The third part of Joey Talbot’s trilogy of articles exploring the collections of the Morley Museum. Part 1 and Part 2 were published over the last two weeks and we strongly recommend reading them before diving into this final section….

So now we come to the third part of the story of the Morley Museum. We’ve investigated the museum’s historic acquisitions and dug through a box full of documents to find out what happened to the collection when the museum closed in 1966. The final task was to find some of the objects in their new homes!

On a sweltering summer’s day I cycled over to Birstall to dig through the archives at the Bagshaw Museum and Oakwell Hall. As we saw in the previous post, Batley Museums were given first refusal of the former Morley collection, so this is where many of the most prized items seem to have ended up.

Up in the storerooms, Frances Stonehouse of Kirklees Museums and Galleries dug through the boxes to seek out treasures. First up, two Chinese money swords. Often used to give protection from evil spirits, these swords may be hung above the bed of those sick with fever, or used during a woman’s confinement, according to the British Museum. Some of the coins in these swords were inscribed with what looked to my untrained eye like traditional Chinese characters, but on other faces were very different looking inscriptions, perhaps in the Manchu script as explained in this Lincoln Museum guide to Qing dynasty coins.

According to the guide, characters in Manchu script are placed on the reverse side of coins and record which mint the coin was produced in, while the traditional Chinese characters on the front of the coin name the emperor under whose reign the coin was produced. The front of a coin contains four Chinese characters, which are read top to bottom then right to left. The top and bottom characters give the name of the Emperor. The right and left characters reveal the type of coin, such as tongbao: ‘circulating treasure’, or Zhongbao: ‘heavy treasure’. The Qing Dynasty lasted from 1644 to 1911, and these two swords were donated to Morley Museum in 1907.

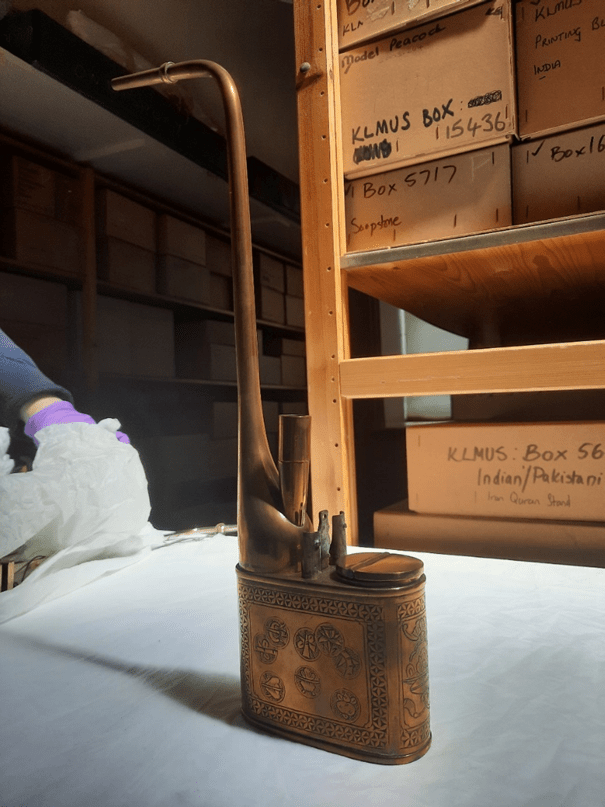

We found several other Chinese objects too. One had been described in the accessions book as a ‘Chinese pipe’. I was expecting a tobacco pipe, but it turned out to be a beautiful metal opium pipe, about 50cm tall with an engraved bowl.

Opium imports were forced on China by the UK and other western powers, with the Opium Wars running between 1839 and 1860, resulting in the ceding of Hong Kong Island to the British, the legalisation of the opium trade and the opening up of China to British merchants – a period that has been dramatically fictionalised in Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy.

