This week we hear from regular guest contributor Tony Scaife, who has been exploring the history of an important local news publication…

Leeds’ had two newspapers – the Leeds Mercury and the Leeds Intelligencer – for most of the 18th century. I have been fortunate enough to spend some time with the Local and Family History Library’s copy of the bound Leeds Mercury 1776-1784 (SRF 2 072 MER). What a treasure it is.

I am looking at the impact of the loss of the American colonies on Leeds and the date range here was ideal. But I defy any reader to come across old newspapers and not become side-tracked.

The newspaper masthead reads “The Leeds Mercury printed by James Bowling in Boar Lane,” with the subheading “This paper may be constantly seen at the Chapter Coffee House St Paul’s Churchyard; at the Coffee House, Ludgate Hill”. What makes this bound volume especially noteworthy is that they are almost certainly the Boar Lane office copies of the Mercury.

The Leeds Mercury was first published in 1718 but it closed in 1755. Bowling re-launched the title in 1765 and published it until 1795 (Thornton). Our volume came into the library in 1911 when “the Chief Librarian reported “gifts by the Proprietors of the ‘Leeds Mercury’ of volumes of their newspaper dated from 1737 to 1814”. (Minutes of the Council Library Committee for April 9th, 1911) At some point before then the individual folio size four column, four-page weekly papers were bound together, within heavy, leather-edged, gold tooled boards.

The Mercury was a weekly newspaper published on large plano folio foolscap ( approx. 13 ½” x 171/2”), making it an unwieldy object to read comfortably. It would have been printed on a wooden screw press. (There is a link in the appendix to Wendy Westwood’s YouTube Video of a replica 18th Century press). Bowling used a Caslon typeface – modern by the standards of the time. Though he stuck to the long-established printer’s convention of the long s – a piece of type like a lower-case f that was used at the beginning or middle of words. The long s convention would disappear by the end of the century.

Long s or not every letter of every word had to be picked from the type case and set, in a composing stick, by the hands of a highly skilled, highly paid, literate compositor, They had to be able to read text backwards and know , by sight, when to add blanks, leads and slugs to get the spaces between words and lines; to produce a readable, justified, four column text on each page. (See the link in the Appendix to National Printing Museum composing video in the appendix). Once composed the type was set and fixed in place on the stone. (See in the Appendix the link to Claire Westwood’s video of the skilled, labour intensive process needed just to apply ink to the type).

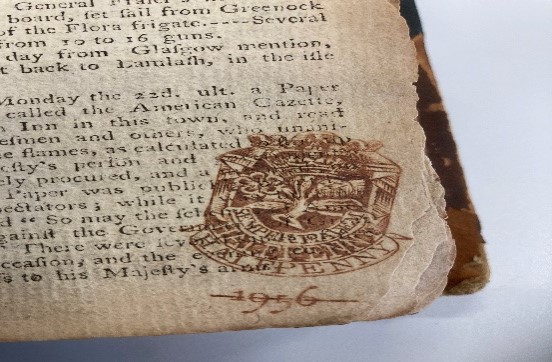

After inking, two men would be needed to place the individual sheets of paper on the type and screw down the platen to create an even impression. 200 sheets an hour was thought to be a good speed. The printed sheets were then collated into the four-page weekly newspaper. Finally, by law, from 1712 to 1855 each newspaper copy had to be embossed with an official stamp. This helped the authorities to both control the press and raise revenue.

This collection of newspapers papers do not seem to have come from a private library. Instead, they are an eclectic collection of manuscript and printed papers, bundled together in haste and subsequently very carefully conserved and bound. Sometimes there are handwritten sums in the margin; sometimes ink splattered pages, perhaps deemed unsaleable. Bound in we also find two copies of the rival The Leeds Intelligencer along with several more Intelligencer cuttings. Then there are over thirty manuscript and other printed matter, each carefully, but at random, pasted (tipped) onto pages. For example, as manuscripts: a copy of a John Milton poem; a birthday note to an unnamed girl; numerous mourning texts and copies of memorial headstone inscriptions, as well as a printed letter dated 1793 and many printed, lengthy religious texts. I had hoped that the manuscripts at least were the actual copy once given to the compositors, but no luck yet in finding them in any of the columns.

There is another little puzzle. In one or two copies of the Mercury in this volume and another from slightly later date, there are instances where a section of the text has been excised from the page. Clearly a careful, deliberate act rather than accidental damage. Why?

