We welcome back researcher Danny Friar this week, to mark a very important anniversary: 190 years since the emancipation of enslaved people in the British Caribbean colonies. After reading Danny’s article, be sure to catch the Beyond the Bassline: 500 years of Black British Music exhibition currently on display at the Reginald Centre.

On the 1st August 1834, 190 years ago, the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 came into effect, emancipating over 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and other British colonies. Even though the act didn’t emancipate all enslaved people across the British Empire, and those who were emancipated entered a period of so-called apprenticeship, it is still considered a milestone moment in ending one of the most barbaric periods in history, that of Transatlantic slavery.

Leeds has, rightly so, celebrated, and reflected upon, the emancipation of the enslaved in the British Caribbean many times over the past 190 years. In this blog post I wanted to highlight some of those celebrations of emancipation with a special focus on the evolution of Caribbean carnival in Leeds, which is a celebration of emancipation at its core.

To understand the evolution of Caribbean carnival in Leeds we must first break down Caribbean carnival into its key components – music, masquerade, dance and outdoor procession. Combined, these elements have been used in the Caribbean to celebrate emancipation since 1834. In Leeds however these elements were not combined until 1967 therefore we will have to look at each one in turn.

Music and Dance

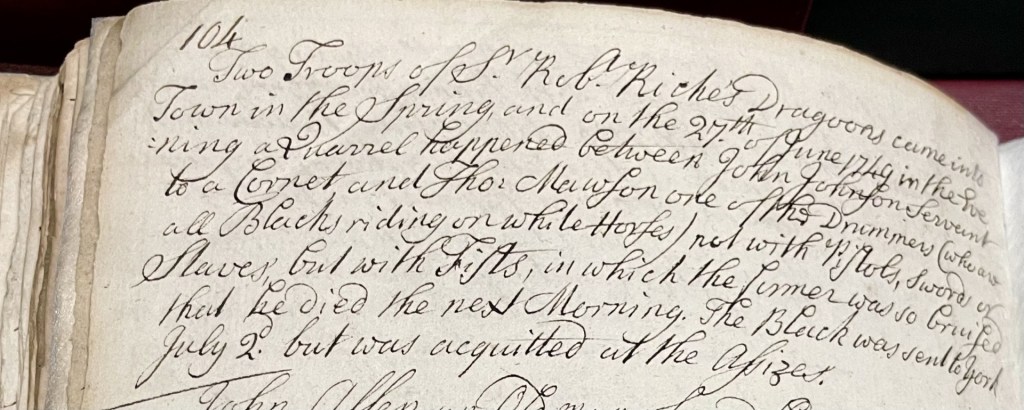

Caribbean music has a long history in Leeds that actually predates the existence of the city’s Caribbean community. The earliest documented Black musicians in Leeds were noted in the local press and in the diary of John Lucas in 1749. They were a group of drummers with Sir Robert Rich’s Regiment of Dragoons. The military drums that they played were the predecessors of the big drums or bass drums and the kettle drums traditionally played at Caribbean carnivals and carnivalesque traditions such as Barbados’s Crop Over and the Christmas Sports of St. Kitts and Nevis.

Military bands with Black musicians continued to appear in Leeds into the 19th Century and in 1843 a Trinidadian man named John Charles, with the 32nd (Cornwall) Regiment of Foot, played his big drum at the Leeds Zoological and Botanical Gardens. Both the 1749 and 1843 performances took place outside and it’s likely that the Black drummers with Sir Robert Rich’s Regiment of Dragoons were part of a procession along the streets of Leeds. They were known for riding on white or grey horses and were considered some of the best performers of their time. Another outdoor performance was documented in 1884 when a local Black man named Alexander Harris, the leader of his local Salvation Mission Army Band, played his kettle drum in the streets of Bramley. His Christmastime performance coincided with some carnivalesque performances in the Caribbean that traditionally take place during the Christmas period such as Jamaica’s Junkanoo and the Christmas Sports of St. Kitts and Nevis. In 1967 when the first Leeds West Indian Carnival took place the procession included a big drum and fife band made up of three self-taught local Black musicians; Henry Freeman on big drum, Prince Elliot on kettle drum, and Kenneth Browne on fife.

