We welcome back Library and Digital Assistant Heather Edwards for a sequel to a recent article looking at LGBT+ pioneers in the medical field….Look out for part 3 coming later this week as well.

Way back in LGBT+ History Month, after looking at Dr Sophia Jex-Blake (first practicing female doctor in Scotland and a pioneer of medical education for women) it’s safe to say I went down a bit of a research rabbit hole. And kept tunnelling. I couldn’t believe that I’d never been taught about these icons and was too excited about filling the gap in to stop at Jex-Blake! So, as part of Pride month, in this post we’ll continue having a gander at some of our resources and loanable stock relating to more amazing LGBT+ persons who’ve contributed to the medical and healthcare fields.

Dr Cecil Belfield Clarke

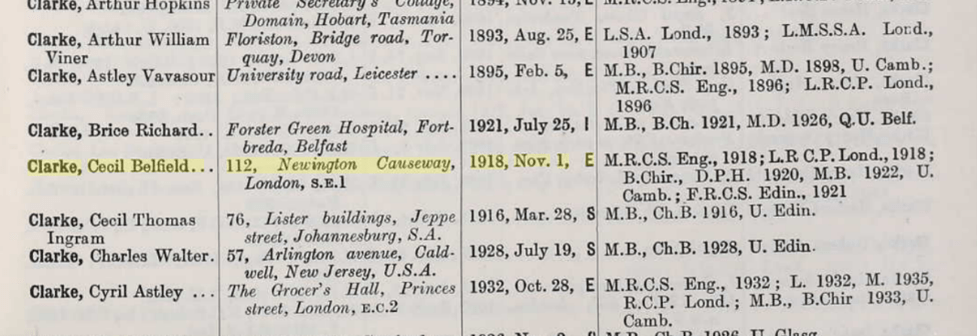

First up we have Dr Cecil Belfield Clarke. Born in 1894 in Barbados, Clarke won an island scholarship to study medicine at Cambridge. He arrived in London just after the outbreak of World War I, travelling on RMS Tagus, which has the great symmetry of later being used as a hospital ship. Studying medicine at St Catherines College, Cambridge, Clarke was awarded his BA degree in 1917. Between 1918-21, he went on to achieve 5 other medical qualifications, and set up his practice near Elephant and Castle. He would work from here for the rest of his career. He continued practicing there throughout the Blitz of WWII, determined to continue caring for his patients despite one side of his practice literally being open to the elements after bombing.

Clarke was a member of the Council of the British Medical Association and developed the ‘Clarke’s Rule’ formula that we still use today to calculate the dosage of medicine given to children. His old college still gives an award in his name. As well as being a brilliant doctor, Clarke was an established Pan-African and Civil Rights activist, best known as a founder of The League of Coloured Peoples and was friends with many famous activists on both sides of the Atlantic. He lived with his partner of 30 years Edward ‘Pat’ Walker. Although being ‘out’ to close friends and activist colleagues, the couple had to be discreet because homosexuality wasn’t decriminalised until 1967 (Yes, that depressingly recently).

You can find out more about Dr Cecil Belfield Clarke and the organisations he was a part of in:

Or by going through Leeds Libraries on Ancestry.co.uk to view more records of his arrival, practice, and partner Pat.

Dr Flora Murray & Dr Louisa Garrett Anderson

The definition of a power couple, Dr’s Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson were medical pioneers who set up multiple hospitals and militant Suffragettes who fulfilled both leadership and supporting roles in the movement.

Louisa Garret Anderson (1873-1943) was born into a family of Suffragists and medical women, but that hasn’t stopped her distinguishing herself in her own right. Her mother, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson became the first qualified British female physician by finding a loophole in admissions at the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries and was admitted to the Society of Apothecaries where she took her exam in 1965. Of those who took this exam, she was the only woman, and scored the highest marks. The society then changed the rules to prevent other women obtaining their licence, thereby inadvertently becoming part of the reason Sophia Jex-Blake couldn’t achieve her credentials until 1876 (you know, other than the patriarchy!) This also affected Louisa, who after attending The London School of Medicine for Women (that her mother and Jex-Blake founded) found it difficult to gain a position in a general hospital. She joined The New Hospital for Women in 1902, rising from surgical assistant to senior surgeon and performing general and gynaecological operations.

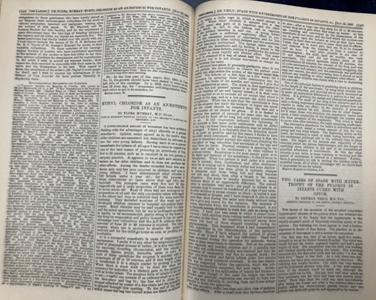

Flora Murray also studied at The London School of Medicine for Women. After this she went on to further her studies and worked in an asylum, as a medical officer at the Belgrave Hospital for Children, and as an anaesthetist at the Chelsea Hospital for Women. In 1905, such experiences lead her to publishing her article on anaesthetic in Children in The Lancet, one of the world’s leading medical journals at the time. Having gone routing around in our backrooms to find it, you can now come and read her full article at Central Library.

In 1912 Murray and Garrett Anderson founded the Women and Children’s Hospital, which provided working class children with healthcare. This was the start of a long running partnership, starting the Women’s Hospital Corps after the outbreak of WW1 and recruiting women to staff it. Unsurprisingly given the history of rampant sexism in medical and political fields, Murray and Garrett Anderson felt that the British War Office would reject their assistance, whereas the French Red Cross were in dire need of it. They were provided with an area of newly-built hotel in Paris, and with Murray as chief physician, and Garrett Anderson as chief Surgeon, the hospital was such a success that others followed in Wimereux and back in London at Endall Street. It was here that Garret Anderson co-implemented a new method of treating septic wounds called BIPP. We have the original article on their findings in our 1917 edition of The Lancet; come and read the medical trial that pioneered how we treat wounds today. If you’re a lover of charts and numbers, this’ll do it for you!

Murray and Garrett Anderson were both militant Suffragettes, campaigning and offering their services in a medical capacity. Louisa was one of the over 100 women arrested on Black Friday and was also imprisoned in Holloway in 1912 for her suffragist activities (including bricking a window). Flora was a member of the 1911 Census Protest, nursed suffragette hunger-strikers such as Emmeline Pankhurst after their imprisonment, and campaigned against the force feeding of prisoners. It’s clear that this couple cared deeply about caring for and protecting others, including each other. After retirement, they lived in a cottage until Flora’s death, and were memorialised together on Murray’s tombstone, and her book dedication; “To Louisa Garrett Anderson / Bold, cautious, true and my loving companion.”

You can read more about Dr Murray, Dr Garrett Anderson, and the host of suffragists and women doctors they surrounded themselves with in:

All the books and other resources referenced in this article are available from Leeds Libraries. Please contact our Library Enquiries department for further information on access requirements: leeds.libraries@leeds.gov.uk or 0113 37 85005

Excellent post. Well done!!