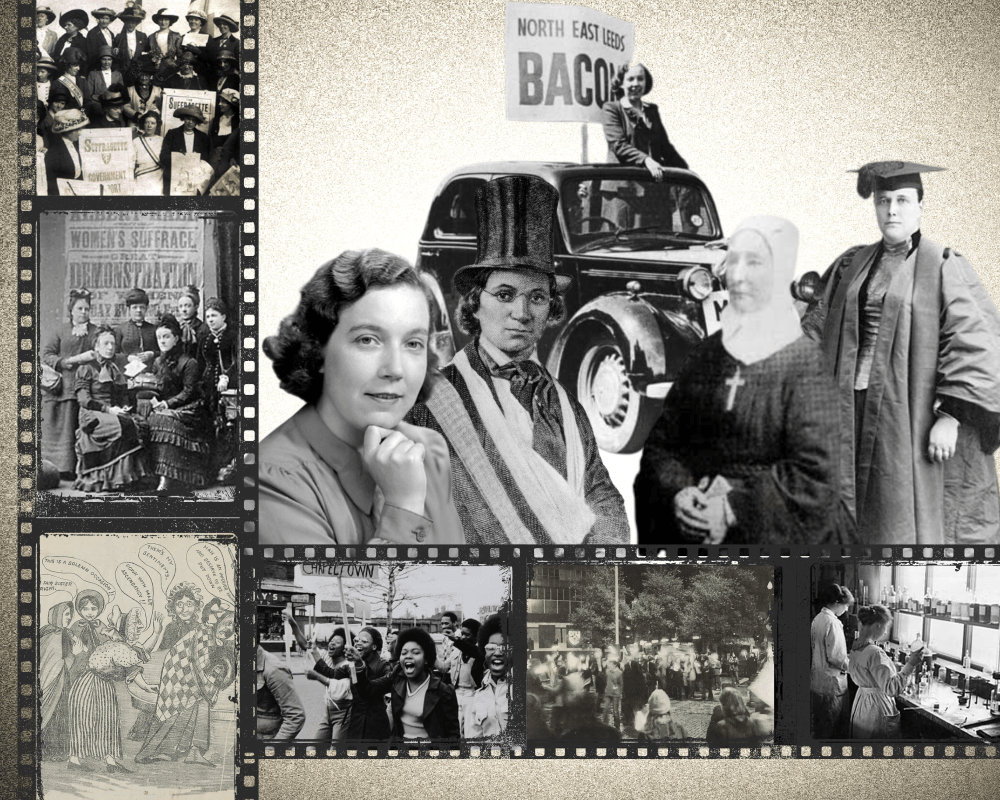

This year to celebrate International Women’s Day, Library and Digital Assistant Alexandra Brummitt takes a closer look at the lives and works of some lesser-known feminist pioneers that lived in Leeds.

International Women’s Day is held on March 8th every year and is a global celebration of the social, economic and political achievements of women. This year the day’s theme is Accelerate Action. At the current rate of progress, it will take until 2158 for women to reach full gender parity, which is roughly five generations from now. The hope with this year’s theme is to speed up this progress worldwide, from campaigning and protesting to raising awareness of the issues facing women today.

To celebrate this theme, I want to share the history of some of the activists who paved the way for women in Leeds. From the suffrage movement to the first female doctors to thousands of women reclaiming the night, women of Leeds have always been trailblazers. I hope that these women’s stories will help to inspire the next generation of women from Leeds to accelerate action!

Sister Agnes Logan Stewart, 1820 – 1886

Born to a wealthy family in London Agnes had a comfortable upbringing. She was always involved in her local church and when she was in her twenties she became a sister of mercy. Not long after this her father died and left her (his only child and next of kin) his fortune. Having no desire to spend the money on herself she decided to use this money to better the lives of those less fortunate than herself.

