This week we are joined by two guest authors, Lucy M. Evans and Spencer Needs, who write about a little known poet from Leeds – Eliza Craven Green.

Part 1: The Manchester Connection by Lucy M Evans

On 24 March 1842 over forty people assembled at the ancient Sun Inn, Long Millgate, Manchester for a “poetic festival.” All were men although it was rumoured one of poets, Isabella Varley, hid behind a curtain to hear her Love’s Faith recited. Such gatherings of poets, singers and musicians were not uncommon but what made this one special is the little book, published a few months later, that recorded the “literary contributions.” Only a few copies of The Festive Wreath survive: nineteen poets are featured, most were from Lancashire, and only four of them were women.

Some of these poets were famous locally but with two exceptions their works have long since fallen into obscurity. Isabella Varley is still renowned as Mrs Linnaeus Banks, the novelist of The Manchester Man. Out of all of them only Eliza Craven Green has a poem that remains significant in the twenty first century.

It is somehow satisfying that a woman, Eliza Craven Green, wins the crown of The Festive Wreath poets. Yorkshire may also be proud of her for she was Leeds born and bred.

So, which one of Eliza Craven Green’s poems keeps her memory alive when her fellow poets and their works have faded?

Her poem, Ellan Vannin (the Isle of Man in Manx Gaelic) was first published in the Manx Sun in July 1854. It was described as “written for music” and various adaptations followed. This haunting song, as set to music by J. Townsend, was for a long time the unofficial anthem of the Isle of Man and is still much loved and sung today.

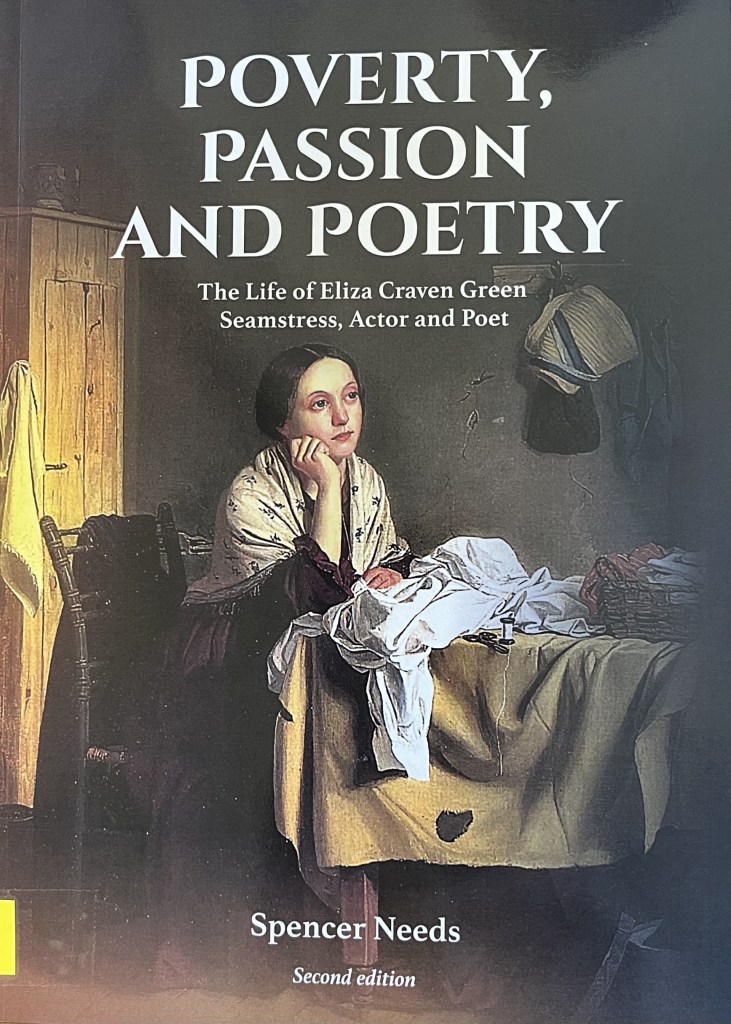

It is a challenge to uncover the details of The Festive Wreath poets. However, in the case of Eliza Craven Green I struck gold. Her moving story is told by Spencer Needs, in Poverty, Passion and Poetry, The Life of Eliza Craven Green, Seamstress, Actor and Poet, published in 2021, second edition 2025, held at Leeds Central Library.

