This week we hear from Tony Scaife, regular guest author on the Secret Library Leeds, who explores the anniversary of a little-known but hugely important moment in the history of technology, media and broadcasting in Leeds…

Monday July 8, 2024 marks the 100th anniversary of public wireless (radio) broadcasting in Leeds. The Local and Family History section of the Central Library decided to mark the occasion with a short blog, looking at some of their resources which tell the story of that momentous day, as well as some of the Leeds people who were involved in the earliest days of 2LS.

First though there is a little-known back story to wireless telegraphy in Leeds. A.M. Bage claims the title of the earliest wireless experimenter in Leeds. In 1908, only ten years after Marconi invented wireless telegraphy, he began experimenting with wireless transmission; first from one room to another in his home in Providence Avenue, Woodhouse and later being able to send longer Morse code messages to his friend nearly a mile away in Belle Vue Avenue. Things progressed from there and by 1912 there were about a dozen Leeds people with radio receiving sets. They and some other friends, gathered to form the Leeds Wireless Club. (Leeds Newspaper Cuttings, Volume 13, 1920-24, p 71 column 3).

The outbreak of World War One in 1914 led to a very large expansion of wireless. For example, by 1917-18, the Leeds Wireless Club was helping to train over 400 telegraphists for the Merchant Marine. (The Wireless World and Radio Review, 1922, p.730)

So, at war’s end, there were experienced amateur wireless enthusiasts, demobilised wireless telegraphists, and wartime wireless equipment manufacturers. Each of these groups were ready to take wireless into the civilian world. But, as Mr Bage said, “The dot and dash code is a little lacking in appeal…The sound of the human voice was needed to realise the full miracle of wireless.” (op.cit.)

And, on June 15 1920, what a sensational voice they got: in one of the Twentieth Century’s greatest publicity stunts the Marconi Company paid renowned opera star, Dame Nellie Melba, to give the first ever live, worldwide radio broadcast performance. (Read more: Marconi Radio broadcast that changed the world.)

Leeds Wireless Club members were greatly impressed.

“That was the first voice I heard and amateurs throughout the country early recognised that this step would lead to things.” (A M Bage op.cit.)

So profound was the effect that the Leeds Wireless Club members decided to immediately close their club and reform as the Leeds Radio Society.

Two years later the Marconi company and others successfully petitioned the Postmaster General for a licence to present weekly concerts and, on November 14 1922, British Broadcasting Company began broadcasting from its 2LO station on Savoy Hill in London. The studio had a control room where two landlines carrying the signal from London were received, amplified, and sent to the transmitters in Sheepscar and Westgate. But it was not just a relay station. The control room also managed broadcasts produced in the studio. From the control room window, the engineers could view the specially constructed

“…concert room… the floor is heavily padded and covered with a hair carpet. The walls and roof are draped with curtains to minimise echo … the only furniture are a table and one or two chairs, … the microphone is similar to a telephone earpiece only larger and supersensitive. The performer or instrumentalist will be placed about 3 ft. from this.”

op.cit. col 1-2

The 2LO transmitters were not powerful enough to be heard across the country. Thus, a network of relay stations, in various cities, was needed to boost the signal for national transmission. 2LO broadcasts would be fed live into the telephone network and be received by two dedicated phone lines in each relay station. In February 1924 the BBC had received permission to establish relay stations in Plymouth, Edinburgh, Liverpool, and one between Leeds and Bradford (The Times, February 2 1924, p. 8) and, on February 12, a later report established that the Leeds-Bradford station would have the call sign 2LS.

Work started immediately on 2LS. Firstly, transmitters had to be erected and earthed. For Leeds, this meant a 210 ft. aerial on Claypit Lane in Sheepscar transmitting on 246 metres with 200-watt power.; similar work was done for Bradford’s Fountain Street, Westgate aerial – at 160 ft with 200 watts power and transmitting on 310 metre wavelength.

“That so many congratulatory messages have been received … from enthusiastic listeners speaks volumes for the efficiency of the earth and aerial systems.”

Leeds NC op cit. col. 2

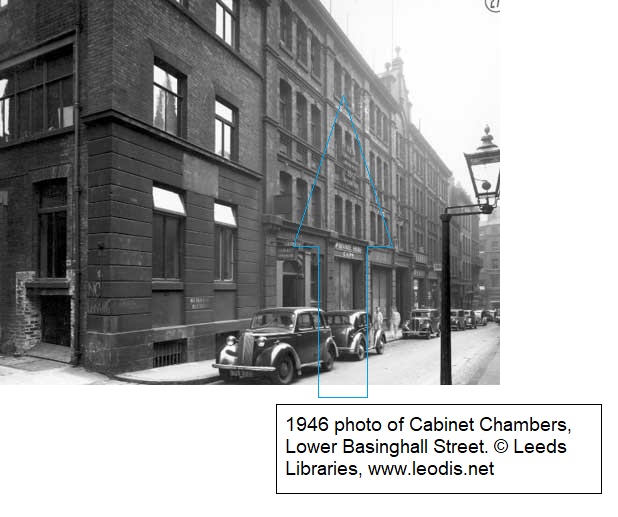

No doubt the members of the new Leeds Radio Society were very interested in the technical details of the transmitters but perhaps the general reader is more interested in where the studio for 2LS was? Not too far from the Central Library, in fact: on the upper floor of the Lower Basinghall Street’s Cabinet Chambers. Interestingly the street at that time was clearly a kind of media hub with film distributors and the offices of the Daily Mirror already established.