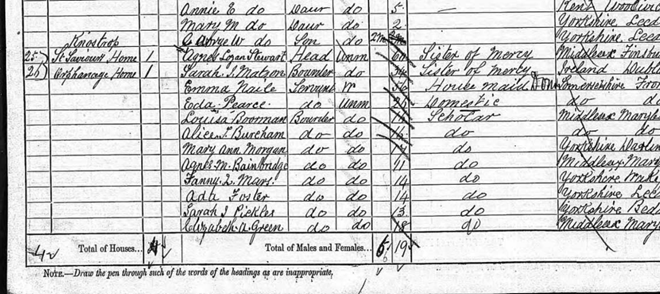

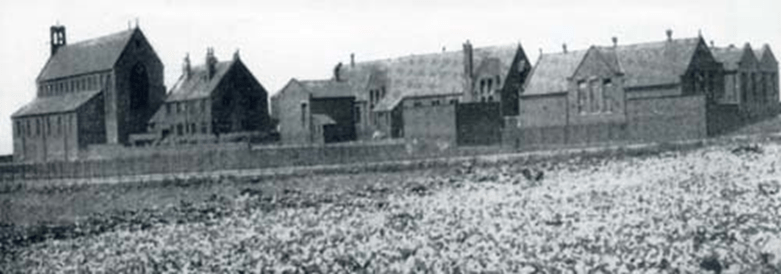

In 1871, she came across a call for a ‘lady of private means’ to help restore the deprived parish of St Saviours in Richmond Hill, Leeds. She wasted no time and one of the first things she did was establish St Saviours Home, an orphanage that had 20 girls, between 5 and 18, living there within a year of her arriving. The orphanage remained there until 1939, and the building was later demolished in 1994.

Her good work did not stop there though. With her money she established a gymnasium for local boys in the area, she set up a youth brass band within the church, she set up a night school for local working-class men to learn to read and write. She had a great passion for education and is responsible for the building of a girls and infants’ school at Cross Green and St Hilda’s school for boys. She would also pay for books for the schools, as well as subsidise the school fees for poorer children in the area. In 1870, the Education Act was passed and was the first step to making education available to all, requiring local authorities to build schools in areas that needed them. In 1880 another act was passed that made schooling compulsory to all children aged 5 to 10 years old.

Sister Agnes would also pay for children of a ‘delicate’ nature to spend a month on the coast taking in the sea air. In this period healthcare was non-existent, and diseases would spread quickly among the working classes. It was a common Victorian belief that sea air, or country air had healing properties and could cure all kinds of ailments. It did have a good success rate, but most likely because they weren’t in crowded and unsanitary conditions.

Sister Agnes’ good deeds carried on even after she died in 1886. She left all her money to the schools that she had founded and to St Saviours home. However now that the schools and the orphanage have been demolished, not much remains of the legacy of Sister Agnes.

Ellen Craft, 1826 – 1891

Ellen Craft was born in Georgia, United States, and was born as an enslaved person. She was given as a gift to work on another estate far away from her mother when she was only 11 years old. It was here where she met her future Husband, William Craft. In 1848, the pair managed to escape, due mainly to Ellen’s pale skin, allowing her to disguise as a white man (women would not have travelled alone with an enslaved man). As well as this, Ellen had been working as a house servant, giving her a good knowledge of the local area. The two managed to get all the way to Boston.

The two got married shortly after escaping and Ellen wore the clothing she escaped in for their photographs. This photograph was published in many anti-slavery and abolitionist publications, making their escape somewhat famous.

They lived in Boston for two years, during this time they made numerous public appearances, speaking publicly about their escape and rallying anti-slavery sentiment. Ellen mainly stood aside while her husband spoke, a woman speaking in front of a large mixed crowd would have been disapproved of. However, audiences began to grow curious of this young woman who had been so brazen in her escape, and she is reported as speaking alone in front of crowds of nearly 1000 people on more than on occasion.

In 1850 the Fugitive Slave Act was passed, making it legal for bounty hunters to capture enslaved people who had escaped, even in free states. No longer safe in Boston, the Crafts bought passage on a steam ferry to Liverpool. William Craft described the moment of landing in England:

“It was not until we stepped ashore at Liverpool that we were free from every slavish fear”.

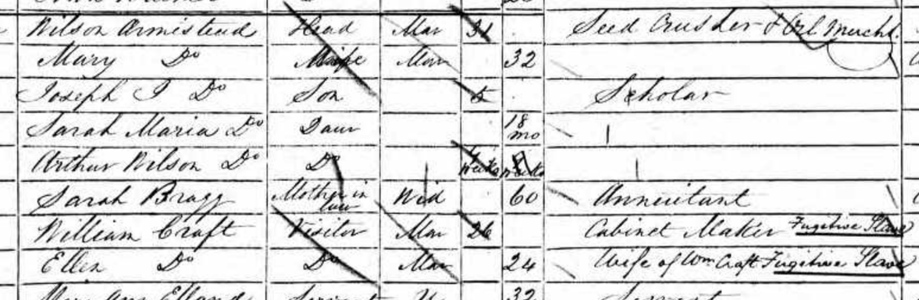

Abolitionist Wilson Armistead took the couple in when they arrived in England, and they were registered as living with him in the 1851 census. Under their professions in the census, Armistead has described the pair as ‘fugitive slaves’, this was commonly done in Britain by abolitionists to protest the unjust laws in the United States.

