Alice Mann (1791-1865)

Central Street and Duncan Street

This Leeds-born radical and publisher operated primarily from a bookshop based in the now-demolished Central Market on Duncan Street (near to Central Street). Alice married James Mann, a prominent West Riding political activist and bookseller, in 1807. After his death she took on his business to support her family. She continued James’ philosophy, publishing work by influential radicals such as Richard Carlile, Richard Oastler and William Rider and numbered many local Chartists among her clientele. Her political commitment is evidenced by her prosecution in 1834 and 1836 for selling unstamped newspapers. Alice balanced this activity with more mainstream printing, including canvassing for contracts from the Town Corporation. Her business was continued by her sons following her death in 1865.

As a New Zealand-bound fan of the Local and Family History collection, I naturally consulted the two relevant chapters of their copy of Mann’s Emigrant’s Guide (published 1850) prior to my trip. Given the vexation and labour I have caused myself I am now not sure it was a wise choice.

On the one hand Mann’s Emigrant’s Guide was quite useful. As correctly promised “No traveller has ever visited New Zealand, who has not been delighted and spoken in the highest terms of its delightful climate.” (p.23) “ that they [the people] are a fine race … perhaps the finest … quiet, peaceable, and disposed to be industrious” (p.28) Neither was I troubled by “The only drawback as regards the local peculiarities is the occasional earthquake , the subterranean heats not having exhausted themselves” (p.26)

But on the other has the book itself raises some troubling questions. It is easy to admire the book’s probable author, Alice Mann. The younger, Leeds-born Alice played a significant role in both the Luddite and Chartist social justice movements. By the middle age, however, Alice seems to be expressing imperialist, colonising views that are the antithesis of social justice.

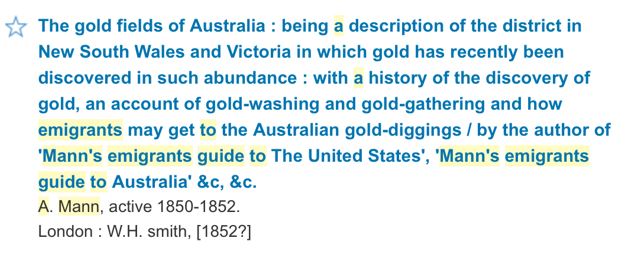

There is no named author anywhere in the whole text. Alice Mann (1791- 1865) was a Leeds bookseller, printer and publisher, who definitely printed it. She may well also be the author. The British Library does not have a copy of the Emigrant’s Guide, but they do catalogue a companion volume, and appear happy to attribute authorship to one ‘A. Mann’ for the Emigrant’s Guide.

There are couple of authorship red herrings though to confuse the reader. The first title page of the Local and Family History library’s copy of the Emigrant’s Guide has a very faint, manuscript ‘Mann’. At first sight a definitive clue; maybe even a signed first edition? But it is more likely that the manuscript ‘Mann’ was made by a later hand – possibly one of the library staff – in collating what were originally three, rather distressed pamphlets for dispatch to the binders.

Then there is the question of possible authorship by Robert James Mann (1816 – 1886), a Norwich-born physician, who in later life became a prolific non-fiction author and wrote The Emigrant’s Guide to Natal in 1868 (ONDB). But there is no evidence of any link to the family of Leeds-born James Mann, whom Alice had married in 1807. No reason, then, to place much faith in Alice enlisting the help of a distant relative by marriage in compiling the 1850 text. Especially since R.J. Mann was still working as a physician in Lincoln at the time.

