This week, as part of Local and Community History Month, we welcome guest author Janice Heppenstall for a fascinating and in-depth look at using electoral results in family history research…

Janice will be joining us at the Central Library on Thursday May 11 to deliver a talk based on her family history research. Further information and tickets can be found on our Ticketsource page.

As we take our genealogical research further back in time, we get much more from the records we find if we can place them in context. This means that through reading and developing our knowledge and understanding of local, social and political history we can better understand our ancestors’ lives. This is a post about Poll Books, and how we can use them in genealogy; but it also aims to highlight overlaps between family research and wider historical reading, including specifically the history of polling for Leeds residents.

First, what are Poll Books?

In 1696 Parliament legislated to make County Sheriffs, Mayors, etc responsible for recording the poll within their areas, including “the names of each freeholder and the place of his freehold and for whom he shall poll.” They had to provide a copy of this information for a reasonable charge to anyone requesting it. The resulting printed Poll Books, prepared after each Parliamentary election, record the name of every elector who voted, their parish, township or (later) street of residence, and until 1868, the location of the property that qualified them for the vote. Poll Books may be arranged alphabetically by surname, by parish/ township, by the order in which votes were cast or even divided into booklets containing only those who voted for individual candidates. The publication of Poll Books became a commercial venture, and you may find copies by rival local printers covering the same election.

From 1832, Poll Books existed alongside Electoral Registers which recorded all men who were entitled to vote. These may well include names not found in the Poll Books – men who had the right to vote but didn’t exercise it. After 1872, when the ‘Secret Ballot’ was introduced, Poll Books were superfluous: all legally required information could be found on the Electoral Registers. Hence, the period for which we might find Poll Books to help in our genealogical research is 1696 to 1872.

Names, locations and years are the nuts and bolts of genealogical research. However, with a little knowledge about the historical development of suffrage, the very presence of our ancestor in a Poll Book at any particular point in time provides additional information about their social and financial standing and their political affiliations. Yet although electoral records from before 1696 rarely survive, to understand the rules behind who had the right to vote we need to go back to the thirteenth century…

A very brief history of Parliament

Parliament has sat at Westminster since the 1230s. It was where men of wealth and influence debated national affairs, took decisions regarding war, heard legal cases at the highest level and granted or refused the king’s requests for extraordinary taxation. Originally, those attending were the king’s tenants-in-chief (landed classes) and men of the highest ecclesiastical positions (archbishops, bishops, abbots). However, parliament met only ‘at the king’s pleasure’ – when he wanted something.

During the second half of the thirteenth century there were important developments. First, Parliament began to meet by schedule. Then steps were taken to formalise the attendance in Parliament of select individuals of a lesser status: each county was to elect two knights of the shire to represent its interests in parliament. The shire knights were still prominent landowners (landed gentry or local squires) and their election was only by barons, other knights and significant freeholders. From 1265 certain towns and boroughs were also permitted to elect individuals – burgesses – to represent their towns’ specific interests. These burgesses were wealthy merchants, lawyers or craftsmen. Initially, the attendance of the shire knights and burgesses was only when invited. This became known as ‘the summoning of the Commons’, meaning the common body of the people (although they were hardly that!) as distinguished from those of noble rank. but from 1327 they became a permanent part of Parliament. Since 1341 they have met separately, although it wasn’t until 1544 that the terms ‘House of Lords’ and ‘House of Commons’ were used.

Leeds: from ‘a borough within a manor’ to ‘a borough without representation’

The issue of borough status is of particular importance to any discussion about voting rights in Leeds. A form of borough charter had been in place since 1207, granted by lord of the manor Maurice ‘Paynel’ or ‘de Gant’. The purpose of this had been to free inhabitants from certain manorial restrictions, thereby attracting skilled craftsmen to settle in the borough to practise their trade. Crucially, though, this did not transform the manor into a borough. Rather, it established a borough within the manor, and even then only part of the manor: just the street still known today as Briggate. This arrangement didn’t meet the conditions required for Leeds to be invited to send burgesses to Westminster.

