This week we welcome Library and Digital Assistant Heather Edwards, who has written a fascinating article on a pioneer of medical history for LGBT+ History Month, told using books in the collections at our Central Library.

To say that medical history and the LGBT+ community have a long, harmonious, and uncomplicated relationship would be a blatant lie. The fact that the medical field has often been used as a persecutory tool against the community, makes the history of it, at best, a minefield. What is rarely highlighted are the contributions of LGBT+ people to the field of medicine and healthcare; The 2024 theme of LGBT+ History Month ‘Under the Scope’ celebrates these contributions throughout history and today. Taking a page out of their book (first library pun, check!). I’ll be showcasing some of our books that highlight these incredible people, their lives, and their work.

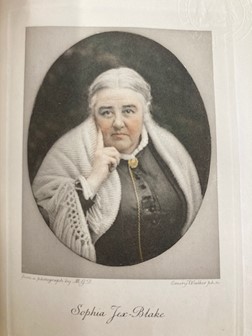

Dr Sophia Jex-Blake

It might surprise you to know, there was once a time of inequality in the workplace. This particular workplace being surgeries, GP’s, pharmacies… This inequality being women barred from attaining any official medical education in the UK.

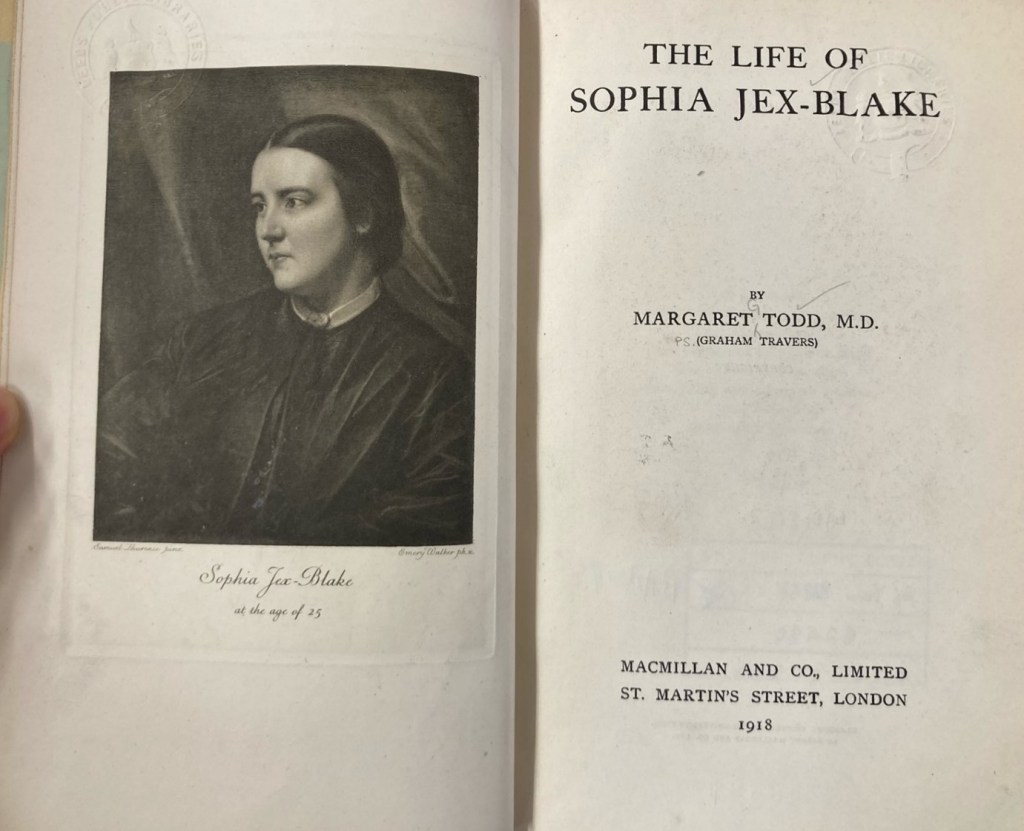

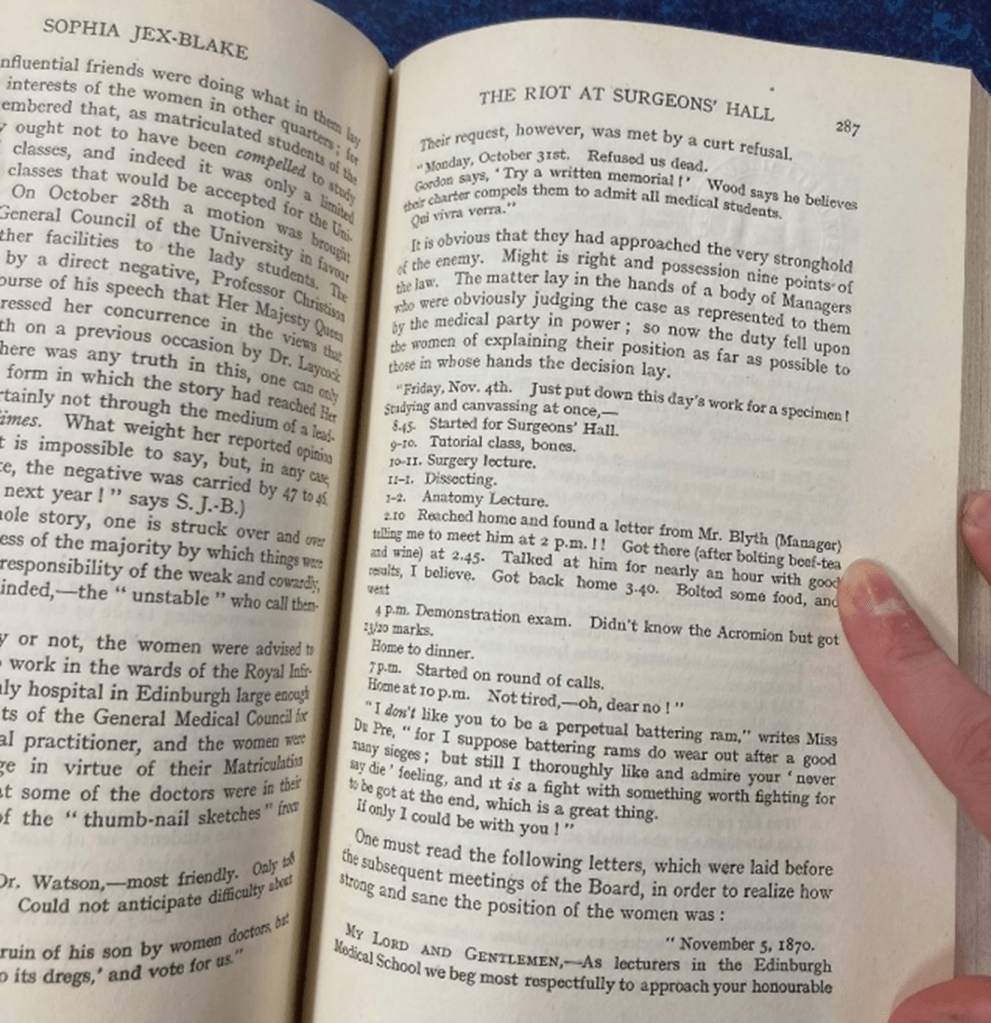

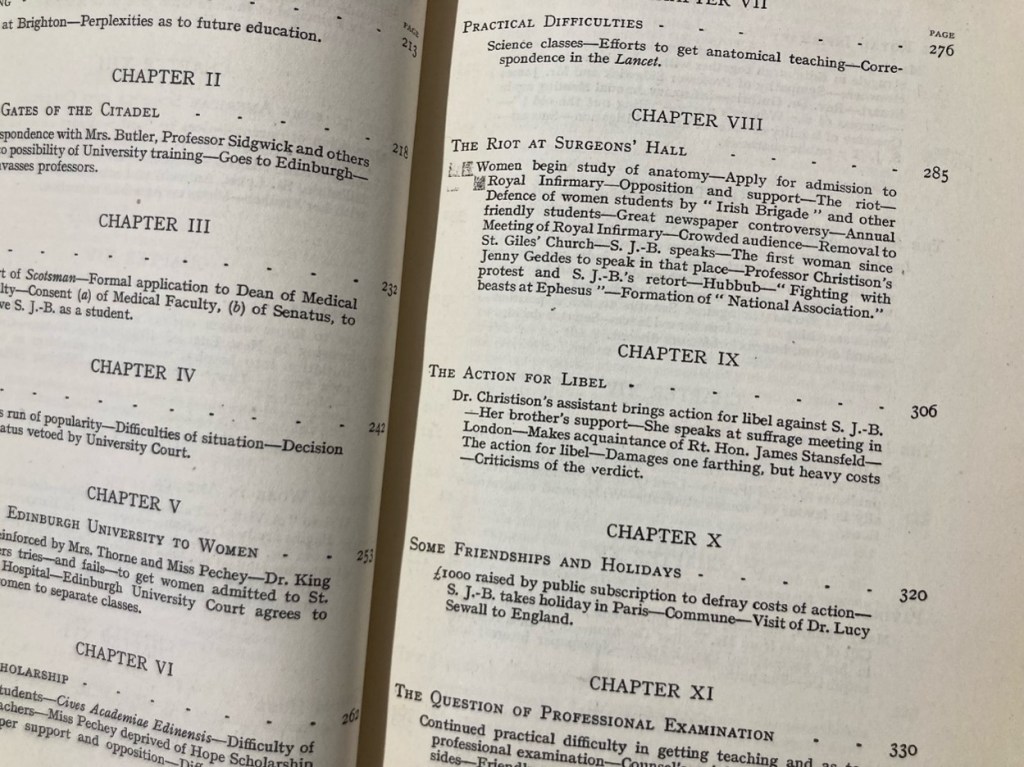

Our first book is the 1918 First-edition biography of Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912); first practicing female doctor in Scotland, third in the wider UK, and a campaign leader for women’s higher education. Written after her death by life-partner and fellow doctor Margaret Todd, MD, it chronicles Jex-Blake’s life using personal letters, diary entries and notations bequeathed to Todd. Interestingly, Jex-Blake herself appears to be a great chronicler, keeping record of everything that might possibly be of use to her future legacy pretty much from the word ‘go’. Or was a major hoarder. Either way, you can sense from childhood she craved a future for herself outside of the expectations of her time.

After attending various private schools, and against her parents’ wishes, she enrolled to Queens College London, before being offered a position as Mathematics tutor while she was still a student. Jex-Blake worked at the college without pay because her family baulked at the idea of her earning a