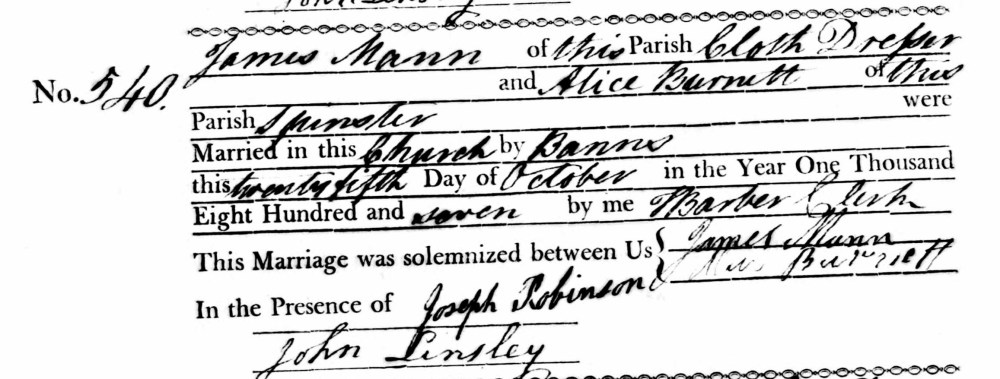

There is no doubt that Alice Mann, “a woman of indomitable energy, steely principle and entrepreneurial flair “(Chase, ONDB) was more than capable of writing the Emigrant’s Guide. As we shall see, she is also credited with being the author/compiler of at least one other. At the age of 16, energetic, principled Alice married James Mann, then a cloth dresser. James Mann was strongly suspected by authorities of being a leading Leeds’ Luddite (Chase, ONDB – see also p.645 in the 1968 edition of E.P. Thompson’s, The Making of the English Working Class). Was the twenty-one year old Alice equally active in the Luddite movement? Shaun Cohen adds a comment to the Leodis photograph of 14-20 Duncan Street “… just off the picture is no. 12, the premises of Alice Mann … it is very likely that Alice led disturbances in Briggate in 1812 and called herself Lady Ludd”. As some corroboration, the Ipswich Journal carried this report of a disturbance in Briggate in late August of 1812:

In the afternoon [in Leeds] a number of women and boys, headed by a female who was dignified with the title of Lady Ludd, paraded the streets, beating up for a mob.

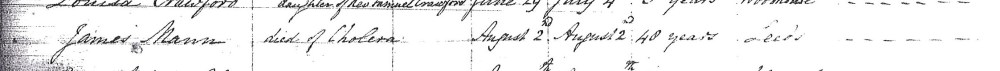

James and Alice took up book-selling in about 1818, with premises in Briggate that, according to the Leeds Intelligencer “appears to be the headquarters of sedition in this town.” (Chase, ONDB). When James died suddenly in 1832, the “ steely principled”, forty- one year old Alice, with seven dependent children, took on the book-selling and, later, printing/ publishing business.

In both 1834 and 1836 Alice served prison sentences for selling unstamped newspapers. At her trial in 1836 she declined to pay a reduced fine and escape prison if she ceased book-selling, saying “…. She had no other mode of maintaining her family” (Chase, ONDB).

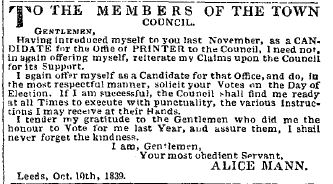

Her book-selling, printing and publishing business expanded, and moved to the newly-built Central Market. She tendered for printing contracts for Leeds local government bodies. She also published very popular local almanacs and, later, more practical texts; including guides for for flax spinners, worsted manufacturers and to The Factory Acts Made Easy. She worked extensively with other Radical printers across the country, including London-based William Strange and, reputedly, the Leeds-based Joshua Hobson. Indeed, Strange is prominently listed as the distributor of the Emigrant’s Guide (Chase, ONDB).

At this time there is additional evidence that she was an author/compiler: “She also printed, jointly published (with Strange), and conceivably herself compiled Mann’s Black Book of British Aristocracy: An Exposure of the More Abuses in the State and Church in 1848 (Chase, ONDB).