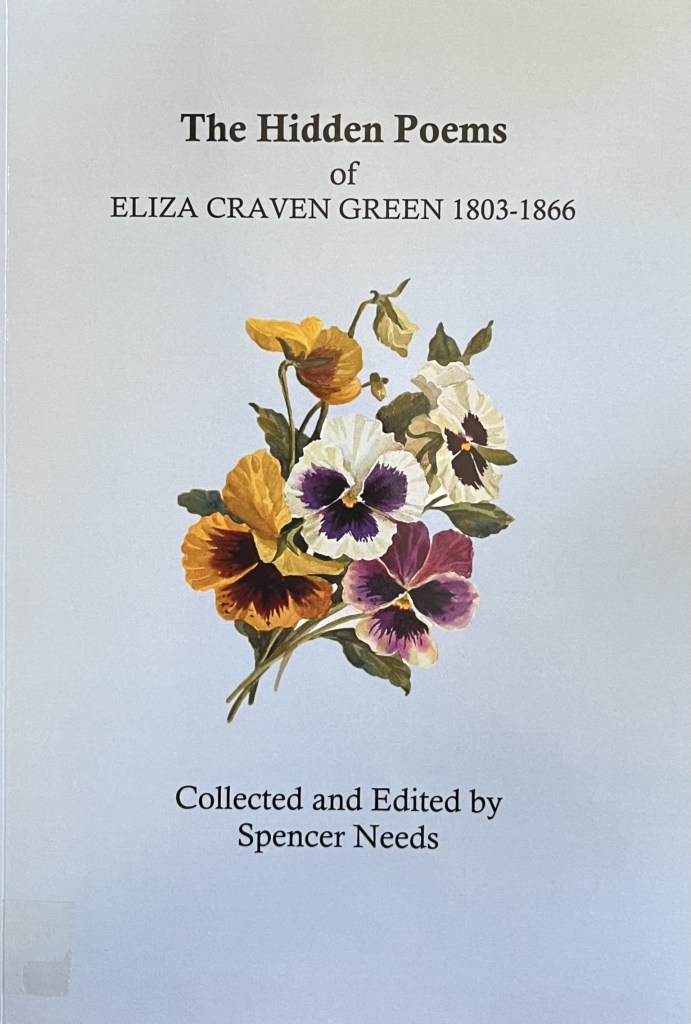

Spencer has subsequently discovered over three hundred more poems, many of which appear in his book The Hidden Poems of Eliza Craven Green 1803-1866, held at Leeds Central Library.

James Waddington was a local poet who died at the early age of 32. Spencer Needs explains the family connection in the following section. Eliza edited and published his poems: a copy of this rare book, Flowers from the Glen: the Poetical Remains of James Waddington of Saltaire, is held at Leeds Central Library.

Other of her works can be found online or as reprints. Spencer Needs is currently collecting her stories and making them available on academia.edu

Now over to Spencer Needs for the story of Eliza Craven Green.

Part 2: The Life of Eliza Craven Green (by Spencer Needs)

I welcome the opportunity to give an account of Eliza’s life but first I must introduce myself as I am also part of the story. Eliza was my great great grandmother on my father’s side. In family history researches I quickly became interested in my great grandfather Henry Hawes Craven. We knew in the family that he had been scenic artist and set designer for Sir Henry Irving a famous actor manager of the Victorian period. It was his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography that led me to his mother Eliza Craven Green. Soon after I found that her poem Ellan Vannin had been sung and recorded by the Bee Gees, who were born in the Isle of Man. It was the haunting rendition of this song by Robin Gibb which inspired me to delve into her life. It is natural to think that in my family there would have been some mementos, letters perhaps or even a photograph of Eliza. However, her name had never cropped in any talk about previous generations, there was simply no trace of her at all.