wage; her father subsequently refused her permission to earn a salary. Moving to America in 1865 to learn more about women’s education, Jex-Blake became strongly influenced by her experiences with co-education developments and working as an assistant at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. American pioneer female physician Dr Lucy Ellen Sewall became an important friend for life.

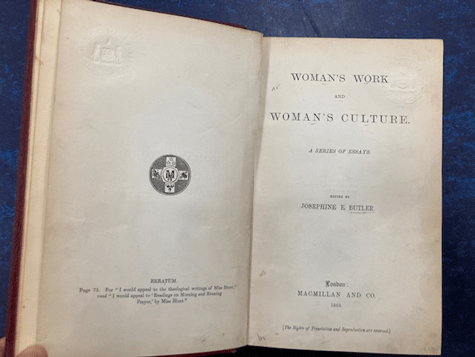

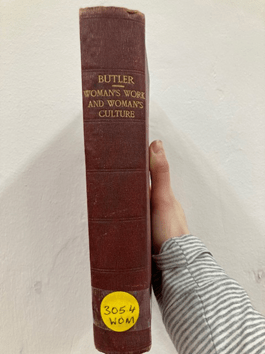

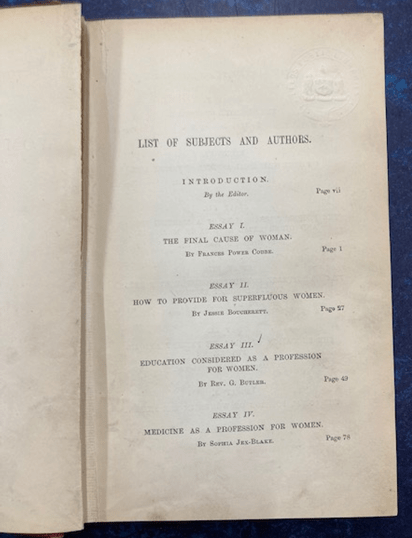

When back in England, Jex-Blake contributed her 1869 essay ‘Medicine as a profession for women’ to a book edited by social reformer and Victorian feminist Josephine Butler, titled ‘Woman’s Work and Women’s Culture’. In her 41-page essay, Jex-Blake argued that there was no objective proof of men being more intelligent than women, and that by teaching and examining women the same as men, such matters could be settled in granting women ‘a fair field and no favour’. She wrote that men had an unfair edge, due to the focus on domestic skills and crafts for women, meaning few could qualify to compete with men in the academic-dominated medicine.