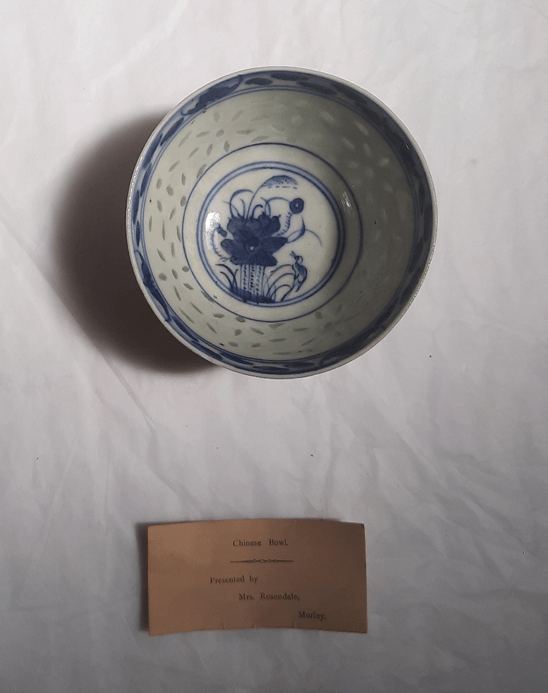

Continuing the Chinese theme we had a ceramic rice bowl, the design using grains of rice to create semi-transparent spots within the bowl.

Finally this pair of wooden slippers are beautifully painted but look like they might not be the easiest shoes to wear.

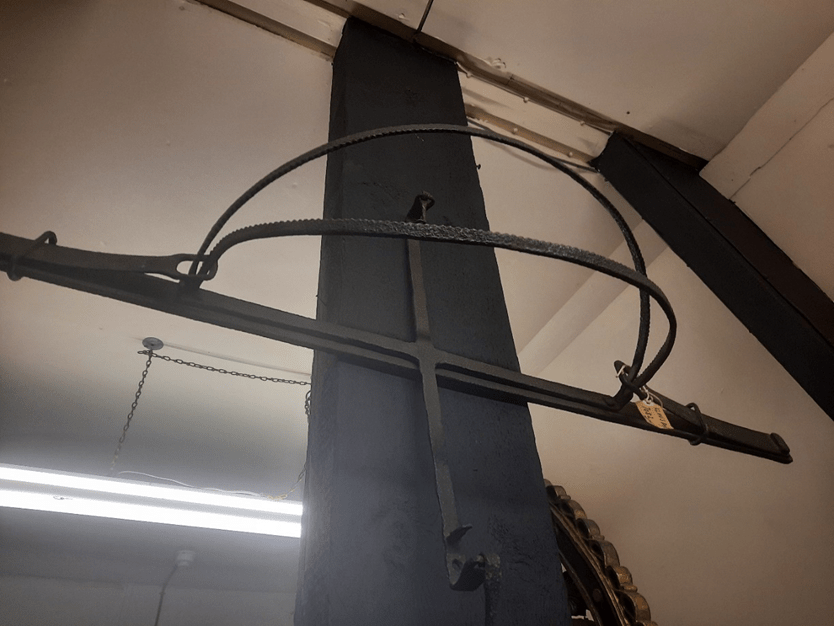

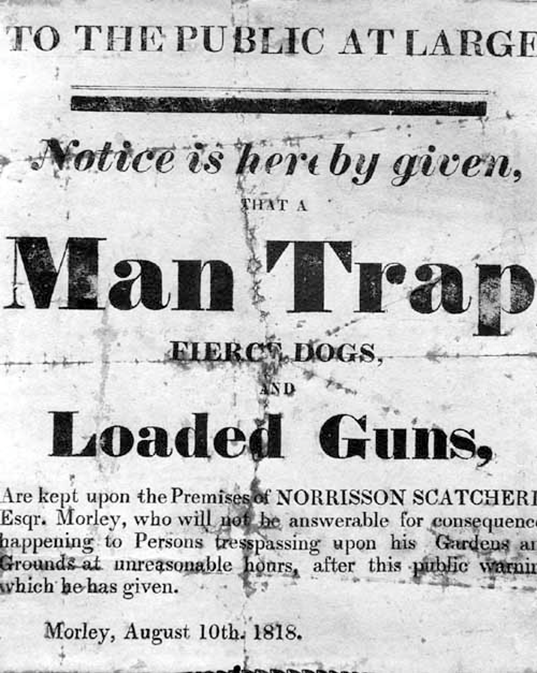

Moving on to something totally different, we have here a man trap which used to belong to Norrisson Scatcherd, antiquarian and famed author of the history of Morley. He was also the father of Oliver Scatcherd, the Morley Mayor who, as we saw in my previous article, played a match of clown cricket with a cricket ball made of slag, which he later donated to the museum collection.

