickly child, Richard Spruce (1817 – 1893) suffered from bronchial troubles from a young age. He was encouraged to spend time outdoors around his home village of Ganthorpe near Castle Howard, helping to spur on his love of botany. By age 16, he had already recorded over 400 local plant species. He had a deep interest in mosses and liverworts, the smallest and most reclusive of plants, and he was soon publishing papers and describing species that were previously unrecorded in the UK, increasing for example the number of recorded mosses in Teesdale from 4 to 167.

In 1844, Spruce came to the attention of Sir William Hooker, the first director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, whose work also features in the Unearthed exhibition. Hooker recommended him for travel to the Pyrenees, and subsequently, to Amazonia. These voyages were funded by selling thousands of plant specimens to his European subscribers, although given his predilection for tiny mosses, these would have appealed more to plant scientists than to wealthy collectors with gardens designed by landscape gardeners like Humphry Repton, who might have been interested in plants with more dramatic foliage.

Nevertheless, mossy grottoes did have a reputation in Victorian times as places of secrecy and even sexual liberation, allowing space for primal yearnings away from the uprightness of the wealthy Victorian home. Spruce, too, revelled in the beauty of such mossy cirques. He loved these plants for their own sake, not merely for any benefit humans could derive from them:

I like to look on plants as sentient beings… which live and enjoy their lives — which beautify the earth during life, and after death may adorn my herbarium… It is true that the Hepaticae have hardly as yet yielded any substance to man capable of stupefying him, or of forcing his stomach to empty its contents, nor are they good for food; but if man cannot torture them to his uses or abuse, they are infinitely useful where God has placed them, as I hope to live to show; and they are, at the least, useful to, and beautiful in, themselves — surely the primary motive for every individual existence.

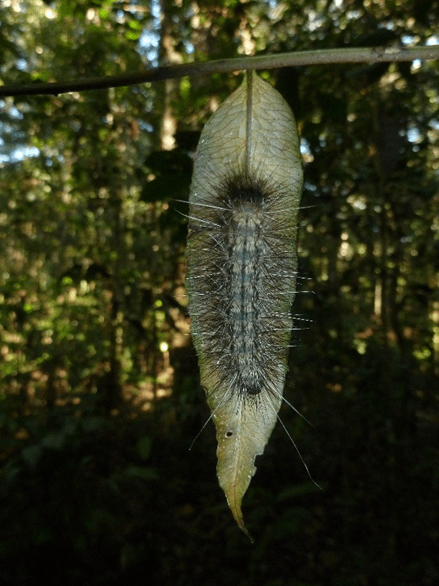

In 1849 Spruce arrived in the Brazilian Amazon on a 15 year expedition, during which he documented 21 Amazonian languages, mapped three previously unexplored rivers, described hundreds of previously unknown plant and fungi species, collected 14,000 herbarium specimens, contracted various illnesses, and even dabbled with psychedelics.

Spruce had great respect for the native peoples he encountered and heavily relied upon during his time in South America, condemning British use of forced labour and describing ‘savagery’ as a response to contact with violent European practises. Recognising the importance of plant cultivation in indigenous cultures, he collected everyday objects like cassava graters, as well as ritual objects. He classified various psychotropic plants and described their indigenous uses, including an account of ayahuasca preparation by the Tukano people of the Rio Uaupés:

I had gone with the full intention of experimenting the caapi on myself, but I had scarcely dispatched one cup of the nauseating beverage, which is but half a dose, when the ruler of the feast—desirous, apparently, that I should taste all his delicacies at once—came up with a woman carrying a large calabash of caxiri (madnidocca beer), of which I must needs take a copious drought, and as I knew the mode of its preparation, it was gulped down with secret loathing. Scarcely I had accomplished this feat when a large cigar, 2 feet long and as thick as the wrist, was lighted and put into my hand, and etiquette demanded that I should take a few whiffs of it—I, who had never in my life smoked a cigar or pipe tobacco. Above all this, I must drink a large cup of palmwine, and it will be readily understood that the effect of such a complex dose was a strong inclination to vomit, which was only overcome by laying down in a hammock.

On behalf of the colonial government of India, Spruce was commissioned in 1859 to gather Cinchona, an Andean tree cultivated for production of quinine, the world’s first anti-malarial drug. Controlling malaria was seen as vital for the success of European colonialism in many tropical countries, but the governments of the recently independent South American states wanted to keep control of this lucrative trade. They had banned the export of Cinchona, which they saw as an act of theft or biopiracy, but the trees were already being exploited close to the point of extinction.

Spruce gathered 100,000 seeds and seedlings of Cinchona, transporting them to the Pacific coast and destroying the remains of his health in the process. But ultimately more important for the medicine’s development was Manuel Incra Mamani, the Peruvian seed collector employed by another Englishman involved in the same enterprise. He had the expertise to identify the most potent varieties of Cinchona and thus was instrumental in enabling successful quinine production outside of South America. But this came at a high personal cost, as he was called a traitor by locals who didn’t want to lose their livelihood, was arrested and died after a police beating.

On return to Yorkshire, Spruce’s health was as poor as his bank balance. The collapse of a Peruvian bank had cost him his life savings and he was so unwell that he couldn’t sit up to work and had to analyse his specimen collections lying down – he joked that he was himself turning into a moss. He spent the last 27 years of his life at Coneysthorpe in Yorkshire, publishing a major work on the Hepaticae of the Amazonian and Andes but leaving much of his other writings uncompleted.

During his Amazonian exploits, Spruce had crossed paths with his friends and fellow naturalists Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Bates. When Wallace was struck with malaria Spruce had helped him, and now his friend returned the favour. Following Spruce’s death in 1893, Wallace posthumously edited Spruce’s Amazonian writings and published them in 1908 as Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and Andes. With a keen eye for popular interest, Wallace printed the detailed botanical sections in smaller font, while emphasising the travelogue sections and topics such as the Amazon’s female warriors.

Now let’s have a brief look at Wallace’s story. Naturalist, geographer, socialist and spiritualist, Alfred Russel Wallace brought understanding of how geographical barriers have caused species to diverge from one another through his breakthroughs in evolutionary theory and biogeography, before distributing many of these species to collectors around the world.

Wallace’s four-year long Amazonian voyage was his first foray investigating the origin of species. He collected thousands of biological specimens, but on return to the UK his ship caught fire in the mid-Atlantic and most of the specimens and field notes were lost. Despite this, Wallace drew on his experiences to write A narrative of travels on the Amazon and Rio Negro, encompassing biology, anthropology and travelogue.

Wallace next travelled to the Malay Archipelago, and it was here, in the throws of a malarial fever that he conceived the idea of evolution by natural selection. He wrote to Charles Darwin, who, unknown to Wallace, had been pondering similar concepts for 20 years without yet daring to publish and risk upsetting the scientific and religious establishment. This was the push Darwin needed, and he presented both of their ideas to the Linnean Society shortly afterwards.