- by Antony Ramm, Leeds Central Library

This is an entry in our Read More series. These are ‘long-form’ articles, where staff offer a curated and detailed look at areas of our book collections, usually based around a specific theme or subject. These posts aim to guide the interested reader through to those books that offer a more in-depth look at a topic, or which are classics in their field.

As most people know, the 5th of November commemorates the prevention of an attack on King James I and Parliament in 1605. And most people know the broad outline of that “Gunpowder Treason Plot”: a group of conspirators; gunpowder in the House of Lords (guarded by Guy Fawkes); and, perhaps, a faint recollection that the events had something to do with Catholic grievances against the State. For the most part that is all the knowledge anyone needs: Bonfire Night – like most cultural rituals – has evolved over time into a more general community activity; an event that persists because of a continuing need for social experience, rather than because of any continuing stake in the arguments on either side of the original debate.

But that is not to say further exploration of the Plot itself is a waste of anyone’s time. Quite the opposite: in its tangling of (perceived) State oppression and a planned terrorist ‘spectacle’; the ‘deep politics’ of espionage and counter-espionage; intercepted communications and torture – we can see an affair with curiously modern parallels.

Similar contemporary parallels have not been lost on earlier observers. Mary Whitmore Jones, in her The Gunpowder Plot and Life of Robert Catesby (Catesby being the lead conspirator) – available, as are all the titles mentioned in this blog, from our Information and Research stock – draws a comparison with the events of 1605 and those of the early 20th-century: “In these days of Anarchist plots…[i]t be may be interesting to recall the story of the greatest projected crime in English history, the Gunpowder Plot”. Other titles that provide a narrative of events include Gunpowder, Treason and Plot (Lewis Winstock) – an excellent short, illustrated, introduction – and C.Northcote Parkinson’s similarly-titled work.

A glance through the Gunpowder Plot literature is also a reminder that, as well as those who uphold the ‘official’ narrative, every conspiracy attracts its share of conspiracy theorists. Such debates have raged among observers of the Gunpowder Plot ever since an Italian diplomat wrote, in 1605, “[t]hose that have practical experience of the way in which things are done hold it as certain that there has been foul play and that some of the [Privy] Council secretly spun a web to entangle these poor gentlemen.” The introduction to Hugh Ross Williamson’s The Gunpowder Plot lays out a fascinating account of the differing positions taken by historians over the centuries. Titles mentioned by Williamson that are available to read in the Local and Family History library include A Narrative of the Gunpowder Plot (David Jardine); John Gerard’s What Was the Gunpowder Plot?; and Samuel Rawson Gardiner’s What the Gunpowder Plot Was.

Gardiner’s book was a response to Gerard’s accusation that Robert Cecil, the first Earl of Salisbury, and the spymaster for King James I, had manipulated the conspirators as a means to discredit the cause of Catholic recusants. Cecil – one of the most intriguing figures in all of English history – has his life and career covered in two biographical studies . The wider historical context is explored in such titles as The Early Stuarts: 1603-1660 (Godfrey Davis), while Whitsun Riot: An Account of a Commotion Amongst Catholics in Herefordshire and Monmouthshire in 1605 (Roland Mathias) is a fascinating look at another Catholic ‘plot’ in the same year as Catesby’s doomed effort.

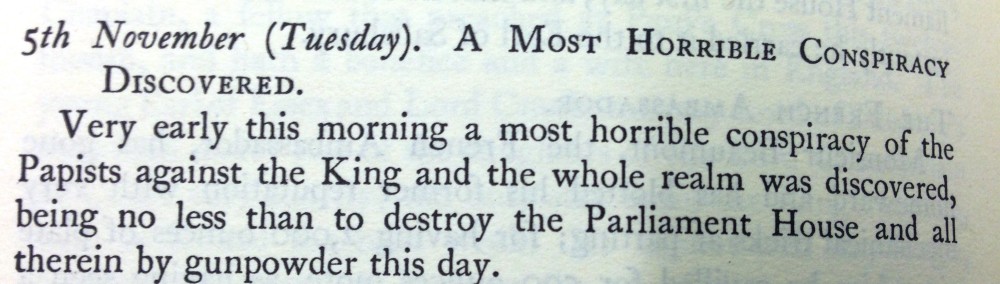

Those conspiracy theories mentioned above have their roots in the various inconsistences and omissions in the official record. Anyone wishing to explore for themselves the murky details of the plotting, the capturing and, finally, the trial of the conspirators, would be well advised to spend some time with the primary sources on which historians’ accounts have been based. One place to start would be A Jacobean Journal: Being a Record of Those Things Most Talked of During the Years 1603-1606, which gives a modern reader a sense of how contemporaries reacted to the events as they unfolded (extract below).

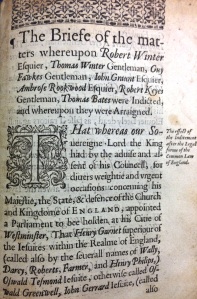

Most importantly, however, the Information and Research library also holds a copy of the 1606 title A true and perfect relation of the proceedings at the seuerall (sic) arraignments of the late most barbarous traitors – that is, the text of the plotters’ trial as it occurred.

This fascinating contemporary document, as close as most modern readers will get to being in the room with the conspirators at their interrogation, is – strangely – bound together with a book from 1614 entitled Titles of Honour by the jurist and legal scholar John Selden. While Selden’s work remains a key early text in the field of peerage law, there seems no clear reason why these two titles have been collected together; if any library users know the answer, please let us know!

2 Comments Add yours