We mark Black History Month 2024 by welcoming back regular guest author Danny Friar, who has unearthed some fascinating examples of Black History in Leeds in a important piece of research…

Searching for local Black history can often be challenging. There’s no easy way to do it. I find a snippet here and a snippet there and have to try and piece them together. You may not think that the Leodis photographic archive has many photographs that relate to local Black history but recently I’ve been doing a deep dive into this fantastic archive and I’ve managed to discover over 250 images that show Black people going back to the late 19th Century.

There are many photographs that show Black people in the foreground as the main subject of the photo but there’s also plenty of photographs where Black people are part of a crowd or in the background of the photo. There’s a lot of photos of annual events like the Leeds West Indian Carnival and the Reggae Concerts held at Potternewton Park. There’s also photographs that show everyday life; children playing, people at work or doing their shopping at Kirkgate market. The archive also includes photographs of special occasions, like visits to Leeds by Queen Elizabeth II, King Charles III and Nelson Mandela, where Black people were present. There’s also photographs of well-known Black people like Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Louis Armstrong, Albert Johanneson, Tippa Irie and Mel B. In this blog post I wanted to look at five photos from the archive more closely and try to discover what they can teach us about our local Black history.

The first photograph I want to talk about is perhaps the oldest photograph in the Leodis archive that features a Black person. It’s also the least obvious example because not only is the Black person not the subject of the photo, they are so far in the background that it’s difficult to even see them. Photo 1, taken in 1894, shows the construction of the South Leeds Junction Railway. Standing above the area where the work is being carried out is a group of people. Among them is an African prince, Prince Ademuyiwa Haastrup of Lagos. Prince Ademuyiwa visited England in 1894 and spent a couple of days in Leeds in September. He attended services and missionary meetings at the Wesley Chapel on Meadow Lane where he attracted a large crowd that came to hear him speak. He also visited a number of places in the city including a school and the Leeds Town Hall. The photograph of him visiting the construction of the South Leeds Junction Railway is dated to 9th October 1894 but it seems more likely to have been taken on 10th September. It’s a shame the Leodis archive doesn’t have a better picture of Prince Ademuyiwa. Another photograph taken around 1893 shows that he was truly a flamboyant and glamorous prince, decked out in fine clothes and a large gold crown. When he visited Leeds in September 1894 the Leeds Mercury mentioned he was “attired in his gorgeous robes”. Prince Ademuyiwa’s visit to Leeds wasn’t simply for pleasure, he used his position to gain a platform and in an interview with the Leeds Mercury he was able to speak out about the negative effect British colonialism was having on Nigeria. He said:

though we have so much in the way of natural resources, the country is poor, because people cannot acquire them.

Prince Ademuyiwa particularly spoke about the palm oil industry, which Leeds greatly benefited from. Palm oil was a key ingredient in soap making, an industry that made Leeds men like Joseph Watson large profits. Prince Ademuyiwa pointed out that in Lagos enslaved people were being used in the palm oil industry. Despite the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 ending slavery in most of the British Empire, slavery continued in what were to become Britain’s African colonies long after 1834. Lagos was annexed by Britain in 1861 with the remainder of modern-day Nigeria being seized in 1886.

The second photograph is dated to just a few years later, 1899, and is perhaps the oldest photograph in the Leodis archive that shows a Black resident of Leeds. The photo was taken during an official enquiry into Leeds’s insanitary areas. It shows a group of children lined up against a wall, an inspector in a bowler hat and two people standing in a doorway. One is a White woman and the other appears to be a Black man. There is one major problem with this photo; I’m not entirely sure if the man in the doorway is in fact Black. It’s often difficult to tell with old photographs like this one but it is possible. We know of a number of Black people who lived in Leeds during the 1890s. For example, we know of George ‘Bertie’ Robinson who was employed as a footman at Harewood House from 1893. We also know of Eliza Gray, a domestic servant employed by Rev. Charles Lemoine around 1894. A few years before this photo was taken Leeds was home to the African-American singer Thomas Rutling who had come to England as part of the Fisk Jubilee Singers and after their 1877 tour ended he settled in the north of England. He lived in Leeds between 1895 and 1896 but later moved to Manchester. He published his autobiography in Bradford in 1907 and died in Harrogate in 1915.

We may never know the identity of the man in this photo. We can’t even be certain that he was Black. However, there is one Black resident of 1890s Leeds that comes to mind when I look at this photo. Joseph Downie was born in Jamaica around 1862 and came to England in the late 1870s or early 1880s. He was employed at the Leeds Steel Works and in 1890 he married a White woman named Alice Midgley at the Hunslet Parish Church. The couple had two daughters together, Maud and Minnie, and a son who died in infancy. The Downie family lived in Hunslet, first in Organ Yard and later in Beza Street. A booklet titled Hypnotic Leeds was published in 1894 and it provides some insight into working-class life in late-Victorian Hunslet. It describes how children played around the ashpits in the streets. The booklet’s author, Joseph Clayton, describes the ashpits as “the resting place for decayed vegetable matter, and domestic refuse generally” that were “poison to the children who play around them”. This was certainly an insanitary area of Leeds. Joseph Downie died in an accident at the Leeds Steel Work in December 1897, shortly before this photo was taken.