The man trap was donated alongside a notice that warned the public against trespassing on his Morley House estate, promising fierce dogs and loaded guns as well as the man trap itself.

The trap is a nasty looking contraption and I wouldn’t want to get caught in it. But it’s not the only medieval looking implement Scatcherd owned. At Leeds Discovery Centre there’s a scold’s bridle, a helmet-like iron frame with a spiked iron plate that was forced into the unfortunate victim’s mouth, in a punishment that was meted out to those, often women, who were deemed to have spoken out of turn. And yes, this scold’s bridle was donated by none other than Norrisson Scatcherd. Did he have a particular interest in collecting punitive ironmongery?

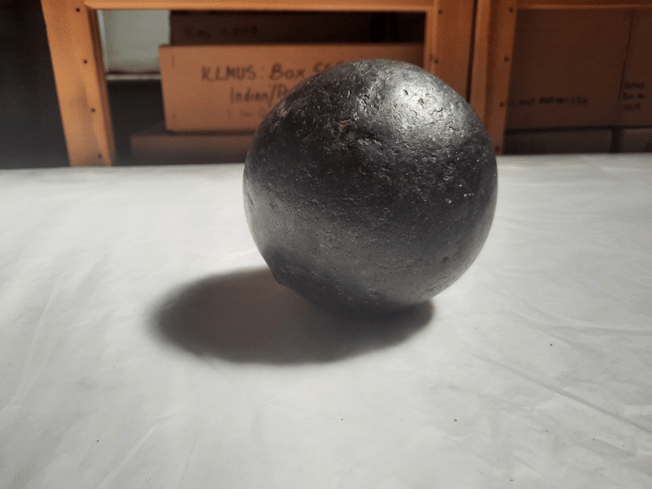

Speaking of objects built to cause maximum destruction, next up is the cannonball from Sebastopol. This may have caused more damage in Morley than in Crimea, going by its relatively pristine, unfired appearance (compare this picture with my next cannonball image), along with the incident recounted in the previous blog when it came loose and rolled down the stairs during its removal from Morley Museum.

Of all the ex-Morley items at Bagshaw, only one of them is on display, and that’s the mummy’s hand. It’s in the Egyptian gallery and it’s a full hand and lower arm, surrounded by scenes of hieroglyphics, natron used for embalming and aromatic crystals of myrrh.