Faced with a blank sheet of paper, as it were, I turned to the skills of an excellent Yorkshire based genealogist who rapidly provided me with the basic frame work of Eliza’s origins and places where she had lived. It was soon evident from the addresses in courts and yards that Eliza was very poor. It also began to be clear that poor people do not leave a trail of information about their actions, unlike the wealthy and of course criminals. Her entry in the Dictionary of National Biography gave a few clues as to where I might find her work and from these slender leads, I have built up a picture of her life.

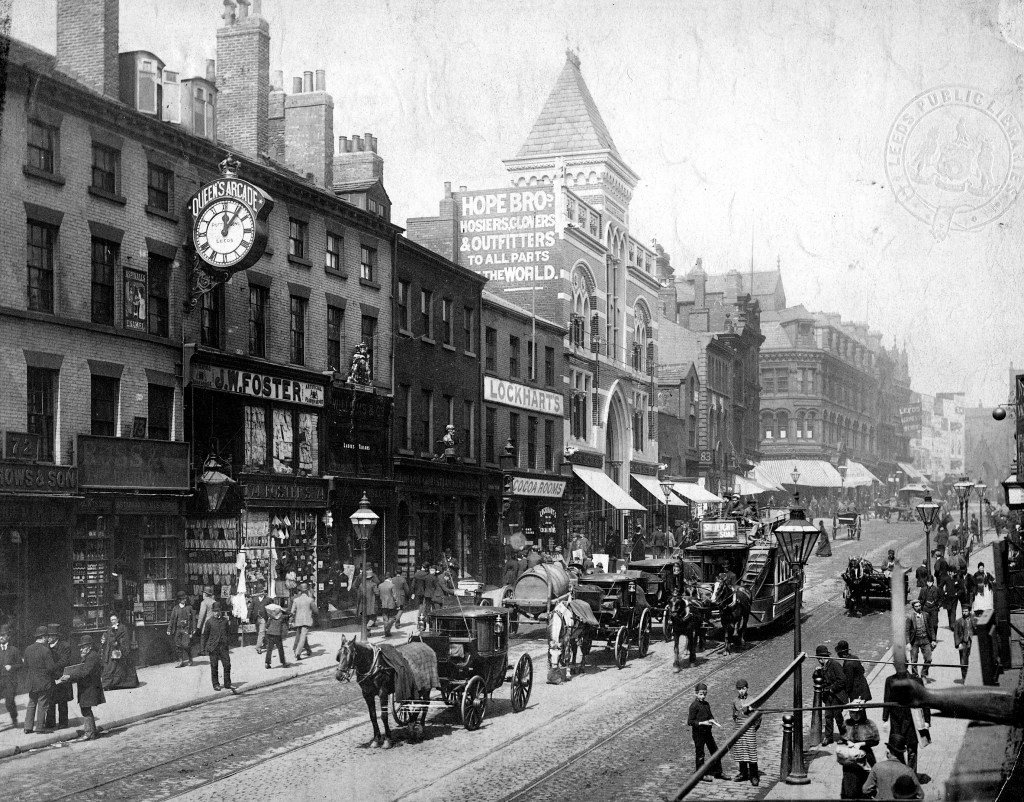

Eliza was born on 10 December 1803 at Briggate, Leeds, of educated parents. Her father was an auctioneer and valuer, and her mother had been educated as a child and ran a school for young ladies. Her family fell on hard times and by 1809 they were in the Leeds Workhouse. Her father then absconded from the workhouse leaving his family there, dependent on the town council. There can be little doubt that Eliza’s mother helped her leave the workhouse and live as a family unit. In her early life, Eliza and her sister Ann acted in amateur theatre productions. When Eliza was 21, she and her sister were recruited from the Theatre Royal at Richmond, Yorkshire to join an amateur company on the Isle of Man in about 1823. The company, at the New Theatre, Athol Street in Douglas, ran into financial difficulties and the sisters had to return to Leeds. A benefit concert was held for them in 1824 to assist with their fares home. In 1825, Eliza published in the Isle of Man her first book of verse, A Legend of Mona.