We actually have a first-edition copy of this 1869 reformers collection, so you can come in and read her words for yourself! Other authors include Frances Power Cobbe, Jessie Boucherett, George Butler, James Stuart, Charles H Pearson, Herbert N. Mozley, Julia Wedgwood, Elizabeth C. Wolstenholme, and John-Boyd-Kinnear. It’s worth noting while completing her years at Queens College London, Sophia Jex-Blake lived with another famous social-reformer; co-creator of The National Trust, Octavia Hill. It seems Jex-Blake often ran with a well-known proto-feminist crowd!

Dairy entries included in Jex-Blakes biography have lead historians to speculate about the nature of the intimate friendships hinted at within such social circles, further fuled by her desire not to marry. The following extract describing a trip with Octavia Hill comes from one such entry included in the book:

‘The hurried tea, the night mail, the parting hand pressure as the train moved, ‘in the sure and certain hope’—is it blasphemous so to use the words? I think not. There was a glorious churchlike solemnity always on our love. Well!—then the five months’ parting,—hard it seemed then, but painless—heaven—to what came after. Perhaps I am not yet meant to see the ‘why’ of all that followed…. We seemed so helpful heavenwards to each other. Never seemed our love truer, deeper, purer, I know though now that mine could be all three.’

Hill and Jex-Blake fell out and parted, but it has been widely agreed that Jex-Blake’s romantic partners were women. Todd herself was not included in the biography she wrote, which is interesting. Perhaps somethings were just too intimate to share during that era. Jex-Blake instructed Todd to burn all her private papers, which she did after writing the book.

In 1869, Jex-Blake applied to study medicine at The University of Edinburgh and was rejected. Despite the medical faculty and the senatus academus voting in her favour, the university court rejected her application on the grounds that the university could not make the necessary arrangements “in the interest of one lady”. Said Lady did not take this lying down, beginning a campaign through advertisements in The Scotsman for other women to join her. A secondary application for six more women was submitted and accepted in 1869- making the Edinburgh Seven the first women admitted to study at a British University. Other than Jex-Blake, members of the Seven were: Mary Anderson, Emily Bovell, Matilda Chaplin, Helen Evans, Edith Pechey, and Isabel Thorne. Yet again, Jex-Blake was in good company.

Predictably, as the women demonstrated they could meet male peers on ‘fair field’ hostilities towards them grew. The Edinburgh Seven were harassed with letters, being followed home, hit with mud, and had a firework attached to their door. Once a live sheep was even set loose in the hall, which I’m sure is much less funny when you’re in the middle of your exam. This culminated in the Surgeons’ Hall riot on 18 November 1870, when the women arrived for an anatomy exam, a mob of over 200 gathered outside, hurling mud, rubbish, and insults. It made national headlines at the time and won the Seven new supporters (like Charles Darwin), though this didn’t stop members of the medical faculty persuading the University to refuse them graduation. The courts ruled that the women should never have been allowed entrance, and had their degrees withdrawn. Many of the Seven went to complete their studies at European Universities who allowed women to graduate. Jex-Blake received her medical doctorate from the University of Burne, Switzerland in 1877.

Though the Jex-Blake’s campaign in Edinburgh technically failed, it held the seeds of progress that paved the way for further protests and discussions, eventually leading to (some) women being admitted onto degree programs at other British universities in 1877. Her pioneering spirit has been highlighted by the events and personal documents included in her 1918 biography. Her legacy rerouting around societal hurdles, such as helping found and support various medical schools for women, as well continually championing the cause of women’s education, led to changes in legislation which permitted medical authorities to licence all qualified applicants regardless of gender.