At the Leeds West Indian Carnival, big drum and fife bands are often accompanied by a group of masqueraders, following the tradition of Montserrat and St. Kitts and Nevis. The music and dance they perform is called quadrille and developed from the European music and dance of the same name. European quadrille dancing became popular across Europe from the late 18th Century. The Leeds Intelligencer mentioned the quadrille being danced in Otley as early as 1781. People from Leeds also composed quadrille music. ‘The Blue Belles Quadrilles and Waltz’ was composed by either John Hopkinson or his brother James around 1840. It was first performed by Mr Harabin’s Band at the Leeds Grand Conservative Ball.

Another traditional Caribbean carnival music is calypso. While calypso, developed in Trinidad in the 17th Century from African roots, didn’t reach a mass English audience until the early 20th Century, two local Black men from before that period are worth mentioning. A local Jamaican man named Joseph Downey was singing in pubs in Hunslet in the 1890s and another Black man, Pastor H. Smith, from Leeds was performing African-American songs in churches across England in the first decades of the 20th Century. The first local Black singer performing calypso songs was perhaps George May of Bradford who was performing in West Yorkshire during the 1930s. Two Jamaican singers are noted as living in Leeds during the 1940s. One, a young boy named Victor Garrick, became known as the ‘Singing Sailor’ during his short time in Leeds in 1942. The other, Cliff Hall, became known around the world as a member of the folk group The Spinners. Cliff Hall introduced mento, a Jamaican folk music similar to calypso, to the group’s repertoire. A third Black man living in Leeds during the 1940s was the Ghanaian percussionist Neemoi ‘Speedy’ Acquaye who went on to join Georgie Fame and The Blue Flames. A fourth local Black man, Bob Barclay, the tuba player with the Yorkshire Jazz Band, became the first Black musician from Leeds to record in 1949.

The earliest documented calypso performance in Leeds took place in 1953 when a local Black man, Dr Malcolm Joseph-Mitchell, performed calypso at the International Festival held at Leeds University. This performance predates the appearance of calypso superstar Lord Kitchener who played a gig in Leeds in 1954. A calypso band were noted as performing at Headingley Cricket Ground in 1957 but it is unclear if they were local musicians or visiting ones.