In 1828, she married James Green, a comedic actor, and lived in Manchester. Eliza participated in literary life in Manchester and had a poem, Children Sleeping, read at a meeting in the Sun Inn, Millgate, Manchester on 24 March 1842. This poem reflected her deep love for her children. The first verse is given below.

Flowers of my life! how sweetly are ye folded

In the calm stillness of your happy rest;

The fond reliance that an angel watches

Your tranquil slumber, fills each infant breast:

And the young lips, whose last sweet breath was prayer.

Smile, as if seraph music lull’d ye there!

The poems from this meeting were later published as the Festive Wreath, edited by John Bolton Rogerson. Eliza also had her work published in the Athenaeum Souvenir and William Gaspey’s Manchester Keepsake.

Eliza had returned to Leeds by the year 1830 and had six children there, of which three died in infancy. Her intense grief found expression in several poems. Her first born, William Henry, had died in 1831 at eleven months. The opening verse of her poem He Died! is given below.

He died!—they are but simple words

But oh! the withering pain

Th’unchanging grief those words have raised;

Grief, wild, and deep, and vain.

Throughout her life, she wrote poetry, which was published widely in newspapers, principally The Leeds Intelligencer and Isle of Man papers. She also wrote for Bradshaw’s Journal, The Bradfordian, The Oddfellows Quarterly Magazine and several others.

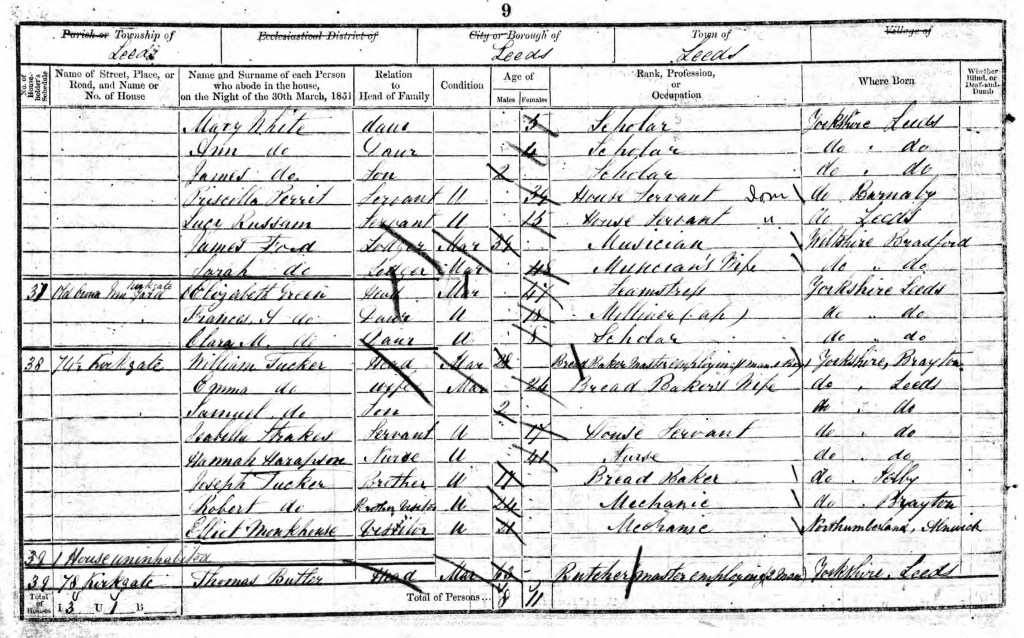

In 1851, the census records Eliza as living with her two daughters. Her husband had previously deserted her, and had taken their remaining son, Henry Hawes Craven, with him to London. The census records her occupation as ‘seamstress’. Without the support of her husband’s earnings Eliza faced a stark choice: starvation or prostitution. A seamstress’ earnings were expected only to supplement a husband’s income and were always below subsistence levels.

