This week on the Secret Library we hear from one of our heritage volunteers on a significant piece of cataloguing work we’ve asked them to help us with…

Hi. My name’s Andy Armstrong and I have taken on the task of sifting through 200 years of Leeds City Council papers held by the library to bring some structure to them and to produce a series of research guides.

I have just completed my second guide, this one being on Health, covering all aspects of health for which the Council has responsibility, and these areas are currently covered by the Council under the headings of Health & Social Care and Public Health.

Leeds City Council (then called Leeds Corporation) became a local authority as we know today following the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. At that time, its role was mostly around the election of Aldermen. Health issues did not concern the Corporation: hospitals, like the General Infirmary (LGI) were funded privately, often through charity or subscription, while others, like St James’, were workhouses that provided some basic healthcare only.

At the time, Leeds was a booming town and had all the problems associated with a rapid influx of people: overcrowded slums and poor sanitation. Illness was rife, epidemics frequent and infant mortality was frighteningly high.

Throughout the 19th century, Acts of Parliament gave the Corporation the powers to address many of these problems. The Leeds Improvement Act 1842 required proper paving, drainage and sewerage of new streets, but it wasn’t until the Public Health Act of 1875 that things started to improve.

Hospital services remained outside the control of the Corporation, with LGI actively campaigning to retain its independence from the bureaucratic Council. But the private sector could not provide many of the services needed, and towards the end of the century, additional functions were placed on the Corporation; for building, and maintaining hospitals for infectious diseases (primarily those at Manston (Seacroft) and Killingbeck), and caring for those with mental illness (such as Meanwood Park Hospital).

In the 20th century, the City Council added social care, care of children and many other functions. Following the establishment of the NHS in 1948, some functions (eg. ambulance services, midwifery, vaccinations) gradually transferred from the Council to the NHS, while others (social care) remained. Joining up these services alongside the NHS remains an issue today.

A key part of the improvements were driven by the Medical Officer of Health, appointed by the Council from 1866 and 1973. This allowed the Council to take a strategic overview of the health issues across the city and to make sure services were joined up. J Johnstone Jervis was a particularly active and longstanding Officer and held the position between 1919 and 1947. He was a passionate advocate for a national health service, but one that was run by local councils rather than central government. The familiar story was that central government did not trust, nor could easily control local councils.

Despite all the administrative actions, the most remarkable changes have been in the improvements in health across the city. In 1874, deaths from scarlet fever, diarrhoea/cholera and tuberculosis were 663, 484 and 785 respectively. Infant mortality that year was 189 per 1,000 births. Today, these illnesses barely exist, while infant mortality has reduced to 5 per 1,000 births.

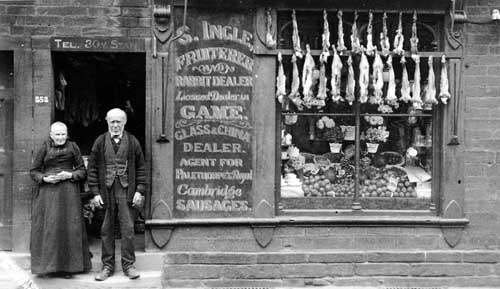

In public health, changes have been equally dramatic. For example, a 1906 survey found that 25% of all food in Leeds was adulterated. And in 1885 concerns about diseased meat and its conversion into sausages led the Medical Officer of Health (Dr George Goldie) to say “They constitute a luxury of which I, personally, am not a consumer. I look upon a sausage as a conundrum, which I never allow my stomach the chance of solving”.

Fascinating post, thank you 😊 I’m a health librarian who does some partnership work with my local public library so I really enjoyed reading your historical context 😊

Thank you – a great outline of changes in health provision by Leeds City Council and its predecessor. It would be good to see housing provision addressed, as that has been shown to be a vital factor in improved health in the population.