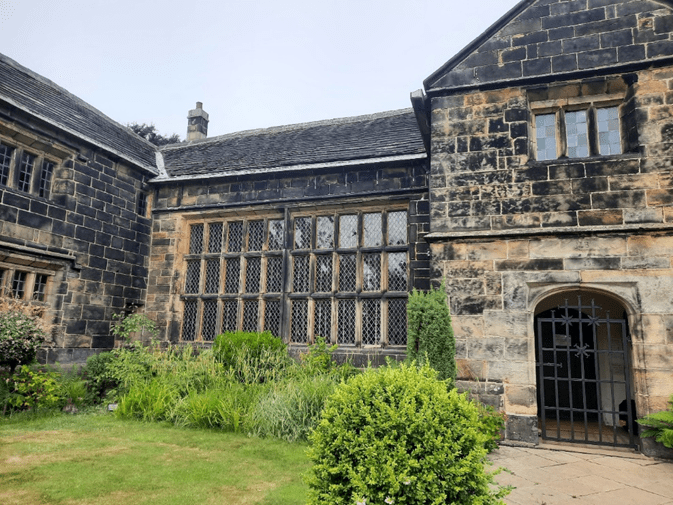

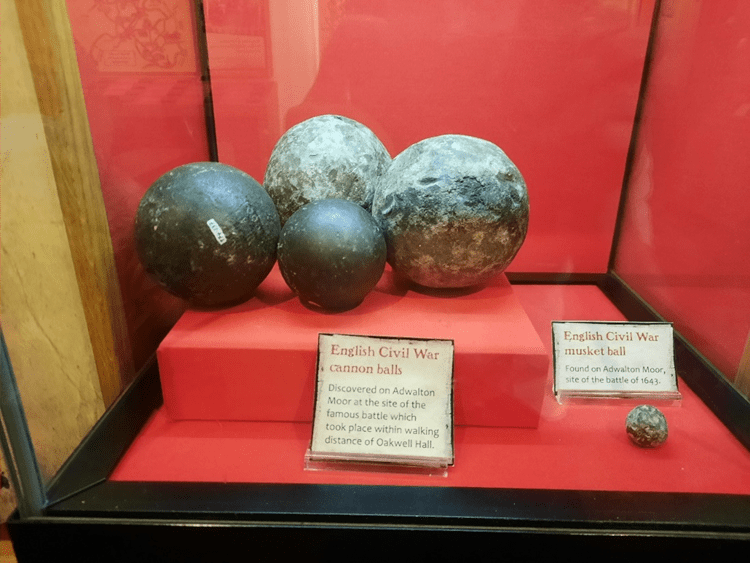

For the second half of my grand tour, I cycled across town to Oakwell Hall, now home to two items from the Morley Museum collection – the Adwalton Moor cannon ball and the painting of the Earl of Newcastle. A prestigious building, Oakwell Hall was known in particular for its famously large windows.

Oakwell Hall has quite a collection of cannonballs. We can see a clear difference in appearance between the balls that have been fired – which are discoloured and full of pockmarks – and the ones that haven’t been, which are black and shiny. We believe the Morley Museum cannon ball is the large ball on the right, one of those which clearly shows the effects of having been fired.

On display in the dining room at Oakwell Hall, the second Morley Museum item was the painting of the Earl of Newcastle, who commanded the victorious Royalist troops at the nearby Battle of Adwalton Moor. We don’t know who the artist was but the painting appears to be a copy of a work by William Dobson. Dobson’s original is said to perhaps be in the collection of the Museu Gulbenkian in Portugal, and there are records of a Clumber auction in 1937, but we know very little about the origins of the painting at Oakwell Hall.

That’s all in terms of Morley collection items, but I was also treated to a little tour of the stunning Oakwell Hall, and got to peek at a beautiful red dress, made by women from all around the world, which was being exhibited there.

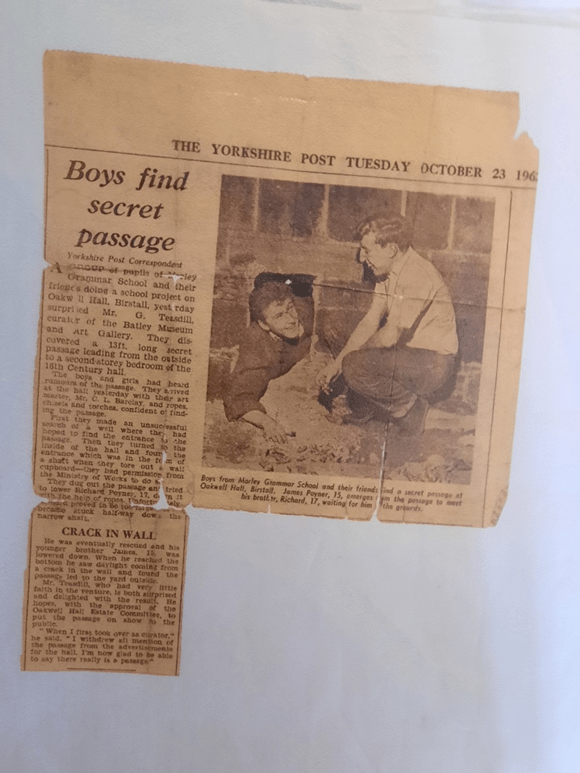

Another story concerns a group of Morley Grammar School students who found a secret passage within the hall. They came equipped with ropes, chisels and torches, and with permission from the Ministry of Works began searching for the rumoured passage. When they found it and began digging it out, one of the boys got stuck halfway down and had to be rescued by his brother. Eventually the excavation was complete. The passage is now on display in its original form as a (thankfully unused) long-drop toilet.

On the way back home, a small detour took me onto the Adwalton Moor battlefield. Now distantly surrounded by residential streets, Drighlington Moor contains a series of stones bearing descriptions that give us glimpses of how the battle progressed. So much history lies waiting when we start to investigate…