The following four centuries was a period of great expansion for the textile industry in the West Riding. People from surrounding areas were attracted to the parish, and particularly to the township, of Leeds (roughly what’s now the city centre) because of the availability of land and facilities for clothiers. During the first half of the seventeenth century the population increased from around 4,000 to 6,000. This period also coincided with the rise of a group of leading townsmen with personal and public ambitions. It was they who finally achieved a charter of incorporation, granted by Charles I on 13th July 1626. The new royal charter applied to the entire parish of Leeds (which covered 32 square miles and included eleven townships) but unlike the charters of other nearby boroughs, it did not create a Parliamentary Borough: that is, it did not grant the right to elect a Member of Parliament to attend the House of Commons – a crushing blow to the local oligarchy. Representation at Westminster would have given the needs of the town, its businessmen and industries a voice on the national agenda. Apart from a brief period during the Cromwellian parliaments, Leeds would not secure the right to parliamentary representation until 1832. Contrast this with York (charter dating from 1254), Kingston upon Hull (from 1304), Knaresborough, Ripon, Boroughbridge and Thirsk (all from 1553), Aldborough (1558) and Pontefract (1621). This did not mean, of course, that no resident of Leeds had the vote. However, those who did, were casting their votes for just two knights of the shire whose primary remit was to represent the interests of landowners throughout the whole county; and in order to vote, electors had to travel, or send a proxy, to York.

So who had the right to vote?

Here, too, the existence or otherwise of parliamentary borough status made a difference.

For the county franchise (which applied to residents of Leeds and most of Yorkshire) initially, all freeholders had the right to vote. However, by Act of Parliament in 1429 voting rights were restricted to ‘Forty Shilling Freeholders’: owners of freehold land with an annual value of at least 40 shillings. This was a substantial property requirement. This Act remained in force for more than four hundred years with no amendment to the 40 shillings property requirement. Consequently, with natural inflation over four centuries, there was a gradual increase in the enfranchised proportion of the population, and you may see a very slight interest in the number of your ancestors entitled to vote.

The rules for borough franchise were completely different, and in fact varied from town to town according to local custom. In some boroughs (e.g. York) the vote was available to all freemen and very much tied in with the Guilds; in others (e.g. Northampton) all householders could vote. Some (e.g. Pontefract) granted the vote to all burgage holders; others to members of the corporation only, and so on. Being a borough without parliamentary representation Leeds, of course, did not enjoy this freedom to set the rules for which inhabitants could vote.

Estimates vary regarding the size of the electorate during these centuries. Some suggestions are that in 1600 it would have been around 2% of England’s population, around 3% of the UK population by 1780, and about 5% by 1830. In theory, since the qualification was based on property, the vote was available to some women. Certainly most landowners were male, but some unmarried or widowed women held land, and it seems a few did exercise their right to vote. (If you have come across any please do leave a comment!) Hence, the beginning of the road to universal male suffrage brought an end to the opportunities a few women had previously enjoyed.

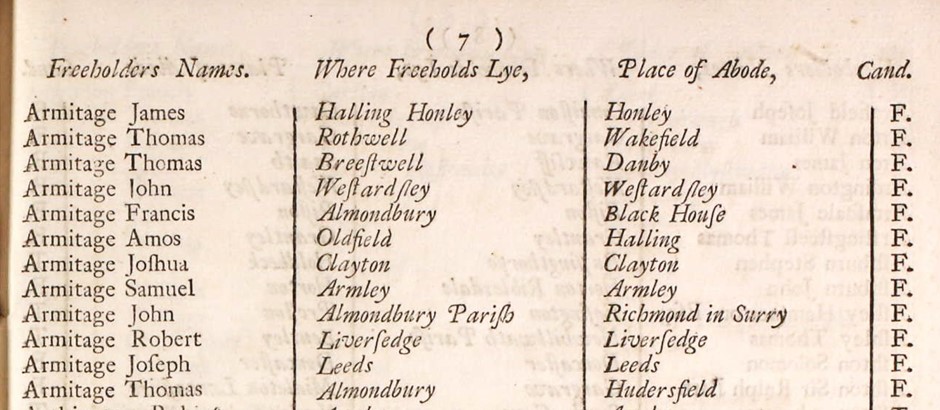

Reading a pre-1832 Poll Book

Based on all of the above we can now get a lot more information from the inclusion of our ancestor in any pre-1832 Poll Book rather than simply names, locations and years.