Transmitter and studio works were complete and ready for the first 2LS broadcast on Tuesday July 8 1924.

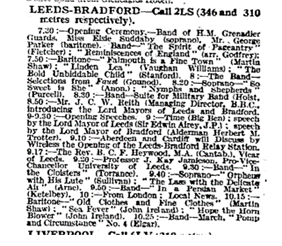

Sadly, there was no recording of the broadcast. All we now have about the programme is The Times programme listing for 2LS on Tuesday July 8 1924. At this point I am sure the reader is asking how the Band of the Grenadier Guards could possibly fit into the Basinghall Street studio?

Well, they didn’t. They, and other performers, spent much of the day in Leeds Town Hall rehearsing and sound checking, ready to transmit their performance over the line to the 2LS studio. Most of the distinguished guests were also in the Town Hall for the broadcast, even though the Basinghall Street studio had specially furnished green rooms. (‘First Leeds’ Wireless Concert,’ Yorkshire Evening Post, July 8 1924, p 4.)

John Reed as Managing Director of the British Broadcasting Company opened the broadcast speeches. But it was Arthur Burrows, Director of Programmes, and, as Uncle Arthur, a regular broadcaster, who has left us with the best reflections on the impact of the day –

“The most interesting thing in broadcasting at the moment is bringing England into the home. … [the new station] will bring pride of place to Leeds and Bradford. In addition to what is happening in London you will have definite local programmes and the opportunity of comparing what can be done by local people. I can well imagine that there will be some surprises.”

YEP op.cit.

Receiving broadcast in the home was often a hit and miss affair in the early days when people relied on primitive ‘cats whiskers’ crystal radios. The listener needed earphones to hear the signal.

“The great unseen audience which heard last night’s concert at Leeds Town Hall has acclaimed the complete success of the opening ceremony of the twin wireless relay stations of Leeds and Bradford”.

YEP July 9, 1924, p 5

Those listening on crystal sets at home apparently had a better listening experience than the audience at the Town Hall, whilst the Vicar of Leeds’ three-minute speech broadcast from London “… had undoubtedly the best reception.”

There were about 3,000 wireless licences issued in Leeds up to the launch of 2LS , with a late “rush for licenses”. Enterprisingly, Messrs Wadsworth, Sellers and Co. fixed a temporary aerial between a tree and the Mansion House in Roundhay Park to give an admirable demonstration. (YEP op. cit.)

But all was not completely satisfactory in the Leeds wireless world that July. Suddenly, there were government objections. The Claypit Lane transmitter was quite close to the Territorial Army Barracks where the Royal Corps of Signals practiced wireless telegraphy. If the transmitter interfered with the training, then the BBC would have to move it. The BBC’s assistant chief engineer was sent for earnest discussion with the military authorities and hopeful that daily broadcasting would be able to continue. (YEP op.cit.) The meeting must have been successful since broadcasting did continue and now t was time to see if Arthur Burrows hope that “the opportunity of comparing what can be done by local people” would be fulfilled.

For those willing to look, the Local and Family History Library has resources telling the story of many of the contributors to radio in Leeds. But this writer’s interest was piqued by three of the early broadcasters: all young people in at the birth of radio and ready to seize with both hands the opportunities it offered.

Firstly, we have Drighlington born Arnold “Mr Music” Luxom who first played the piano and read birthday greetings for the Children’s Hour programme in September 1925 – aged nine. His musical career, as an organist, brought him fame across Europe and America before he made his final broadcast 70 years later. (YEP Sept 9, 1975, p 6.)

Next is Sydney Errington whose views on the sound quality of the Basinghall Street studio we have already heard. He was a gifted violist and a pupil at Leeds Central High School where, with two school friends, he formed the Ebot Trio. Initially to entertain war wounded soldiers at the Becket Park war hospital but ready when the call came to step up to the radio microphone.

He was twenty years old when the Ebot Trio made their broadcasting debut. He arrived thirty minutes early and describes having to climb the long stairs to studio: “What a privilege”, he wrote, “to stand before the microphone and know your effort will reach the ears of countless thousands.“ He later estimated that some 20,000 people heard them that July night. (‘S E Broadcasting Notes – 1,’ The Palm 6(3), Dec 1925 p. 25-27).

Finally, we have a young Leeds woman, Maud Hummerston. She was the first children’s librarian for Leeds libraries and regularly toured the branch libraries to hold story time sessions for children.

In 1925 she took her storytelling skills and moonlighted with the Children’s Hour team at 2LS. As Aunty Norah she broadcast regularly. But, in 1929, when the British Broadcasting Company had become the British Broadcasting Corporation – financed by a licence fee – Maud was dropped from the Children’s Hours team. Apparently a listener had complained that “they didn’t pay their licence fee to hear a Yorkshire accent”. Rather a set back for Arthur Burrow’s promise five years earlier of “opportunities for local people”. (Maud Hummerston, ‘Through the pages of Time,’ YEP June 26, 1972 p4.)

What a fascinating piece. Thank you.

Glad you liked it. Thanks for the feedback

Where was 2LS in relation to the street today please. Is there a blue plaque?

Hello

Thank you for your interest in our Secret Library blog!

There’s currently no Blue Plaque for 2LS – perhaps this is a good time to start a campaign! Contact the Civic Trust if you want to submit the building as a possible Blue Plaque site: https://leedscivictrust.org.uk/whatwedo/heritage/blue-plaques/

We think the Cabinet Chambers were around where block 20a on Lower Basinghall Street is on this OS map: https://maps.nls.uk/view/210664408

Thanks again

Antony

Leeds Libraries