The latest in an occasionally-regular series exploring books and other items selected from our vast collections. In this entry Librarian Antony Ramm looks at a slim 18th-century volume of antiquarian musings…

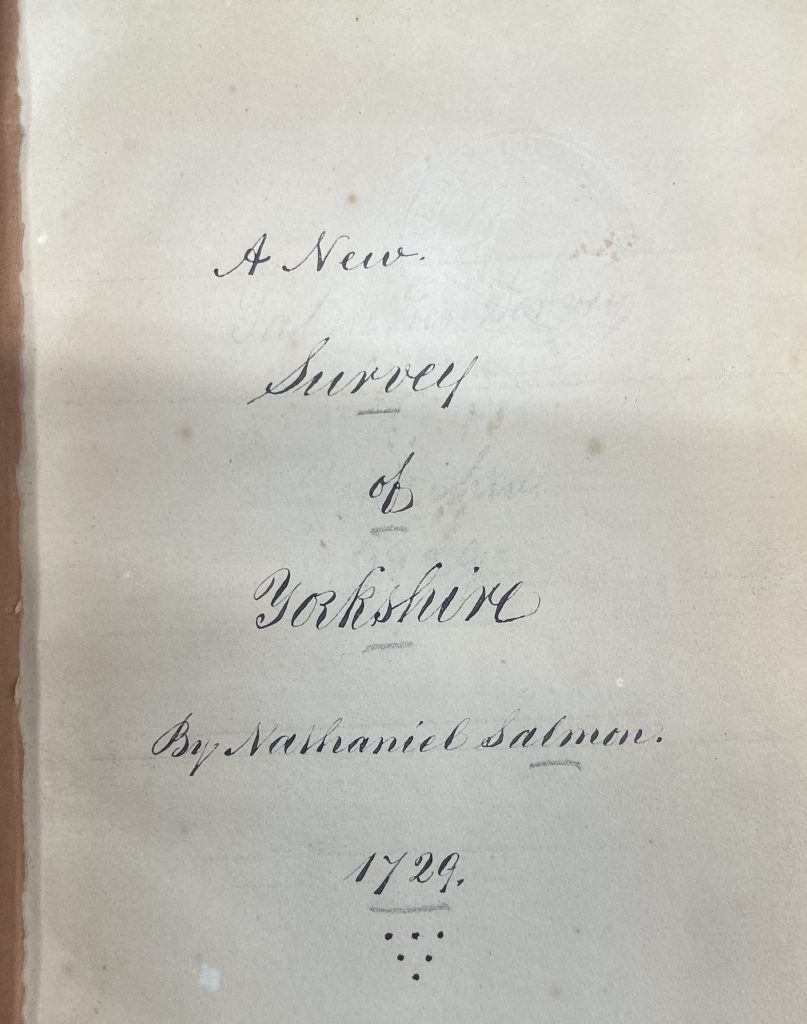

Titled ‘A Survey of Yorkshire,’ it is debatable, really, whether this is even a book at all: although bound like a book, it is quite clearly a chapter, one that is (as our catalogue entry makes clear) extracted from Nathaniel Salmon’s A New Survey of England (1728 – 1729). Our version consists only of pages 555 – 587 of A New Survey. Why this chapter was extracted, by whom, and how it found its way into our Central Library Special Collections is, at present, unknown.

Either way, it is a frustrating read. Stymied to some extent by the antiquated writing style, it’s also just generally unclear what Salmon is attempting to achieve here. He appears to be tracing evidence of the Roman occupation of Britain through the etymology of place names and, in particular, a comparative analysis with the relevant sections of the Antonine Itinerary Iter Britanniarum (a register of the stations and distances along various roads in the Roman Empire) to trace “three Roman military ways from the North of England to the South.”

In this Salmon was following “the romanising tendencies in antiquarianism in the 1720s and 1730s.” (Rosemary Sweet, Antiquaries: The Discovery of the Past in Eighteenth-Century Britain, p. 170). Salmon is described by Rosemary Sweet as

[the] author of a history of Hertfordshire and collections for a history of Essex, [and] also a prolific writer upon Roman antiquities, although his researches drew heavily upon Camden, and lacked the depth of Horsley. Salmon’s mainstay, as with Pointer, was coins, camps and roads. The identification of the various itinera he offered is easily faulted now, and his etymologies can be shown to be largely spurious, but what is interesting is that he explicitly identified himself with a new tradition in Romano-British antiquarian scholarship which attached singular importance to observation and field work… (Sweet, Antiquaries, p. 170 – 171)

So, an important enough figure and one whose books are certainly worth preserving as part of an antiquarian tradition which included the first historical writings about Leeds. Sadly Salmon’s book doesn’t really include Leeds itself, at least not beyond brief references to Alwoodley, Wetherby and, slightly further afield, Castleford. At least I don’t think it does – it’s sometimes hard to tell exactly what Salmon is writing about, certainly to a non-expert and 300-years later.

All of this is, for sure, made more difficult by the fact we only have one short chapter from the whole work. No doubt even the full volume would be to some extent opaque for modern readers, but it would at least provide some context. The extracted, partial nature of the text points as well to something we are conscious of in our library collections: preserving not just material in-and-of-itself but also the context of that material – so, for instance, archiving the whole of a magazine and not only the specific article we’re interested in. That’s something that would, perhaps, have been useful in Salmon’s case – the chapter on its own is interesting, certainly as an example of the 18th century antiquarian tradition described by Sweet, but retaining that material in its place in Salmon’s entire book would have aided the reader’s sense of what exactly it was the author was attempting to achieve and convey.

