This week on the Secret Library we are delighted to hear once again from Andy Armstrong, one of our heritage volunteers, on a significant piece of cataloguing work we’ve asked them to help us with. You can find more articles about the history of Leeds Libraries elsewhere on the blog…

Hi. My name’s Andy Armstrong and I have taken on the task of sifting through 200 years of Leeds City Council papers held by the Central Library to bring some structure to them and to produce a research guide. I have previously produced guides on Transport, Health, Housing and now I’ve completed a new guide about the history of Leeds City Libraries.

This blog covers the main issues that are highlighted in the new guide and I have added at the end some extracts from the various papers, for example the Libraries Committee reports from 1868 onwards, that give a bit more flavour to life in the libraries.

Leeds City Council (then called Leeds Corporation) became a local authority as we know today following the Municipal Corporations Act 1835. At that time, the only libraries were private, with some accessible by subscription. It wasn’t until the 1850 Libraries Act that local authorities were given the power to set up public libraries. An initial vote in 1861 rejected the proposal to set one up in Leeds, primarily because of the additional cost to ratepayers. A second vote in 1868 was narrowly passed when the costs were seen to be outweighed by the benefits of encouraging the working class to spend more time reading and learning and less time drinking in pubs.

This sense of betterment was an abiding theme throughout the 19th century, and statistics were collected for many years identifying the occupations of borrowers alongside the type of books they were reading. By 1944 it was noted that professional people made more use of the library than the working classes.

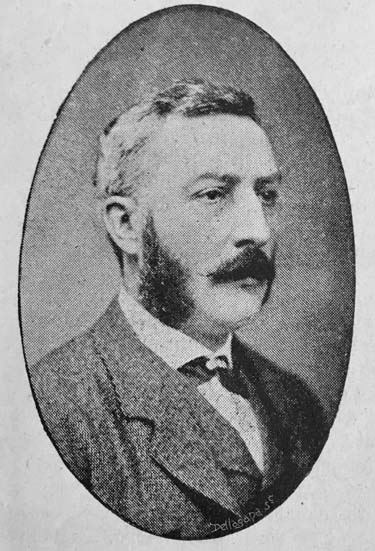

In 1870 James Yates was appointed as our first Chief Librarian followed by branches opening in the Hunslet Mechanics Institute and the Holbeck & New Wortley Zion School, Whitehall Road later that year. Local libraries remain a central plank of the service with 37 branches currently in use.