- We know that simply being a ‘Freeholder’ was not enough. If your ancestor is in a pre-1832 Poll Book his ‘qualifying freehold’ had an annual value of at least 40 shillings.

- He did not necessarily live in the qualifying freehold. Six of those in this extract didn’t. However, the inclusion of John Armitage, resident in Surrey, on the Yorkshire Poll tells us that a qualifying freehold in Yorkshire did not entitle him to vote in Surrey. He had to travel (or send a proxy) to York to exercise his vote. This might mean we have to be prepared to look wider for proof of an ancestor’s right to vote.

- The inclusion of every town, township or village ‘Where Freeholds Lye’ on this 1741 Poll Book for the County of York confirms that these locations are NOT Parliamentary Constituencies. We will not find Poll Books specifically for these locations. Their electors voted only in the Yorkshire county constituency poll.

- The inclusion of Armley as distinct from Leeds indicates that ‘Leeds’ here refers to the township, not the wider parish. If your ancestor lived in Allerton, Armley, Beeston, Bramley, Farnley, Gipton, Headingley, Holbeck, Hunslet and Wortley – the other townships within the ancient parish of Leeds – you need to look for them in those township locations.

- The ‘Cand.’ column tells us how your ancestors cast his vote. The candidates here, Cholmley Turner and George Fox (names given on the front cover) are indicated by an F (popular with these particular electors shown) or a T.

- Through combining this new information with what you already know about your ancestor, you might make some surprising discoveries. This 1741 Poll Book includes several of my own ancestors from the West Riding, amongst them a blacksmith and a butcher – not trades we would today equate with ‘substantial’ properties; but this is a window into the past where master craftsmen and traders played an important role in their towns, and where in any case freehold land was likely inherited.

- Here’s another, as yet unresolved, example from my own research of how Poll Books might help answer questions apparently unrelated to the right to vote. I recently discovered that a 7x great grandfather, Nathaniel, had a number of freehold properties in Woodhouse, Leeds – but did they amount to a ‘Forty Shillings Freehold’? Since he died in 1741 Nathaniel would not be included in this 1741 Poll Book, but finding him on earlier Polls (1715, 1722, 1727, 1734) would evidence a 40 Shilling Freehold. It would also answer another question: Nathaniel had remarried and moved to his second wife’s property near Wakefield, leaving his sons in law to work his Woodhouse lands. The precise location, and indeed the marriage record, have not been located. His entry on any Poll Book would include his abode, which in turn may guide me to the correct marriage register, and thereby the identity of his wife.

The gradual widening of the franchise

The Representation of the People Act, 1832, also known as the Great Reform Act or First Reform Act, made a number of significant changes to the electoral system which impacted significantly on Leeds and surrounding areas. As noted, the number and location of boroughs had long since outlived its usefulness. Great emerging industrial towns, including Leeds (population: 30,000 in 1801) still had no representation at Westminster, while Aldborough (population 484 as of 1821, of which just 64 electors) and Boroughbridge (population 860 in 1821, of which 74 electors) not only each had two members of parliament, but both were ‘pocket boroughs’, controlled by the Duke of Newcastle. The 1832 Act abolished these and most other pocket boroughs. Within the West Riding, constituencies were completely reorganised, resulting in a total of sixteen members of parliament: two for the new ‘county’ constituency of the West Riding itself; two each for Bradford, Halifax, Knaresborough, Leeds, Pontefract, Ripon and Sheffield; and one each for Huddersfield and Wakefield. The boundary of the new parliamentary constituency of Leeds was contiguous with the parish and therefore included all eleven previously mentioned townships.