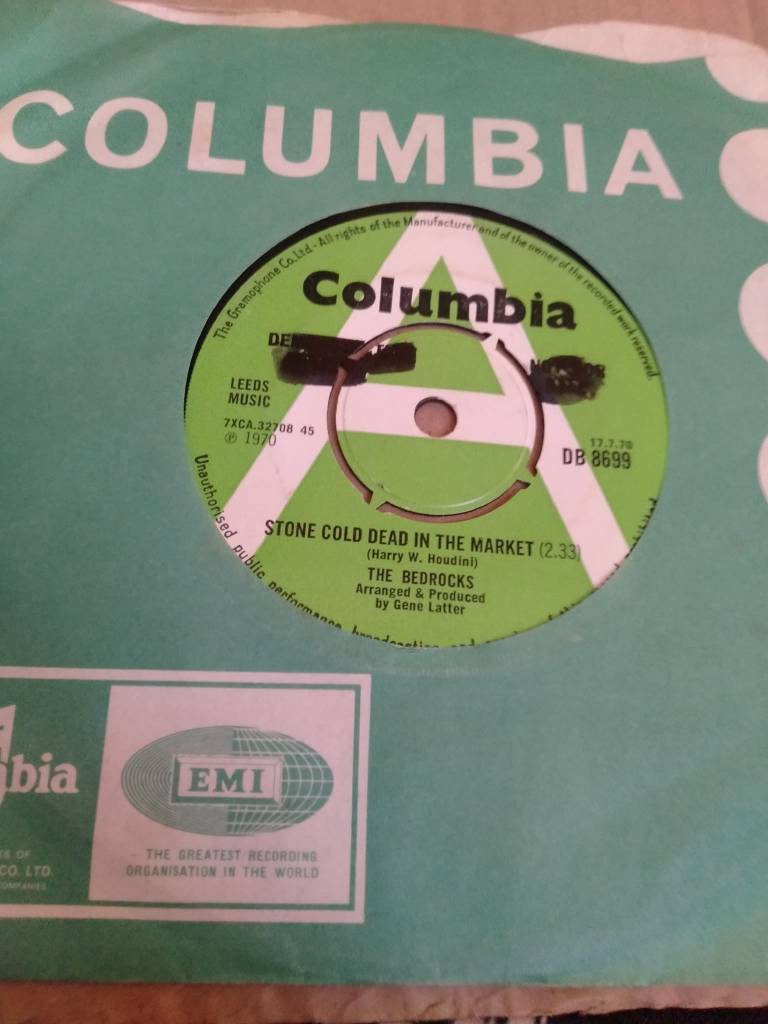

During the first half of the 1960s White singers from Leeds recorded Calypso-inspired songs. Among them were Marion Ryan, Diana Coupland, and Ronnie Hilton. It wasn’t until 1970 that a Black group from Leeds, The Bedrocks, recorded the calypso song ‘Stone Cold Dead In The Market’, re-arranged as a ska song. Local calypsonians such as Lord Prinze (Lionell Hewitt) and Lord Silkie (Artie Davis) were performing in Leeds from the mid-1960s. In 1967 the first Leeds West Indian Carnival included a Calypso King contest which was won by Lord Silkie with his self-composed song ‘St. Kitts is My Borning Land’.

A recording of Lord Silkie performing his 1967 calypso ‘St. Kitts is My Borning Land’, recorded at the Leeds West Indian Carnival in 2017

Another Caribbean musical instrument linked with carnival, the steel pan, was developed in Trinidad during the 1930s and 1940s. The steel pans were first performed in England in the early 1950s. The Trinidad All-Steel Percussion Orchestra (TASPO), fresh from the Festival of Britain, were the first steel band to perform in Leeds in 1951. Other bands visited Leeds during the 1950s and 1960s including Russ Henderson and his Steel Band in 1955. By 1958 Leeds had its own steel band, The Caribbean All Steel Band. More steel bands formed in Leeds during the 1960s including the Esso Steel Band who performed regularly around Leeds. The Caribbean All Steel Band made an appearance on the TV talent show Opportunity Knocks in 1965 and regular dances for West Indians, featuring steel pan music, were held at the Leeds Town Hall during the early 1960s. As well as a steel pan contest, held at the Leeds Town Hall, the first Leeds West Indian Carnival included steel bands as part of its procession. The Gay Carnival Steel Band, formed especially for the carnival, and the Invaders, both from Leeds, were among the steel bands that performed at the first carnival.

Masquerade and Outdoor Procession

European carnivals have a long history in England. As early as 1817 the stage play ‘A Grand Masquerade’ was performed in Leeds. It featured songs, dancing and masks. By the early 20th Century, European carnivals were being held in Bramley, Morley, Wetherby, and Yeadon. In 1928 a European carnival was first held in Chapel Allerton and between 1936 and 1939 European carnivals were held in Harehills. A Grand Carnival Ball was held in Chapeltown in 1925 and Carnival themed dances were held regularly in Chapeltown throughout 1936 and 1937. While many of these events included music, masquerade, dance and outdoor procession they followed European traditions rather than Caribbean ones. Furthermore, the costumes used in these carnivals often depicted racist stereotypes of Black people and other people of colour.

The earliest documented evidence of people of Caribbean heritage combining music, masquerade, and dance in an outdoor performance in Leeds dates to the mid-1920s. During 1924 and 1925 the multi-racial Walton family of Leeds sang, danced and played music on the streets of Leeds while wearing carnival costumes. These street performances became well-known in Leeds. It was the closest Leeds came to having a Caribbean carnival prior to 1966. A Caribbean Carnival Night was held at the Gaumont Ballroom in Bradford as early as 1953 but it wasn’t until 1966 that an indoor Caribbean Carnival Fete was held at Kitson College of Technology in Leeds. Organised by two Caribbean students, Frankie Davis and Tony Lewis, the fete included a live performance by the Jamaican band Jimmy James and the Vagabonds. Marlene Samlalsingh, a Trinidadian student, organised a troupe of masqueraders in traditional Trinidadian costumes. A small outdoor procession took place between Kitson College and the British Council’s International House, off North Street. This was the first outdoor procession in Leeds that included Black people in traditional Caribbean masquerade costumes.

Black people have been involved in tailoring in West Yorkshire since at least the early 20th Century. A Jamaican woman named Ellen Stone was living in Leeds before 1901. She was employed as a tailoress, making men’s suits. George B. Biney from Ghana, was a self-employed tailor living and working in Bradford by 1921. By 1949 another Black tailor, Jamaican man Leslie Broadley, was living in Leeds. During the 1950s and 1960s many Caribbean women found employment at Burton’s tailoring factory in Harehills. Some of the first costume designers and costume makers for the Leeds West Indian Carnival were employed at Burton’s. Among them was Gloria Pemberton who is considered the ‘mother of carnival’. Although traditional Caribbean carnival costumes can not be considered wearable fashion, one Jamaican student in Leeds is also worth mentioning. Rosemary MacDonald held a Jamaican fashion show at the Clothing Department of the Leeds College of Technology in 1956. The outfits she made were inspired by the Caribbean and carried such names as Calypso and Misty Caribbean. Another honourable mention should go to Marlene Burke who, in 1950, was crowned the city’s first ‘Jamaican’ Beauty Queen. Even though the Yorkshire Evening Post called her “a Jamaican girl”, she was in fact Anglo-Indian.