She continued to hold the concerns of women’s health as a core value, setting up a clinic for poor women where they could get quality treatment on the cheap. The clinic was later expanded to include wards and transformed from a small outpatient clinic to Edinburgh Hospital and Dispensary for Women- Scotland’s first hospital for women staffed totally by women.

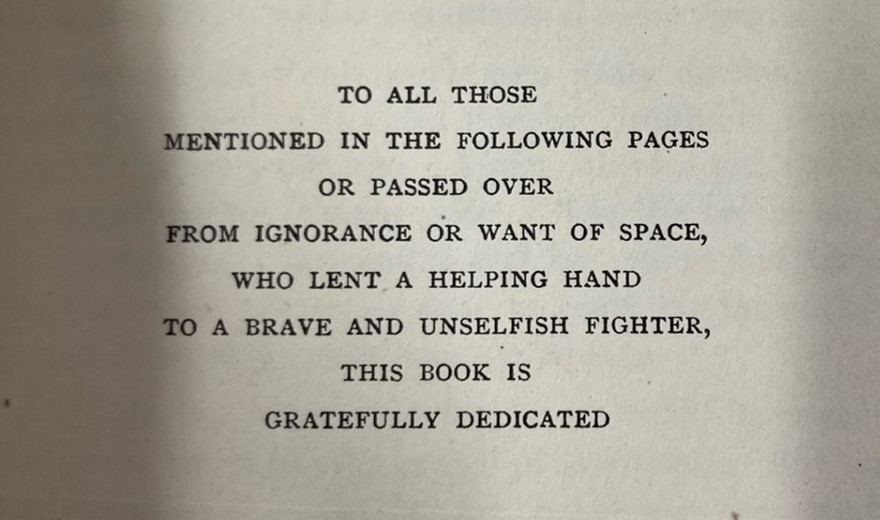

That’s the thing that strikes me most about this book- by a woman, about a woman, and I’d argue largely for women, to show what could be achieved. (Remember that before 1918, no women could vote and it wasn’t until 1928 that women had voting equality with men). Both the subject and author highlights the breadth and importance of relationships with women- be that mentor, family, friends, students, campaigners… the takeaway is that it takes a village, perfectly summarised in the dedication by the author Dr Margaret Todd:

Dr Margaret Todd coined the term ‘isotope’ and was one of Sophia Jex-Blakes first students at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women. After Jex-Blake’s retirement, the two moved together to a cottage in Rotherfield, in what could be seen as a ‘Boston Marriage’. As well as being a practicing doctor, Todd publishing novels based on a female medical student under the name ‘Graham Travers’. Her biography of Sophia Jex-Blake was the first time she didn’t write under a male pseudonym. She died 3 months after the publishing, likely by suicide.

We’re celebrating the 10th-anniversary of the Secret Library Leeds blog this month and over the last decade we’ve published a range of interesting LGBT+ content, mostly based on books and other stock found at our Central Library. Here’s a sample of those articles, but you can find more at this link.

LGBT History Month and Goodbye Olympics

A look at an 18th-century edition of Voltaire’s History of the Russian Empire under Peter the Great: Vol. 1

LGBT+ Leeds: A Brief History in Photographs

Photograph gallery curated by Ross Horsley, then of the West Yorkshire Queer Stories project

An LGBT-themed lucky dip

Brief selections from the collections at the Central Library, including several local history-related items

Male Homosexuality in Britain, 1954 – 1970: The Leeds Link

Exploration of male homosexual life in Leeds after the Second World War, by John-Pierre Joyce, author of Odd Men Out: Male Homosexuality in Britain from Wolfenden to Gay Liberation, 1954-1970

The Leeds Women Against the Clause March

The story of two thousand Leeds people marching against Clause 28 (Section 28) during the Stop the Clause Demonstration on the 5th of March, 1988. The March was organised by Leeds Women against the Clause

LGBT+ Leeds Research Guide

Research guide listing relevant items of stock in the Local and Family History Library.

Surviving Censorship: Patricia Highsmith

An exploration of the life and work of author Patricia Highsmith.

Very good. No doubt you are aware that Edinburgh University awarded honorary MB ChB degrees to the Seven. It took them long enough – but then it is Edinburgh!