While in Leeds, Ellen learnt to read and write, something that as an enslaved person would have been beaten for. She continued to give lectures and public speeches, as well as writing articles for abolitionist publications.

The Crafts’ moved from Leeds after a few years and bought a house in London, which became a hub for activism in the area. They supported many causes, including the suffrage movement, and they would regularly have other abolitionists and suffrage fighters stay with them. Eventually they saved up enough money to rescue Ellen’s mother from enslavement, and she spent the rest of her life living with her daughter as a free woman.

In 1860 the couple released their biography, Running a Thousand Miles to Freedom, which was extremely successful. It is safe to say that Ellen accelerated action in her time.

Dr Edith Pechey, 1845 – 1908

In 1869, Edith Pechey joined four other women trying to train as doctors at Edinburgh School of Medicine. These were the first women to ever be trained as doctors, and despite being let in the door they did not have an easy time of it. The women were taught separately to the men and were charged a significant amount more for this education. They also faced immense push back from their fellow male students, who believed they did not belong in the school. They had insults shouted at them in the hallways and on a few occasions, people even threw rocks at them, trying to get them to quit.

Despite all the troubles she faced at the university, Pechey did not back down. She worked hard and received some of the best grades in her year (the men included). The university, after all the backlash that had been received, decided after the women had completed their studies that they would not get their degrees. Understandably angry, but determined as ever, the women all decided to look to other universities to award them their MDs.

Pechey was awarded her MD by the university of Berne in Switzerland in 1877. This meant that not only did she pass her exams at two universities, but she passed them after sitting them in German which was not her native language. After she had gained her doctorate Pechey came to Leeds and began practicing medicine in Park Square.

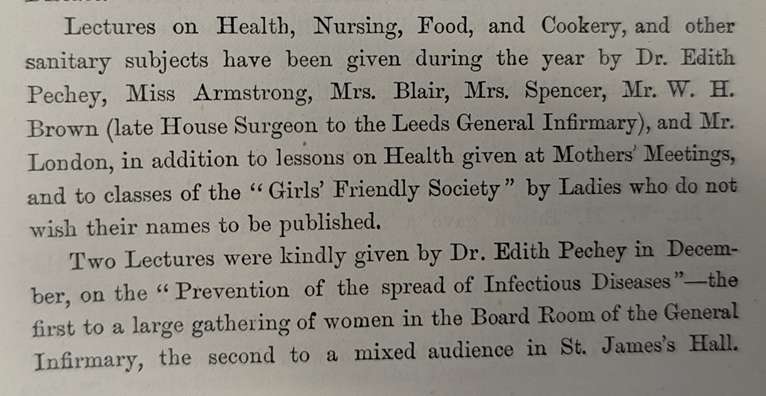

During her time in Leeds, Pechey made somewhat of an impact. She believed strongly in educating the working classes in order to improve their standard of health and was involved in the Leeds Public Dispensary, a free hospital for women and children in the city. She was also actively involved with the ‘Yorkshire Ladies Council of Education’, whose objectives included:

“The improvement of girls and women from the industrial classes … by lessons and lectures on health.”

In the 1882 annual report for the Ladies Council, Pechey is listed as being among the lecturers for their health department. In that year she gave two speeches to large audiences, one of exclusively women, about prevention of infectious diseases.

In the same year, tired of the way female doctors were being treated, Pechey established the Medical Women’s Federation of England, and was voted President. This organisation is still thriving and according to their website is the ‘largest organisation of women doctors and medical students in the UK’.

In 1883, she received an invitation to work in India from George Kittredge, an American businessman who had started a group to help women in India get better access to healthcare. The laws in India at the time said that male doctors were unable to treat women, so the country was in desperate need of women doctors. In Bombay she spent over 20 years working tirelessly for women’s healthcare. She established a training school for nurses, she gave lectures to women and girls about various health problems, she helped manage an outbreak of bubonic plague and cholera in the city and she sponsored the education of Rukhmabai, who was the first woman in India to practice medicine.

In 1905, Pechey returned to Leeds due to declining health conditions. However, this did not deter her from continuing to fight for women’s rights. In 1907 she marched in the famous Mud March, a peaceful protest organised by the suffragists. Unfortunately, she never got to see women gain the right to vote as she died from breast cancer in 1908. To honour her, her husband established a scholarship at the London School of Medicine to help women train to become doctors. She continued to help women in medicine until 1948.