A number of costumed troupes took part in the first Leeds West Indian Carnival but special mention should be given to the ‘Cheyenne Indians’ troupe that later became known as the AAA Team, Europe’s longest running carnival troupe. The troupe included carnival pioneers Arthur France, Ian Charles, Calvin Beach, Rasheeda Robinson, and Gloria Pemberton. Five Carnival Queen costumes were also made for the 1967 Leeds West Indian Carnival. The winning Carnival Queen costume, called the Sun Goddess, was designed by Veronica and Irwin Samlalsingh and was worn by Vicky Cielto.

Emancipation Celebrations

The Leeds West Indian Carnival, first held on 7th August 1967, was the first time in Europe that all the key components of Caribbean carnival were combined. Staying true to its Trinidadian roots, the Leeds West Indian Carnival also acted as a celebration of emancipation. Emancipation was first celebrated in Leeds in 1834. On 1st August 1834 several places of worship held thanksgiving services and prayer meetings. In the evening a public meeting was held at the Queen Street Chapel and funds were raised to present people in the Caribbean with a copy of the New Testament and a copy of the Psalms. The anniversary of Emancipation Day was occasionally noted by the local press. In 1837 the Leeds Mercury noted:

Tuesday was the anniversary of a day most acceptable to the friends of humanity and highly creditable to the national character, the emancipation of slaves in 1834. It will be a memorable day in the brightest pages of the history of Great Britain.

Celebrations of emancipation in Leeds during the 19th Century seem to be few and far between. However, public meetings to mark anniversaries were noted in Liverpool, Manchester and London. At one Emancipation Day celebration in Leeds, organised by the Leeds Young Men’s Anti-Slavery Society in 1861, several Black Canadian reverends addressed a large crowd gathered inside the Music Hall on Albion Street. On occasion, the anniversary of emancipation was marked outside of August. In January 1935 Dr Offor spoke at the Y.M.C.A Luncheon Club on “The anniversary of the Slavery Emancipation Act”.

Emancipation Day services began being held at the Roscoe Place Methodist Church in Chapeltown in the 1960s. A special Emancipation Day service was held at the church in 1966. Conducted by the Rev. Gerald Bostock, the service was broadcast live on the BBC One programme ‘Morning Service’. In more recent years Roscoe Methodist Church in Chapeltown has held annual Emancipation Day services close to 1st August. These services are well attended and offer the local community an opportunity to reflect and remember the victims of slavery. The Leeds West Indian Carnival, held at the end of the month, provides an opportunity to celebrate the end of slavery in the British Caribbean.

In 2007, to mark the 200th anniversary of the Slave Trade Act 1807, a Emancipation Day services was held at St Aidan’s Church in Harehills. The following year Sung Fest, an evening of African music, was held at Space@Hillcrest in Chapeltown to mark Emancipation Day. Heritage Corner’s special Emancipation Day Black History Walk is another annual event that allows its participants to reflect upon the period of slavery in the Caribbean and its links to Yorkshire.

One of those links is John Lewis, an enslaved Jamaican who was recorded as being at the Leeds Parish Church in 1708. 315 years on, on 1st August 2023, sunflowers were placed outside the church in his memory.

Danny Friar recently contributed the chapter ‘Music of the Leeds West Indian Carnival’ to the book Popular music in Leeds: Histories, Heritage, People and Places (2023)

See also:

- Leeds Bi-Centenary Transformation Project: About the Project, 2007 – 2009 – Leeds Bi-Centenary Transformation Project (2009)

- Pan: The Steelband Movement in Britain – Dr Geraldine Connor (2011)

- Celebrate! : 50 Years of Leeds West Indian Carnival – Farrar, Smith, Farrar (2017)

- Before Windrush: Black People in Leeds & Bradford: 1708 – 1948 – Danny Friar (2021)

- Speaking Truth to Power: The Life and Times of an African Caribbean British Man: The Authorised Biography of Arthur France, MBE – Max Farrar (2022)