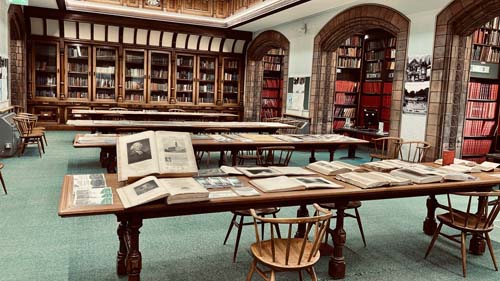

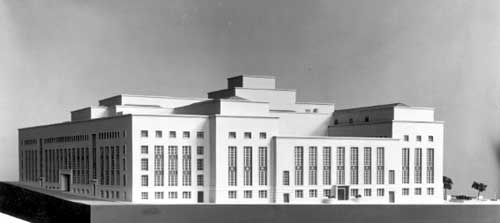

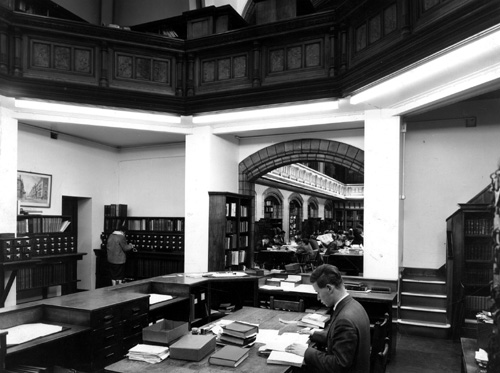

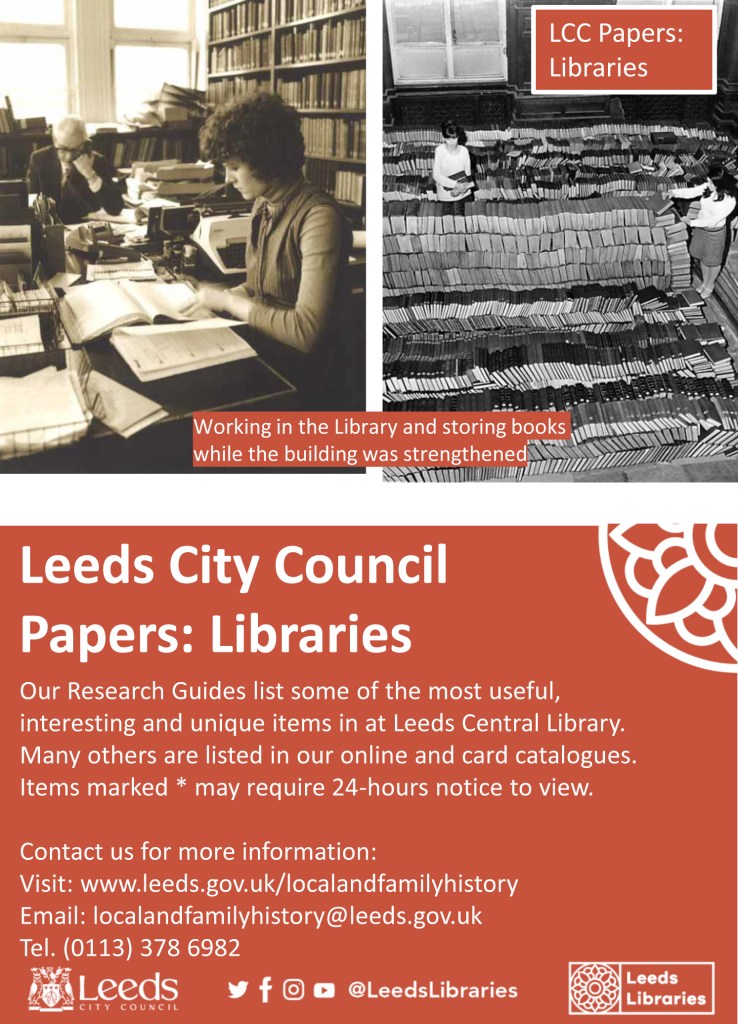

The Municipal Building opened in 1884 as a joint site for expanding Council services and a Central Library. From those early days, the Municipal Building was not an ideal building for hosting the library, and a long-standing campaign for better premises was close to being approved in the 1930s, but the imminent war meant that plans were dropped. The findings in the 1960s that the old building could not support the weight of all the books led to a major strengthening project that took 5 years to complete.

Recruitment has been a long-standing issue for the library. For example, in 1899, the Library Committee reported

The difficulties which have been experienced in obtaining suitable male assistants to fill the vacancies in the staff have induced the Committee to try the experiment of throwing the employment open to persons of both sexes. Female assistants are now engaged, and they have been found suited to the employment.

After the Second World War, shortages of staff became a major issue for the libraries. Turnover of staff was routinely a third every year, which led to many issues around training and recruitment. The difficulty of recruiting clerks to undertake routine duties alongside awkward hours, led to the Council looking at how computerisation could help address some of these issues as early as 1970.

The number of books borrowed per year rose throughout the 19th century and reached 1m by the turn of the 20th century. Numbers continued to rise, reaching a peak of 5.5m in the early 1970s, but have fallen to less than 2m today.

From the 1970s onwards, Leeds Libraries have had numerous strategic reviews and now aligns with the Universal Libraries Offers which focuses on Culture & Creativity, Health & Wellbeing, Information & Digital as well as the traditional Reading. This has provided a good opportunity to give better access to the many heritage collections held in Leeds.

The papers include the more routine issues dealt with on a day to day basis and also the changing world since the first library was opened. Here are some extracts:

1899. “The difficulties which have been experienced in obtaining suitable male assistants to fill the vacancies in the staff have induced the Committee to try the experiment of throwing the employment open to persons of both sexes. Female assistants are now engaged, and they have been found suited to the employment.”

1909. The statistics are important for “showing the number and character of the books used, the social status of those who use them, and the great extent of the works of the Libraries.”

1931. Staff instructions: 1. Hands to be disinfected twice a day using the Deodar hand spray. 2. Audible conversations not permitted. 3. Staff must keep work diaries which are to be signed off every week. 4. Sick pay is 3/6 of full pay for less than 5 years of service. 5. Books borrowed from households where notifiable infections are present must be seized by the Public Health Authority for disinfection. 6. Janitors holidays – 4 bank holidays plus 6 days.

Included is a report to show how Leeds compared with the national standards. All good with one exception – women with qualifications were not paid a similar rate to men doing similar work.

1938. Includes details of the proposed new Central Library, Art Gallery and Museum, due to be built in stages on the existing site.

1944. Survey still focussed on helping the working classes – only to find that (from the only 20% who responded) that proportionally, professional people made far more use of the library than the working classes.

1948. “During the year there have been 43 resignations from a staff numbering 126. This has not been conducive to efficiency.”

1950. Staff turnover is a consistent gripe. “Whilst it will be agreed that all assistants should have an opportunity of gaining experience in the Reference Library, yet it should also be appreciated that the department exists to serve the public and not the staff.”

1954. More postal enquiries, some of which are “based on an easy and mistaken assumption that the library will do the work for the enquirer.”

1961. “The difficulty of obtaining books is the main reason why some students, whose ethical standards are poor, take books away without permission.”

1964. “Because so many senior staff have resigned in despair the staff association has collapsed and the lack of any social and professional contact does not make for a happy team.” Seniors are paid below national averages, few graded posts mean progression options are limited, working conditions are poor, there are no social facilities and there is no apparent interest by the Committee.

1966. Large numbers of Pakistani and West Indian children now use the Sheepscar Junior Library and are, according to the branch librarian, among the best behaved and cleanest users.

1970. A report into the difficulty of recruiting clerks to undertake routine duties alongside awkward hours (& no doubt poor pay) and how computerisation will help.

Fascinating stuff and great work!