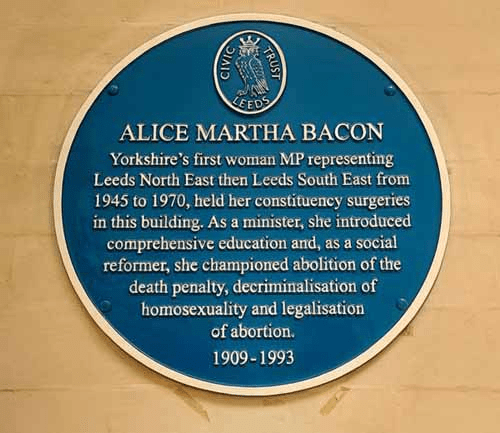

Baroness Alice Bacon, 1909 – 1993

Alice Bacon was born to a working-class mining family in Normanton. Despite modest beginnings Bacon worked hard, getting accepted to a grammar school and then a teacher training college before becoming a teacher. Bacon’s father was the secretary for his branch of the National Union of coal miners, so it is no surprise that she was always politically minded and was dedicated to better the lives of working-class people.

At just 16 years old Bacon delivered her first speech at a Labour Party meeting. She was also very active in the National Union of Teachers, a trade union dedicated to improving working conditions for teachers, she even became the president of the West Yorkshire division in 1944.

Still wanting to do more to improve society, in 1945 she stood for election as the member of parliament for Leeds North East. When she was elected, she became the first female MP elected in Leeds, another female MP would not be elected in Leeds until 2010 when Rachel Reeves was elected. In this election, only 15 women were elected as MPs out of a total of 630 seats in the House of Commons.

In modern day politics, you expect your MP to stand for the concerns of your constituency. However, in post war politics, this would not always be the case. As an example, Duncan Sandys, who was the MP for Streatham and Norwood (and the son-in-law of Winston Churchill) was reportedly only seen in his constituency in the lead up to re-election. Bacon refused to be this kind of politician, never forgetting her roots or the working-class public that she was representing in the House of Commons. She would host regular local surgeries to talk to her constituents and find out what the main concerns of the city were. Upon her death in 1993, the Yorkshire Evening Post fondly remembered her, quoting:

“[She] was able to deal with world leaders and Leeds pensioners in the same honest, forthright manner.“

Bacon was an avid supporter of social reform and constantly campaigned for housing, education, working conditions and several other progressive reforms. In 1964 she became part of the Labour cabinet, as a minister of state for the Home Office. While in this role she helped oversee several major reforms. The first was the Murder Act of 1965, which essentially abolished the death penalty in the UK. In 1967 both the Sexual Offences Act and the Abortion Act were passed, legalising both homosexuality and abortion.

However, her main platform was free and inclusive education. She believed that the many working-class children were being unfairly penalised by the 11 plus, an exam that children would take at 11 years old to determine if they were ‘smart enough’ to attend the elite grammar schools. Both her and the Harold Wilson government campaigned heavily for grammar schools and secondary schools to merge and become comprehensive schools, with the hopes of providing equal opportunities to all children, regardless of class background. In 1965 the government released a circular, urging Local Education Authorities to convert their secondary schools into comprehensive schools. By 1967 Bacon had been moved to the Department of Education and worked tirelessly to make comprehensive schools the standard.

In 1970 Labour lost the general election and was replaced by what would be Margret Thatcher’s Conservative party. Thatcher was openly against comprehensive education, however, her government built more comprehensive schools than any other government. This was due to the amount of work Alice Bacon did in the Department for Education, meaning in 1970 her plans for comprehensive education were too far ahead that it would have cost more to have stopped the works.

Bacon retired in 1970 and was awarded a seat in the House of Commons, where she continued to fight for the rights of working-class people in Leeds, and across the country, until she died in 1993.

*****

It would be impossible to put all the inspirational women from Leeds into one blog post, it may be hard to fit them into a book. If you want to know about more of the women from Leeds, then why not have a look at these other blog posts?

I don’t see the barriers in the same way nowadays. There are few barriers to doing what job you want to do or to educate yourself as you see fit. Obviously people will claim you are not suitable for the role but that happens to men as well (myself included). I would say do what you are comfortable with, with the proviso of meeting basic needs in some way. Obviously if all you aspire to in life is being a manicurist or coffee shop owner, then that has it’s limits of viability for a functioning society so I would urge being a little more adventurous.