Eliza’s response was decisive; she harnessed her innate poetic skills to writing short stories, for which she was paid. The very few she had written earlier had been published, probably for little reward, mainly in journals which were male oriented such as The Odd Fellows Magazine. In 1846, a French fashion journal began issuing an English edition. It was Le Follet, Journal du Grande Monde, subtitled Fashion, Polite Literature, Beaux Arts, etc, etc. Eliza (using the pen name Sutherland Craven) had a story called The Dream Bride of Rosenheim in the first English copy. It is subtitled A Legend of the Rhine and is a tale about the last heir of Baron Rosenheim who was not inclined to marry and continue the line. The heir was entranced (by mind-altering herbal mixtures) into believing he had fallen in love with a beautiful but fated ancestor. For this and subsequent stories Eliza would have been paid a significant sum. Over the next 20 years she wrote 149 more stories for the journal. It was the ideal platform for her work; the readership was predominantly female and well off. She rarely used her own name but had a variety of pen names, often suffixed with ‘Esq’.

Ellan Vannin, the poem for which Eliza is most known was published in 1854 in the Isle of Man.

In 1858, Eliza published a collection of 137 poems entitled Sea Weeds and Heath Flowers or Memories of Mona.

Her elder daughter, Frances, was engaged to the artisan poet James Waddington (pen name Ralph Goodwin). Tragically he died in 1861 before they could be married. Eliza collected his poetry, published in 1862 as Flowers from the Glen, the Poetical Remains of James Waddington. Sir Titus Salt paid the costs of publication.

Throughout her life, Eliza was undoubtedly very poor, as is revealed by the addresses in Leeds we have from the 1841 and 1851 censuses. Her occupations, usually as a seamstress and/or milliner and lack of servants, further confirm this. Her husband had left her to live in London by 1841. Around 1860, she moved to better surroundings at number 6 St John’s Place, Leeds. There, she was a neighbour of Richard Kemplay, the editor of The Leeds Intelligencer. The Royal Bounty Fund awarded her a small pension of £25 a year in 1857 for services to literature.