Thornton rather disparages the Leeds Mercury as “as a scissors and paste job,” saying it mainly consisted of reports taken from other newspapers. This, I think, misses the point: with the Mercury we are seeing the very early days of the concept of news itself. News for Bowling’s readers was a much less refined product than we are used to. It was largely the reader who had to join the dots and make sense of a report.

Journalists and editors, as a profession, hardly existed in the 18th Century. The London Times, for example, did not begin publication until 1785. Today there are news agencies providing regular, reliable, almost real time news of events. Bowling had to rely on much slower and irregular sources of news. Clearly he did have a network of presumably paid agents, sending him reports from London, Hull, Liverpool etc. But there is no clue in the newspapers themselves as to how this new gathering network operated.

Be that as it may reports came to the Boar Lane office irregularly. Foreign news, at the speed of a wind and weather dependent sailing ship; for other news, at the speed of a horse. As an illustration, The Mercury itself (11/6/ 1776) advertised a new steel-springed, thirty-nine-hour stagecoach service to London. At this time, an inside seat for 35/- was very expensive indeed. Bowling had to rely on what second hand reports he could get. He had neither the time nor the money to be regularly sending anyone to-and-from London, or elsewhere.

It was the reality of his age that the weekly Mercury reports were often weeks or even months old by publication day. But why is each column of each page such a haphazard collection of topics? For example, a page may well have news of ships arriving in Boston, followed by the story of the landlady of a pub in Oxford who was bitten by a snake in her cellar, then announcements of weddings or funerals, presumably paid for, followed by more shipping news from Jamaica and reports of ships lost, then a list of ships arrived at Hull, troops landed at Quebec, a notice about runaway apprentices and a man denying any responsibility for his wife’s future debts since she has ‘eloped ‘ away from him.

Spread across the four pages there will be similar disjointed reports about the war in the American colonies: regiments arrived, troop movements across all the colonies, statements from the British Government and from the newly installed Congress. Nowhere is there any attempt to explain or interpret these reports – not even a map to show where the North American places were.

Bowling’s readers would have grown up in a world where any news of events had always arrived in snippets. There would be plenty of time to mull over the snippet before another report arrived. But why make it so hard for the reader to follow a particular news thread – say, shipping news, news from America or London? The answer: Eighteenth-Century printing technology simply could not produce a final text that was in a more easily comprehensible, digestible news format.

A skilled compositor could work fast, but not fast enough to be able to set the whole newspaper in one day. Even a team of compositors – if they could be found and there were enough type cases and money to pay them – would struggle to do it, especially at times when day light was short and artificial lighting poor. There was no practical alternative. Reports had to be set as they arrived, albeit in dribs and drabs. Then, once set into columns and pages, altering them, to accommodate, say, a new report, was probably unthinkable.

To produce a map or any illustration needed hand engraved plates like this LGI example. Engraving was an entirely separate, very skilled and very expensive trade. Regularly, commission engravings was beyond the pockets of most printers. Apart from the LGI plate, itself pasted in to cover the title masthead, there is only one other illustration for the whole of 1776 – a small engraving of Mr. Blenkinsop’s machine in Hunslet. (31/12/76)

Once the newspapers had been printed most of the text had to be broken up and returned to the type cases ready to start again. However, the title masthead probably remained set as did some adverts that ran over weeks. Also remaining set was our final gem for a glimpse into 18th century news gathering, production and distribution.

At the foot of the last page there is a list of The Mercury’s agents across twenty-five towns in the West Riding. Mostly they were printers and booksellers and who would collect subscribers’ payments, as well as the copy and payment of those wishing to place advertisements. So, whilst we do not have to hand details of how James Bowling was able to do business outside the county, with these few lines of text we do have an insight into his network of trusted commercial relationships in the county; a network that, by carrier, coach and packhorse, kept newspapers, reports, adverts, and money flowing through the network – thus laying the foundations that would make Leeds a major newspaper, printing, and broadcasting centre in the subsequent centuries.

Bibliography

Thornton, David. Leeds: The Story of a City (2002), p.89 et seq.

Appendix

National Museum of Printing. Hand Composing – YouTube

Wendy Westwood Replica 18th Century American printing press.

18-century Printing Press – inking and printing, 3.02 mins Claire Eastwood. 18th Century Printing Press – YouTube

Most enjoyable and technically very well described…

Thank you Michael. I am pleased you enjoyed it. The bound Leeds Mercury is kept in the library’s strongroom but maybe you could arrange a visit with the staff and see it for yourself. Well worth the effort!