Alongside this, the Act was the first piece of legislation to expand voting rights throughout the United Kingdom. The goal was to enfranchise the lower middle classes while excluding the working classes. In the counties the franchise was broadened to include men who owned or occupied lands and tenements worth between £2 and £5 per annum, while in the boroughs the franchise was standardised, extending the vote to all owners or tenants of buildings worth at least £10 per annum. Voters had to be over 21 and were specifically defined as ‘male persons’, thereby formally disenfranchising women.

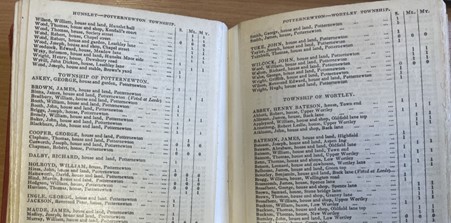

Reading a Poll Book from 1832

- It is suggested that the 1832 Act increased the size of the electorate to around one man in seven, so if your ancestor had the vote he (most definitely not she) remained one of quite a select bunch.

- Remember, though, that this no longer means your ancestor was a freeholder. Borough electors might be owners or tenants, provided the holdings were worth at least £10 per annum.

- You’ll now find these ancestors recorded in Poll Books specifically for Leeds. Electors in the lands surrounding the parliamentary constituency of Leeds will be found in the West Riding constituency Poll Book.

- For Leeds, voters are arranged alphabetically within the township where the qualifying property is located.

- The property qualification is indicated: “house”; “house and land”; “house and shops”, etc. In the extract above we see that for more built-up areas the street is given; otherwise just the township – this might be the earliest mention of a specific street on records for your ancestor.

- A note on page 2 references the Returning Officer as the Mayor, with Deputy Returning Officers for every township, indicating that individuals voted close to where they lived – a huge improvement over having to travel to York.

- It seems there was some flexibility to vote in a different township (e.g. James Binns of Potternewton), perhaps indicating such individuals were not resident at the qualifying property.

- Again, we see our ancestors’ political affiliations. Candidates are Michael Thomas Sadler (Conservative), John Marshall Jr (Whig) and Thomas Babington Macaulay (Whig). They are represented at the top of each page by S (Sadler), ML (Marshall) and MY (Macaulay). Electors could vote for two, and their choice(s) are indicated with a ‘1’.

- In this publication those who did not vote are indicated with a ‘0’. As we know, this was not a requirement but it’s a great help to family historians who can see without having to consult the Electoral Register whether a missing individual had the vote.

In fact fewer of my own ancestors have the vote in 1832 than in 1741, and I suspect some of you will find the same, particularly regarding Leeds ancestors. Industrialisation replaced many fine crafts with factory production, and reduced the status of those doing the work from craftsmen to ‘labourers’ – exactly the men the 1832 Act sought to exclude.

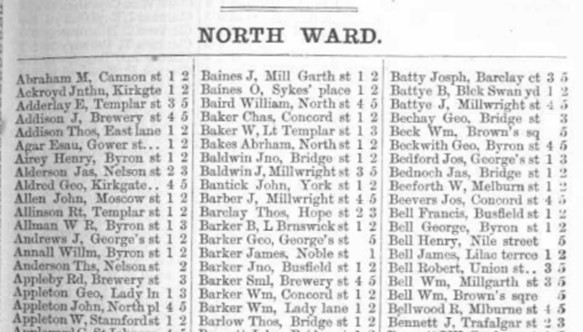

The 1867 Reform Act and the 1868 Poll

The Representation of the People Act of 1867, also known as the second Reform Act, roughly doubled the electorate to almost 2.5 million, many of them urban working men. In the counties the vote was extended to all male copyholder and leaseholders of property valued at £5 or more, together with those who occupied land and paid rent of £12 or more per year. In the boroughs the vote was granted to all male householders (owners and tenants) of dwelling-houses, as well as lodgers paying at least £10 rent per annum. In Leeds, the Act increased representation from two to three MPs.

What did all this mean for our Leeds ancestors?

- We’re now likely to find many more of our male ancestors. The increase in vote is illustrated by the fact that the 1832 Poll Book for Leeds comprises 70 pages. This 1868 edition, with three columns to the page, has 178 pages!