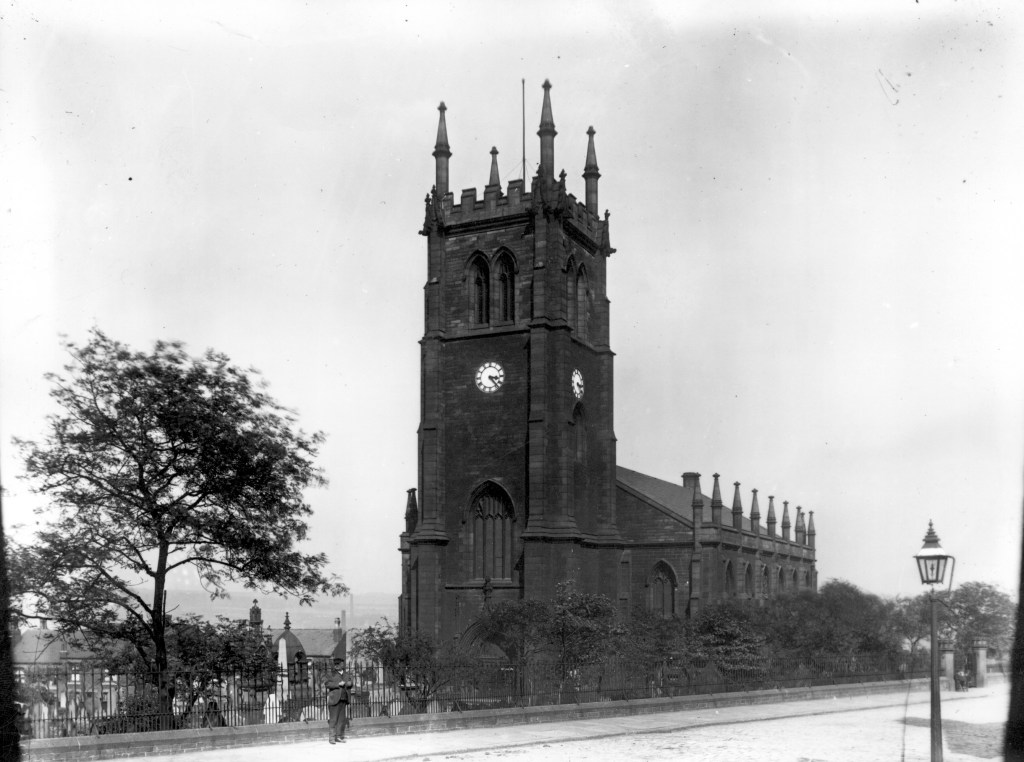

Eliza died after a prolonged period of ill health at number 80 Meanwood Street, Little London, Leeds on 11 March 1866. She is buried at St Marks, Woodhouse, Leeds. Her gravestone, which is close to the North aisle of the church, is not contemporary with her death as it gives information about the much later deaths of her husband and daughter Clara.

More details of the life of Eliza can be found in my book about her entitled Poverty, Passion and Poetry. The life of Eliza Craven Green, Seamstress, Actor and Poet.

Ellan Vannin

In 1854, the same year it was first published, Eliza’s poem Ellan Vannin was adapted and set to music by a contemporary Manchester composer J. Townsend. (Townsend’s initials include T, F, H and J: he is variously referred to as both J. Townsend and F. H. Townsend.)

It was widely used an anthem for the Isle of Man until ‘O Land of our Birth’ became the official anthem in 1907. Ellan Vannin is still a much-loved song, especially famed through the moving renditions by Robin Gibb and the Bee Gees.

The first verse is given below.

When the summer day is over

And its busy cares have flown,

I sit beneath the starlight

With a weary heart, alone,

Then rises like a vision,

Sparkling bright in nature’s glee,

My own dear Ellan Vannin

With its green hills by the sea.

Performances of Ellan Vannin by Robin Gibb, by the Bee Gees in commemoration of their birthplace, are available on YouTube.

A copy of Ellan Vannin: Arranged for a Chorus of Mixed Voices, published in 1949, is held at Leeds Central Library. Townsend is referred to here as F. H. Townsend.

Eliza’s Stories

Making a collection of some of Eliza’s poems for publication in The Hidden Poems of Eliza Craven Green 1803-1866 was not too difficult although there remain many more yet to be printed.

However, her stories presented a greater challenge. In all they came to over 500,000 words which had to be copy typed from, often difficult to read, downloaded or photographed, original sources. This was beyond my capability and was done for me affordably in India.

Before publishing they needed further proof reading and editing. This process was time consuming and would have delayed a book by several years. A learned Professor friend advised placing the stories, as I edited them, onto academia.edu where they can be seen by anybody. They are now being uploaded at intervals, if you search under my name, you will find them.

Significance

Hidden Poems includes several poems Eliza published in the Leeds Intelligencer. Three are on the local topics of The Harrison Portrait (the merchant and benefactor, John Harrison, 1579-1656), The New Infirmary at Leeds, and In Templenewsam.

Eliza’s poems and her stories covered many aspects of daily life, current affairs, romances, her love of flowers and children. However, they also touched upon important social issues such the needs of the poor and the role of women. In particular the stories are important historically as they provide an accurate contemporary picture of many aspects of Victorian life.