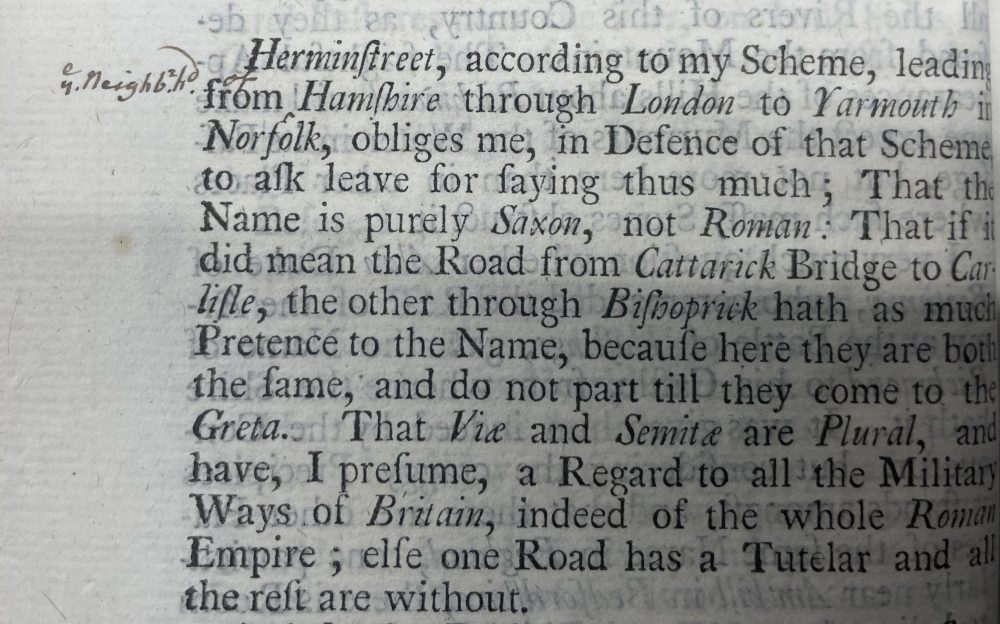

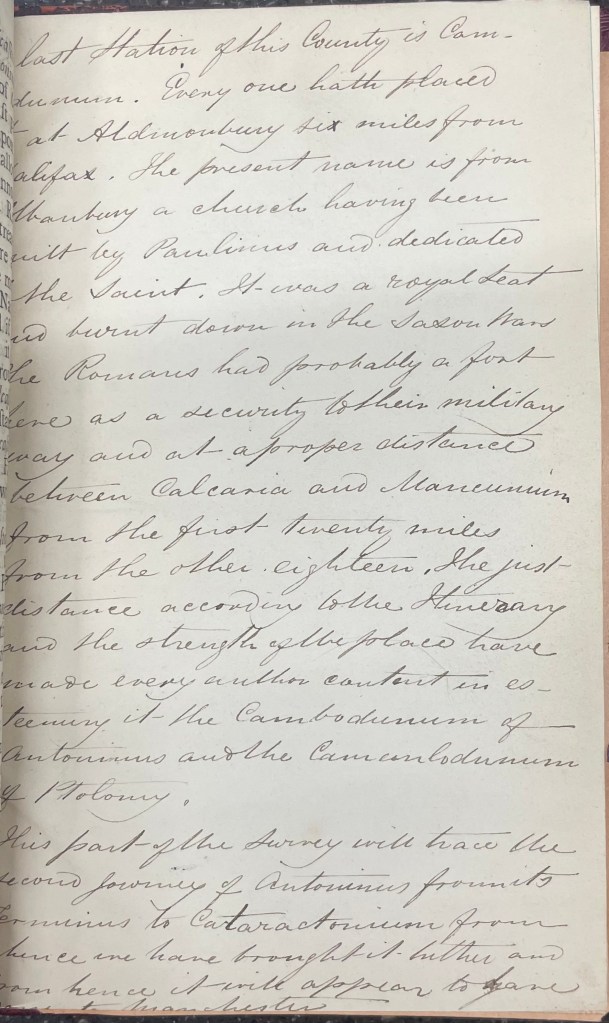

Even a sense of who the book belonged to prior to its accession into our collections might have provided some clues. And there are a few very small clues as to the book and chapter’s usage. The title page has been clearly handwritten, perhaps by the owner who extracted it from its original text and, behind that writing, can be faintly seen some earlier writing, tantalisingly unreadable at this remove. Then, on page 568, can be seen the only annotation or correction made across the text: someone – presumably, again, the text’s owner – has inserted into the margin the word ‘neighbourhood’.

Finally, the final page of the chapter is, in fact, missing entirely and has been replaced with a handwritten transcription of – we can only assume, with no other edition of the text to compare it to – the missing text. Who wrote this transcription is, unfortunately, unknown at the present stage. That’s as far as we can go with the book’s provenance: where we acquired it from, who any earlier owners may have been and, crucially, why they chose to retain only the chapter relating to Yorkshire. The book is, to steal a phrase from an entirely unrelated source, ‘a study in frustration‘.

Do get in touch if you can tell us anything about this slice of 18th-century history.

I imagine the library has a copy (or access to) Turville-Petre & Gelling (Eds) Studies in Honour of Kenneth Cameron, Leeds Studies in English, no. 18 (1987). Ken taught in Sheffield and Nottingham Unis and was an expert in English place names especially Norse. He had a special interest in NE England. His work my throw some light on your volume.

Thank you very much! We do have the Leeds Studies in English series in our collection so we’ll be investigating this recommendation soon.

Best wishes

Antony

Leeds Libraries

Ken was a larger-than-life character! I knew him as we were both part of a motley Friday after work drink group! He was a wonderful raconteur.