- Although a property qualification remains, this is not mentioned in the Poll Book.

- However, since the property qualification is for owners, tenants and lodgers, you won’t find any adult males who were still living at home, even if they were over 21 and married.

- Unlike in the 1832 Leeds Poll Book, those who had the right to vote but did not use it are not included. If your ancestors are missing, you could confirm if they had the right to vote, and therefore their property status, by consulting the Electoral Register.

- Within the polling districts/divisions, voters are listed in alphabetical order by surname. However, Leeds was divided into 31 polling districts, so finding your ancestor can be difficult, particularly if they tended to move about between adjacent districts, e.g. between Hunslet and Holbeck. Also some districts are sub-divided into two or even three divisions.

- This is our last chance to see our ancestors’ political affiliations. There were five candidates, the two numbers to the right of each voter’s entry indicating his choice:

- Edward Baines (Liberal)

- Robert Meek Carter (Radical Liberal)

- Sir Andrew Fairbairn (Independent Liberal)

- Admiral A. Dumcombe (Conservative)

- William St. James Wheelhouse (Conservative)

Some conclusions

This post has illustrated how much more we can learn about our ancestors by understanding the context of the records we use. Although we have focused on Poll Books, the same would apply to other record types. Equally, we have seen that changes impacting on our ancestors is not purely about electoral reform; the industrial revolution means that some of our ancestors might have a lower social standing than their own forebears. Finally, although Poll Books existed only from 1696 to 1872, the movement towards universal suffrage continued. However, to keep up with our ancestors’ voting rights we have to switch to consulting the Electoral Registers.

Where to find Poll Books

Leeds Local and Family History Library has the following:

Leeds: 1832, 1832-1835, 1841, 1852, 1857, 1859, 1865 and 1868

Yorkshire: 1741, 1807

Yorkshire West Riding: 1817, 1835, 1837, 1841, 1848, 1859, 1865, 1869

(There are also Electoral Registers for 1832, 1836, 1840. 1846, 1847 and then every year from 1849.)

The library also has the following publication, which is a finding guide for Poll Books throughout the country, and includes Poll Books lodged with other libraries and archives throughout Yorkshire and beyond:

Jeremy Gibson and Colin Rogers: Poll Books 1696-1872: A directory to holdings in Great Britain, 1989, Birmingham : Federation of Family History Societies

Leeds Libraries users have free access to commercial genealogy website ancestry.co.uk

You’ll find some Yorkshire Poll Books in the record set UK, Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893 https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/2410/

Or if you’d like to search for Poll Books in other parts of the country go to Search → Card Catalogue and then just type “poll” into the keywords box to see what other sets are available.

*****

Janice Heppenstall is a professional genealogist with a passion for finding the extraordinary in ‘ordinary’ people’s lives, using their stories as a springboard to explore the local, social and political context in which they lived. She has a special interest in Leeds and West Yorkshire, where a large proportion of her ancestors lived. Indeed, over the years she has spent so much time with them she has come to think of them as friends. Janice blogs regularly on family history and genealogy topics at https://englishancestors.blog/ and is also to be found on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/englishancestorsgenealogy

*****

It is clear from your article, Janice, that these sources are very important in tracing ancestry. I think, however, that they have an additional importance: they give an insight into social and structural history. The way the poll books were put together, the insights they give as to the ways the citizenry (and who) could vote says much about the psychosocial constructs those in power had in their heads at various times. The changes in the poll books you outline, have their equivalence in the changes the Boundary Commission implements today.

Yes Stuart I agree, and am very much with you on this. In fact, via the filters of my own and others’ ancestors’ lives and wider reading to place them in social and political context, increasingly I see echoes of the past in current events and political/societal change. I didn’t emphasise this in the piece above, since it was primarily about genealogical uses, but the power and control element is plain to see – and all the more so when you factor in the later women’s suffrage movement and the arguments used to fob them off. Thanks for reading it. Janice

Fascinating post! Thanks for this. I knew so little about the expansion of suffrage , especially pre Victorian times.

Thanks for the feedback Ed, and I’m glad you enjoyed it – Janice