In this blog post Rhian Isaac, Senior Librarian for Special Collections and Heritage, shares a deadly discovery.

One weekend I stumbled upon an intriguing article in National Geographic that highlighted the Winterthur Museum’s Poison Book Project, and it instantly caught my attention. I was captivated with the idea of poisonous books lying undetected in library collections, their brightly coloured bindings hiding a deadly secret! I had often come across poison as plot devices in stories but not real life dangerous books, it all felt very Name of the Rose. I also didn’t think we would have any in our collections at Central Library.

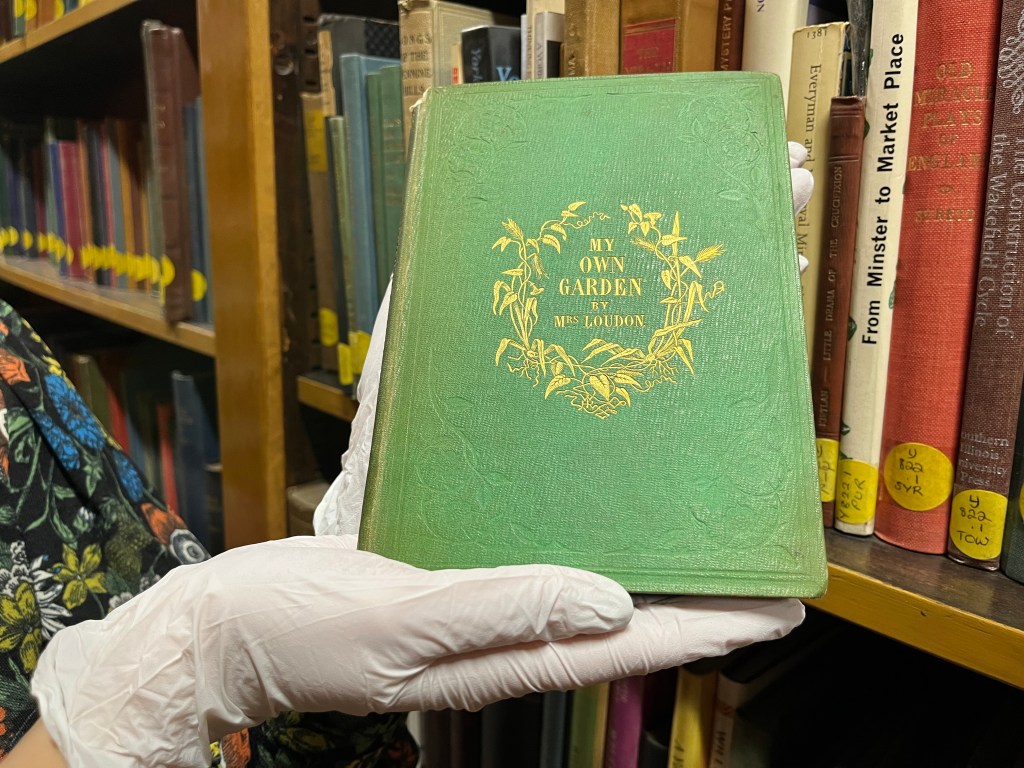

The Poison Book Project was started in 2019 by Melissa Tedone (Head of library materials conservation) and Rosie Grayburn (Head of Scientific Analysis and Research lab) at the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library when they first identified a book containing the green pigment known as Paris green, or emerald green. This pigment, containing toxic arsenic, was popular during the 19th century as it produced a vivid green colour and was used in everything from wallpaper to children’s toys. The researchers at Wintherthur estimate that tens of thousands of books produced between the 1840s and 1860s contain emerald green in their cloth bindings.1 The Poison Book project aims to locate as many of these books as possible and a database of confirmed cases is available to browse. Out of curiosity I cross referenced this list with our library catalogue and found a potential match. However, even if the book shared the same date and title, it could have had a different binding and libraries have often rebound books – so there was no guarantee that our copy would be one of these toxic tomes.