The three pamphlets that are bound together to form the Mann’s Emigrant’s Guide first appeared in 1849 and 1850. The two New Zealand chapters read like a compilation rather than reporting personal experience and insight; though that is not to suggest that compiling them was an easy task in itself. In Chapter 1 there are detailed descriptions of New Zealand’s geography, climate and agricultural production, while Chapter 2 has detailed census-like descriptions of the newly-established European settlements. Both chapters probably rely heavily on extracts from the reports of the New Zealand Company, the London-based organisation managing most British emigration in the period between 1840 and 1858. While the journalistic colour comes from Mr. Earle, a missionary, and Mr. Carrington, who extols a climate “… so healthy that you can undergo wettings and great exposure without suffering serious injury” (p.25). Lastly, William Battin’s lengthy letter back to his former employer in Romsey paints a glowing picture of all that awaits the immigrant (p.29-31).

By 1850 immigration to New Zealand from people born in the British Isles was growing quickly, though English-born migrants tended to arrive from the South-East and South-West – especially Cornwall – rather than the North of England. However, from the 1830s Leeds’ readers had been able to regularly follow events in New Zealand. So, on December 21st 1833, there was a Leeds Mercury report on the installation of James Busby as British resident in New Zealand, and the serving of a cold collation to the twenty-two Maori chiefs present. But it was New Zealand flax that ensured a continued interest. The Leeds Mercury carried regular reports of price of New Zealand flax on the London market; especially important since Leeds became “… the principle centre of the British flax industry,” and boasted John Marshall’s splendid, flax-spinning Temple Mill in Water Lane (David Thornton, The Story of Leeds, p.110).

But the Mercury’s readers were also assumed to have loftier interests. On Saturday March 7 1835 the Ilkley Missionary Meeting heard from Mr. Leigh, “late missionary to New Zealand,” (Leeds Mercury), and by January 1838, J. Williams was able to write to the Leeds Mercury reporting the gift of £300 by Earl Fitzwilliam to equip a missionary ship for the Church Mission Society. In just over year, The Times itself was reporting on a dinner held to celebrate the fruition of Fitzwilliam’s gift. The fitting out of the ship Tory “… to proceed to New Zealand and colonise it on behalf of the association recently formed [New Zealand Company].” Jarringly, having first resolved to colonise an already well populated country, the association then “especially forbade any act of aggression or affront to the natives” (The Times. May 11 1839).

The complex results of the interrelated colonial, commercial and spiritual drivers that are still debated in New Zealand today is too big to explore here. But, in essence, when the aforementioned James Busby, British Resident, brought together a substantial number of Maori chiefs in 1840 to sign the Treaty of Waitangi, there was a fatal misunderstanding amongst the signatories of the terms ‘sovereignty’ and ‘governance’.

But, even without the benefits of hindsight, Alice Mann could have been better informed of the impact of European migration on the Maoris. The Times, which had carried advertisements for Alice Mann’s text books, reported at length on a House of Commons debate on the mishandling by the Colonial Office of the New Zealand (The Times, 18.06.1845). Closer to home, the Leeds Mercury reported on a partial settlement of the “much embroiled” relationship between Maori and Europeans, arising from the “ …repeated attempts by certain parties to set aside the Treaty by which these intelligent and warlike [peoples] some years since yielded sovereignty“ (Leeds Mercury, 27.06.1846).

But there was no recognition of any controversy when fifty-year old Alice Mann (potentially) wrote “Our national instinct is to colonise. The character and temperament of our people fit them for the work and wherever they plant their feet the wilderness is made to blossom like a rose. … in all quarters of the globe the British race, the British language and British civilization in its highest form, seem destined by Providence to ultimately prevail.” (Preface, Mann’s Emigrant Guide). Where did the twenty–one year old Alice, possible leader of a Luddite riot, go? What happened to the forty-year old, recently widowed Alice, who served prison terms rather than give up distributing Chartist newspapers?

This article has been written by Tony Scaife, a guest author, and draws on Professor Malcolm Chase’s biographical account of Alice Mann, available free to all Leeds Libraries members, via the link to Oxford Dictionary of National Biography website on our Online Resources page. Please contact the Local and Family History department to access any of the other resources listed in this article.

8 Comments Add yours