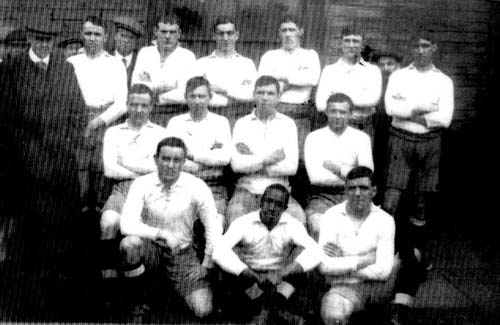

Like the man in the 1899 photo, so many of the Black people who appear in photographs in the Leodis archives have not been identified. However, one that has is the African-American rugby league player Lucius Banks. He can be seen in the front row of this team photo from 1912. Lucius Banks was born in Virginia in 1886 and grew up in Massachusetts. At the age of 20 he joined the U.S. Cavalry and served with them for six years. He was stationed in New York and was said to have excelled at American football and cricket. In 1912 he was spotted playing American football and was bought out of the army by a member of Hunslet’s management committee. He played for the Hunslet Rugby League Football Club as a three-quarter back, the team’s first Black player. He played for the team throughout 1912 but despite scoring a try in his first game, he played most of his games in reserves. He returned to America in December 1912 and the Yorkshire Evening Post reported that he was leaving many friends behind. Back in America, Lucius Banks rejoined the U.S. Army and during the First World War he served in France. After the war he settled in Massachusetts, Boston and in 1919 he joined the local police force. He served with the Boston Police Force until his retirement in 1944. He died in 1955 aged 68.

Another Black man that can easily be identified is Bob Barclay. The Leodis archive contains three photographs of Bob Barclay. This one was taken by photographer Terry Cryer in 1955 and shows Bob Barclay with his instrument of choice, the tuba. Bob Barclay was a master of his instrument and during his career he became known as King Tuba. Bob Barclay was born in Scotland in 1911 to a Scottish mother and a West Indian father. The Barclay family lived in various parts of Scotland and England in the early 20th Century but by 1918 they were living in Yorkshire. By 1946 Bob Barclay was living in the cellar of a house near the city centre of Leeds and was employed as a sheet metal worker. He began his music career in a brass band but by 1949 he had moved on to play jazz and was one of a small number of Black British jazz musicians performing during this period. His band, the Yorkshire Jazz Band played regularly around Leeds and Bob owned his own jazz club, Studio 20 on New Briggate. It was at Studio 20 that Terry Cryer took this photo. The Yorkshire Jazz Band began their recording career in 1949, making Bob Barclay the first Black musician from Leeds to record. The Yorkshire Jazz Band released a number of records throughout the 1950s. A few years after this photo was taken, in 1961, Bob Barclay and the Yorkshire Jazz Band performed a couple of gigs at the Cavern Club in Liverpool, sharing the stage with The Beatles on both occasions. The Yorkshire Jazz Band performed together into the early 1960s. They reunited in 1989 for their 40th anniversary but unfortunately Bob Barclay had passed away a few years earlier in 1987.

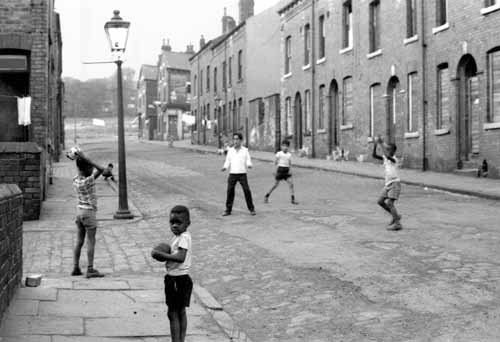

The last photograph from the Leodis archive that I want to talk about was taken in Burley in 1969. It’s a very simple photo that shows a group of children playing football in the street. We don’t know their names or their stories but I chose this photo because it shows both Black and White children playing together. There are many other photos like this in the Leodis archive but I chose this particular one because it was taken in Burley in 1969. The year 1969 was a particularly rough year for people of colour living in Leeds. Despite the Race Relations Act 1968, Black and Asian people still faced discrimination in Leeds and the Fforde Grene Pub on Roundhay Road refused to serve people of colour. 1969 was also the year the Nigerian man David Oluwale was found dead in the River Aire. For years he had been a victim of police brutality in Leeds. The fascist group the National Front had set up a headquarters in Leeds in 1967 and in 1969 racists and supporters of the National Front began riots in the streets of Burley that lasted for two nights. These riots mainly targeted South Asian residents but Black residents were also victims of the violent mob. What this photo shows is, despite the hate, the violence and fear, there was hope for the future. Fifty-five years later when fascists once again turned up in Leeds, they found themselves outnumbered by anti-racists and left after a few hours. Unlike other parts of the country, Leeds didn’t see any far-right riots in 2024. I can’t help but wonder if any of the children in this photo were on the opposing side.