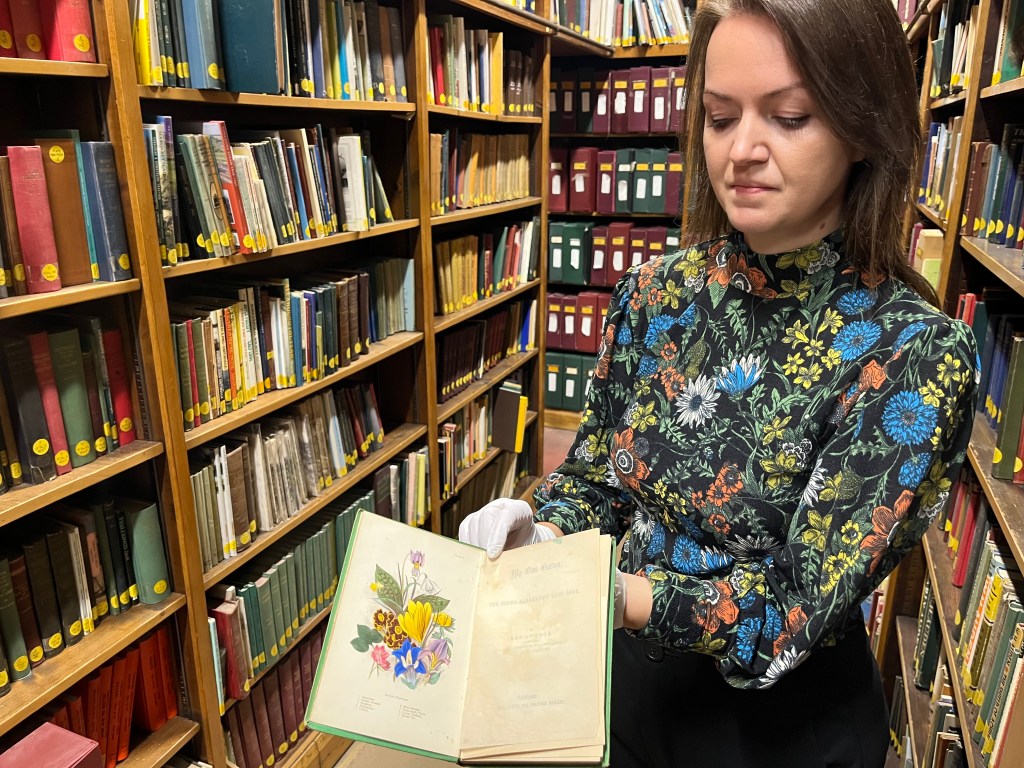

When we carefully pulled the copy from the shelves its bright green colour persuaded us that we may have located an arsenical book. A comparison with one of Winterthur’s special bookmarks convinced us further.

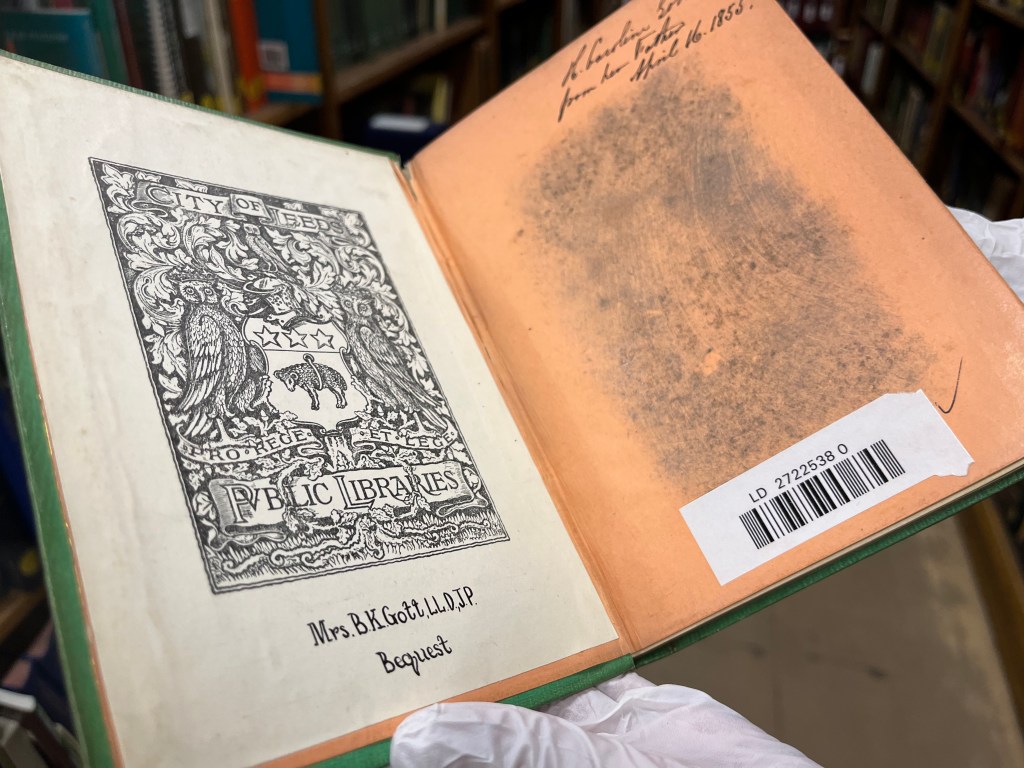

The book was published in 1855 and is called My Own Garden: The Young Gardener’s Yearbook and as its title would suggest contains tips for budding young gardeners. The inscription inside the book’s front cover shows it was a gift unwittingly given to a young Caroline Gott, one of the family of renowned Leeds industrialists, by her father Benjamin in 1855. It became part of the Leeds collection when Beryl Gott left a large part of her own library, mainly early botanical books, to Leeds Public Libraries. A bequest of money from Beryl Gott to purchase horticultural books ensured that important items on this subject continued to be added for the benefit of people in Leeds. You can read more about the Gott Bequest in our other articles and search the collection on the online catalogue.

What next?

You would probably have to eat a whole book containing emerald green to suffer severe arsenic poisoning but touching and ingesting particles could lead to some unpleasant symptoms. My Own Garden now contains a warning on its box and gloves must be worn when handling it. We continue to be on the lookout for suspected arsenical books and thank Winterthur Museum for all their research that has led us to this deadly discovery.

Yes, but what did it taste like? 😉

Many of my 19th century ancestors lived and worked in the Mabgate , Burmantofts and New Town areas of East Leeds. A fair number of them are listed in the census returns as ” Dyer”.

It is possible that the emerald green dye was used by them. No telling now if this poisonous dye had an effect on their health. I guess most dyes would have contained noxious substances.

I fully recognise

the contribution of the Gott family both to the Library and Leeds in general ,but the wealth of the city and the nation was won by the thousands of Leeds folk who grafted in dangerous and dirty industries.